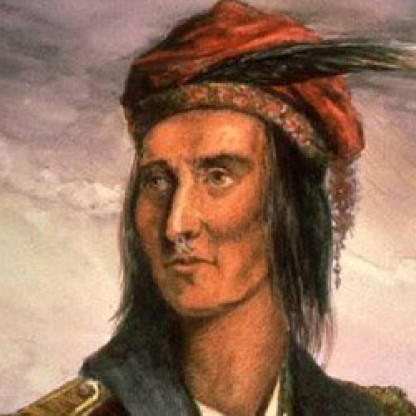

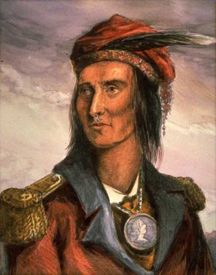

Tecumseh (in Shawnee, Tekoomsē, meaning "Shooting Star" or "Panther Across The Sky", or "Blazing Comet," and also written as Tecumtha or Tekamthi) was born in March 1768. Some accounts identify his birthplace as Old Chillicothe (the present-day Oldtown area of Xenia Township, Greene County, Ohio, about 12 miles (19 km) east of Dayton). Because the Shawnee did not settle in Old Chillicothe until 1774, biographer John Sugden concludes that Tecumseh was born either in a different village named "Chillicothe" (in Shawnee, Chalahgawtha) along the Scioto River, near present-day Chillicothe, Ohio, or in a nearby Kispoko village situated along a small tributary of the Scioto. (Tecumseh's family had moved to this village around the time of his birth.)