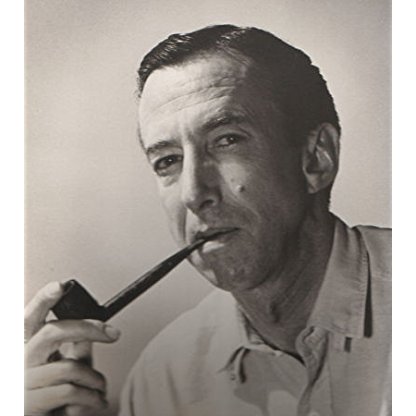

Buckley was born November 24, 1925, in New York City, the son of Aloise Josephine Antonia (Steiner) and william Frank Buckley Sr., a Texas-born Lawyer and oil developer. His mother, from New Orleans, was of Swiss-German, German, and Irish descent, while his paternal grandparents, from Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, were of Irish ancestry. The sixth of ten children, Buckley moved as a boy with his family to Mexico, and then to Sharon, Connecticut, before beginning his formal schooling in Paris, where he attended first grade. By age seven, he received his first formal training in English at a day school in London; his first and second languages were Spanish and French. As a boy, Buckley developed a love for music, sailing, horses, hunting, and skiing. All of these interests would be reflected in his later writings. Just before World War II, at age 12–13, he attended the Catholic preparatory school St. John's Beaumont School in England.