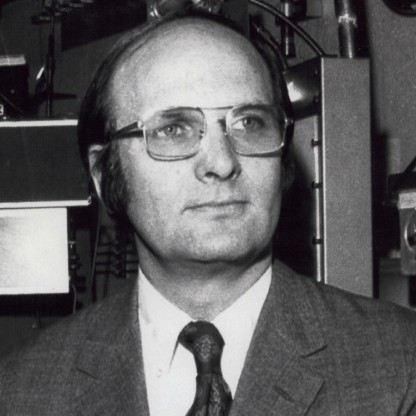

Libby was an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society. In addition to the Nobel Prize, he received numerous honors and awards, including Columbia University's Chandler Medal in 1954, the Remsen Memorial Lecture Award in 1955, the Bicentennial Lecture Award from the City College of New York and the Nuclear Applications in Chemistry Award in 1956, the Franklin Institute's Elliott Cresson Medal in 1957, the American Chemical Society's Willard Gibbs Award in 1958, the Joseph Priestley Award from Dickinson College and the Albert Einstein Medal in 1959, the Geological Society of America's Arthur L. Day Medal in 1961, the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Chemists in 1970, and the Lehman Award from the New York Academy of Sciences in 1971. He was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1950. Analy High School library has a mural of Libby, and a Sebastopol city park and a nearby highway are named in his honor. His 1947 paper on radiocarbon dating was honored by a Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award from the Division of History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society presented to the University of Chicago in 2016.