| Who is it? | Archaeologist and Philologist |

| Birth Day | April 14, 1892 |

| Birth Place | Sydney, Australian |

| Age | 127 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 19 October 1957(1957-10-19) (aged 65)\nBlackheath, New South Wales, Australia |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Alma mater | University of Sydney Oxford University |

| Occupation | Archaeologist Philologist |

| Known for | Excavating Skara Brae Marxist archaeological theory |

V. Gordon Childe, a renowned archaeologist and philologist from Australia, is projected to have a net worth ranging between $100K and $1M by 2025. Childe gained widespread recognition for his ground-breaking contributions to the field of archaeology. With an expertise in prehistoric European cultures, Childe's research and publications have significantly influenced the understanding of human history. Known for his innovative theories and rigorous methodology, Childe's work has left an indelible mark on the discipline. During his career, he held various academic positions and conducted extensive archaeological excavations across Europe. Today, Childe is celebrated as one of the most influential figures in the study of human civilization.

Childe was born on 14 April 1892 in Sydney, New South Wales. He was the only surviving child of the Reverend Stephen Henry (1844–1923) and Harriet Eliza (1853–1910), a middle-class couple of English descent. Stephen Childe was a second-generation Anglican priest, ordained into the Church of England in 1867 after gaining a BA from the University of Cambridge. Becoming a Teacher, in 1871 he married Mary Ellen Latchford, with whom he had five children. They moved to Australia in 1878. It was here that Mary died, and in 1886 Stephen married Harriet, an Englishwoman from a wealthy background who had moved to Australia as a child. Gordon Childe was raised alongside five half-siblings at his father's palatial country house, the Chalet Fontenelle, in the township of Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. Reverend Stephen Childe worked as the minister for St. Thomas' Parish, but proved unpopular, arguing with his congregation and taking unscheduled holidays.

A sickly child, Gordon Childe was educated at home for a number of years, before receiving a private school education in North Sydney. In 1907, he began attending Sydney Church of England Grammar School, gaining his Junior Matriculation in 1909 and Senior Matriculation in 1910. At school he studied ancient history, French, Greek, Latin, geometry, algebra and trigonometry, achieving good marks in all subjects, but he was bullied because of his strange appearance and unathletic physique. In July 1910 his mother died; his father soon took Monica Gardiner as his third wife. Childe's relationship with his father was strained, particularly following his mother's death, and they disagreed on the subjects of religion and politics, with the Reverend being a devout Christian and conservative while his son was an atheist and socialist.

Childe studied for a degree in Classics at the University of Sydney in 1911; although focusing on the study of written sources, he first came across classical archaeology through the works of archaeologists Heinrich Schliemann and Arthur Evans. At university, he became an active member of the Debating Society, at one point arguing in favour of the proposition that "socialism is desirable". Increasingly interested in socialism, he read the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, as well as those of Philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whose ideas on dialectics heavily influenced Marxist theory. Also while there, he became a great friend of fellow undergraduate Herbert Vere Evatt, with whom he remained in contact throughout his life. Ending his studies in 1913, Childe graduated the following year with various honours and prizes, including Professor Francis Anderson's prize for Philosophy.

Wishing to continue his education, he gained a £200 Cooper Graduate Scholarship in Classics, allowing him to afford the tuition fees at Queen's College, a part of the University of Oxford, England. He set sail for Britain aboard the SS Orsova in August 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I. At Queen's, Childe was entered for a diploma in classical archaeology followed by a Literae Humaniores degree, although he never completed the former. Whilst there, he studied under John Beazley and Arthur Evans, the latter acting as Childe's supervisor. In 1915, he published his first academic paper, "On the Date and Origin of Minyan Ware", which appeared in the Journal of Hellenic Studies, and the following year produced his B.Litt. thesis, "The Influence of Indo-Europeans in Prehistoric Greece", displaying his interest in combining philological and archaeological evidence.

At Oxford he became actively involved with the socialist movement, antagonising the conservative university authorities. Becoming a noted member of the left-wing reformist Oxford University Fabian Society, then at the height of its power and membership, he was there in 1915 when it changed its name to the Oxford University Socialist Society, following a split from the Fabian Society. His best friend and flatmate was Rajani Palme Dutt, a British citizen born to an Indian father and Swedish mother, who was a fervent socialist and Marxist. The two often got drunk and tested each other's knowledge about classical history late at night. With Britain in the midst of World War I, many socialists refused to fight for the British Army despite the government imposed conscription. They believed that the war was being waged in the interests of the ruling classes of the European imperialist nations at the expense of the working classes, and that class war was the only conflict that they should be concerned with. Dutt was imprisoned for refusing to fight, and Childe campaigned for his release and the release of other socialists and pacifist conscientious objectors. Childe was never required to enlist in the army, most likely because of his poor health and eyesight. The authorities were concerned by his anti-war sentiments; the intelligence agency MI5 opening a file on him, his mail was intercepted, and he was kept under observation.

Unable to find an academic job in Australia, Childe remained in Britain, renting a room in Bloomsbury, Central London, and spending much time studying at the British Museum and the Royal Anthropological Institute library. An active member of the London socialist movement, he associated with leftists at the 1917 Club in Gerrard Street, Soho, and befriended members of the Marxist Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), contributing to their publication, Labour Monthly; however he had not yet openly embraced Marxism. Having earned a reputation as an excellent prehistorian, he was invited to other parts of Europe in order to study prehistoric artefacts. In 1922 he travelled to Vienna, Austria to examine unpublished material about the painted Neolithic pottery from Schipenitz, Bukovina held in the Prehistoric Department of the Natural History Museum; he published his findings in the 1923 Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Childe used this excursion to visit a number of museums in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, bringing them to the attention of British archaeologists in a 1922 article published in Man. Returning to London, in 1922 Childe became a private secretary for three Members of Parliament, including John Hope Simpson and Frank Gray, both members of the centre-left Liberal Party. Supplementing this income, Childe worked as a translator for the publishers Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co and occasionally lectured in prehistory at the London School of Economics.

With his good academic reputation, several staff members provided him with work as a tutor in ancient history in the Department of Tutorial Classes, but he was prevented from doing so by the chancellor of the University, Sir william Cullen, who feared that Childe would propagate socialism to students. This infringement of Childe's civil rights was condemned in the leftist community, and the issue was brought up in the Parliament of Australia by centre-left politicians william McKell and T.J. Smith. Moving to Maryborough, Queensland, in October 1918, Childe took up employment teaching Latin at the Maryborough Grammar School. Here, too, his political affiliations became known, and he was subject to an opposition campaign from local conservative groups and the Maryborough Chronicle, resulting in abuse from disobedient pupils. He soon resigned.

Realising that an academic career would be barred from him by the right wing university authorities, Childe turned to getting a job within the leftist movement. In August 1919, he became private secretary and speech Writer to Politician John Storey, a prominent member of the centre-left Australian Labor Party then in opposition to New South Wales' Nationalist government. Representing the Sydney suburb of Balmain on the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Storey became state premier in 1920 when Labor achieved an electoral victory there. Working within the Labor Party allowed Childe to gain an "unrivalled grasp of its structure and history", enabling him to write a book on the subject, How Labour Governs (1923). The greater his involvement, the more Childe became critical of Labor, believing that they betrayed their socialist ideals once they gained political power and moved to a centrist, pro-capitalist stance. He joined the Industrial Workers of the World, which in Australia served mostly as a centre of radical labourers within existing unions, and at the time was banned by the government as a political threat. In 1921 Childe was sent to London by Storey, in order to keep the British press updated about developments in New South Wales, but in December Storey died, and a few days later the New South Wales elections restored a Nationalist government under the premiership of George Fuller. Fuller thought Childe's job unnecessary, and in early 1922 terminated his employment.

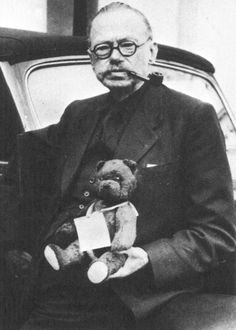

Childe's other hobbies included walking in the British hillsides, attending classical music concerts, and playing the card game contract bridge. Fond of poetry, his favourite poet was John Keats, although his favourite poems were william Wordsworth's "Ode to Duty" and Robert Browning's "A Grammarian's Funeral". He was not particularly interested in reading novels but his favourite was D. H. Lawrence's Kangaroo (1923), a book echoing many of Childe's own feelings about Australia. He was a fan of good quality food and drink, and frequented a number of restaurants. Known for his battered, tatty attire, Childe always wore his wide-brimmed black hat, which he had purchased from a hatter in Jermyn Street, central London, as well as a tie, which was usually red, a colour chosen to symbolise his socialist beliefs. He regularly wore a black Mackintosh raincoat, often carrying it over his arm or draped over his shoulders like a cape. In summer he frequently wore shorts with socks, sock suspenders, and large boots.

In 1925, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co published Childe's second book, The Dawn of European Civilisation, in which he synthesised the varied data about European prehistory that he had been exploring for many years. An important work, it was released when the few archaeologists across Europe were amateur and focused purely on studying their locality; The Dawn was a rare Example that looked at the larger picture across the continent. Its importance was also due to the fact that it introduced the concept of the archaeological culture into Britain from continental scholarship, thereby aiding in the development of culture-historical archaeology. Childe later stated that the book "aimed at distilling from archaeological remains a preliterate substitute for the conventional politico-military history with cultures, instead of statesmen, as actors, and migrations in place of battles." In 1926 he published a successor, The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins, exploring the theory that civilisation diffused northward and westward into Europe from the Near East via an Indo-European linguistic group known as the Aryans; with the ensuing racial use of the term "Aryan" by the German Nazi Party, Childe avoided mention of the book. In these works, Childe accepted a moderate diffusionism, believing that although most cultural traits spread from one society to another, it was possible for the same traits to develop independently in different places, a theory at odds with the hyper-diffusionism of Grafton Elliot Smith.

In 1927, Childe was offered the newly created post of Abercromby Professor of Archaeology at Scotland's University of Edinburgh (at what is now the School of History, Classics and Archaeology), established by deed poll in the bequest of prehistorian Lord John Abercromby. Although sad at leaving London, Childe took the prestigious position, moving to Edinburgh in September 1927. Aged 35, Childe became the "only academic prehistorian in a teaching post in Scotland", and was disliked by many Scottish archaeologists, who viewed him as an outsider with no specialism in Scottish prehistory; this hostility intensified, and he wrote to a friend, remarking that "I live here in an atmosphere of hatred and envy." He nevertheless made friends in Edinburgh, including Sir W. Lindsay Scott, Alexander Curle, J.G. Callender, Walter Grant and Charles Galton Darwin, becoming godfather to the latter's youngest son. Initially lodging at Liberton, he moved into the semi-residential Hotel de Vere in Eglington Crescent.

Childe continued writing and publishing books on archaeology, beginning with a series of works following on from The Dawn of European Civilisation and The Aryans by compiling and synthesising data from across Europe. First was The Most Ancient Near East (1928), which assembled information from across Mesopotamia and India, setting a background from which the spread of farming and other technologies into Europe could be understood. This was followed by The Danube in Prehistory (1929) which examined the archaeology along the Danube river, recognising it as the natural boundary dividing the Near East from Europe; Childe believed that it was via the Danube that new technologies travelled westward in prehistory. The book introduced the concept of an archaeological culture to Britain from Germany, revolutionising the theoretical approach of British archaeology.

Marxist archaeology had developed in the Soviet Union in 1929, when the young archaeologist Vladislav I. Ravdonikas published a report titled "For a Soviet history of material culture". Criticising the archaeological discipline as inherently bourgeois and therefore anti-socialist, Ravdonikas's report called for the adoption of a pro-socialist, explicitly Marxist approach to archaeology that was a part of the academic reforms instituted under the administration of Joseph Stalin. Although influenced by Soviet archaeology, Childe maintained a sceptical approach to much of it, disapproving of how the Soviet government encouraged the country's archaeologists to assume their conclusions in advance of analysing the data. He was also critical of what he saw as the sloppy approach to typology adopted within Soviet archaeology.

On his death, Childe was praised by his colleague Stuart Piggott as "the greatest prehistorian in Britain and probably the world". The archaeologist Randall H. McGuire later described him as "probably the best known and most cited archaeologist of the twentieth century", an idea echoed by Bruce Trigger, while Barbara McNairn labelled him "one of the most outstanding and influential figures in the discipline". The archaeologist Andrew Sherratt described Childe as occupying "a crucial position in the history" of archaeology. Sherratt also noted that "Childe's output, by any standard, was massive". Over the course of his career, Childe published over twenty books and around 240 scholarly articles. The archaeologist Brian Fagan described his books as "simple, well-written narratives" which became "archaeological canon between the 1930s and early 1960s". By 1956, he was cited as the most translated Australian author in history, having seen his books published in such languages as Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Hindi, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Russian, Spanish, Sweden and Turkish. The archaeologists David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce considered Childe to be "probably the most written about" archaeologist in history, commenting that his books were still "required reading" for those in the discipline in 2005.

In 1933, Childe travelled to Asia, visiting Iraq – a place he thought "great fun" – and India, which he felt was "detestable" due to the hot weather and extreme poverty. Touring archaeological sites in the two countries, he opined that much of what he had written in The Most Ancient Near East was outdated, going on to produce New Light on the Most Ancient Near East (1935), applying his Marxist-influenced ideas about the economy to his conclusions.

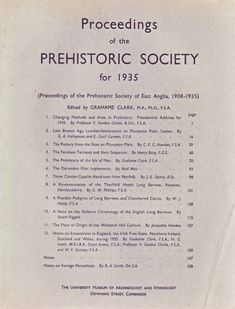

Childe introduced his ideas about "revolutions" in a presidential address given to the Prehistoric Society in 1935, as part of his functional-economic interpretation of the three-age system. Here, he argued for a "Neolithic Revolution" which initiated the Neolithic era, and also believed that there were others that marked the start of the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. The following year, in Man Makes Himself, he combined these Bronze and Iron Age Revolutions into a singular "Urban Revolution," which corresponded largely to the Anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan's concept of "civilization."

Located in St John's Lodge in the Inner Circle of Regent's Park, the IOA was founded in 1937, largely by archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, but until 1946 relied primarily upon volunteer lecturers. Childe's relationship with the conservative Wheeler was strained, the latter being intolerant of the shortcomings of others, something Childe made an effort never to be. He was popular among students, who saw him as a kindly eccentric; they commissioned a bust of Childe from Marjorie Maitland Howard. His lecturing was nevertheless considered poor, as he often mumbled and walked into an adjacent room to find something while continuing to talk. He consistently referred to the socialist states of eastern Europe by their full official titles, and called towns by their Slavonic rather than Germanic names, further confusing his students. He was deemed better at giving tutorials and seminars, where he devoted more time to interacting with his students. As Director, Childe was not obliged to excavate, though he did undertake projects at the Orkney Neolithic burial tombs of Quoyness (1951) and Maes Howe (1954–55).

Despite his global influence, Childe's oeuvre was poorly understood in the United States, where his work on European prehistory had never become well known. As a result, in the U.S. he erroneously gained the reputation of being a Near Eastern specialist, where he was regarded by anthropologists as one of the founders of neo-evolutionism, alongside Julian Steward and Leslie White, despite the fact that his approach was "more subtle and nuanced" than theirs. Steward repeatedly misrepresented Childe as a unilinear evolutionist in his writings, perhaps as part of an attempt to distinguish his own "multilinear" evolutionary approach from the ideas of Marx and Engels. In contrast to this American neglect and misrepresentation, Trigger believed that it was an American archaeologist, Robert McCormick Adams, Jr., who did the more to develop Childe's "most innovative ideas" after the latter's death than anyone else. He also had a small following of American archaeologists and anthropologists in the 1940s who wanted to bring back materialist and Marxist ideas into their research after years in which Boasian particularism had been hegemonic within the discipline.

In 1946, Childe left Edinburgh to take up the position as Director and professor of European prehistory at the Institute of Archaeology (IOA) in London. Anxious to return to the capital, he had kept silent over his disapproval of government policies so that he would not be prevented from getting the job. He took up residence at Lawn Road Flats near to Hampstead.

Childe was an atheist and critic of religion, viewing it as a false consciousness based in superstition that served the interests of dominant elites. In History (1947) he commented that "Magic is a way of making people believe they are going to get what they want, whereas religion is a system for persuading them that they ought to want what they get." He nevertheless regarded Christianity as being evolutionary superior over what he regarded as primitive religion, commenting that "Christianity as a religion of love surpasses all others in stimulating positive virtue". In a letter written during the 1930s, he stated that "only in days of exceptional bad temper do I Desire to hurt peoples' religious convictions".

In 1949 he and O.G.S. Crawford resigned as fellows of the Society of Antiquaries in protest at the election of James Mann to the presidency following the retirement of Cyril Fox. They believed that Mann, keeper of the tower's armouries at the Tower of London, was a poor choice and that Wheeler, an actual prehistorian, should have won the election. In 1952 a group of British Marxist historians began publishing the periodical Past & Present, with Childe joining the editorial board. He also became a board member for The Modern Quarterly (later The Marxist Quarterly) during the early 1950s, working alongside old friend, the Communist leader, Rajani Palme Dutt, chairman of the board. He authored occasional articles for Palme Dutt's socialist journal, the Labour Monthly, but disagreed with him over the Hungarian Revolution of 1956; Palme Dutt defended the Soviet Union's decision to quash the revolution using military force, but like many Western socialists, Childe strongly disagreed. The event made Childe abandon faith in the Soviet leadership, but not in socialism and Marxism. Childe retained a love of the Soviet Union, having visiting on multiple occasions and having been involved with CPBG satellite body the Society for Cultural Relations with the USSR, and serving as President of their National History and Archaeology Section from the early 1950s until his death.

In the summer of 1956, Childe retired as IOA Director a year prematurely. European archaeology had rapidly expanded during the 1950s, leading to increasing specialisation and making the synthesising that Childe was known for increasingly difficult. That year, the institute was moving to Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, and Childe wanted to give his successor, W.F. Grimes, a fresh start in the new surroundings. To commemorate his achievements, the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society published a Festschrift edition on the last day of his directorship containing contributions from friends and colleagues from all over the world, something that touched Childe deeply. Upon his retirement, he told many friends that he planned to return to Australia, visit his relatives, and then commit suicide; he was terrified of becoming old, senile, and a burden on society, and suspected that he had cancer. Subsequent commentators have suggested that a core reason for his suicidal desires was his loss of faith in Marxism following the Hungarian Revolution and Premier Nikita Khrushchev's denouncement of Joseph Stalin, although Bruce Trigger noted that while Childe was critical of the Soviet Union's foreign policy, he never saw the state and Marxism as "synonymous", thereby dismissing this explanation.

Writing personal letters to many friends, he sent one to Grimes, requesting that it not be opened until 1968. In it, he described how he feared old age, and stated his intention to take his own life, remarking that "Life ends best when one is happy and strong." On 19 October 1957, Childe went to the area of Govett's Leap in Blackheath in the Blue Mountains where he had grown up. Leaving his hat, spectacles, compass, pipe and Mackintosh atop the cliffs, he fell 1000 feet (300 m) to his death. A coroner ruled his death as accidental, although in the 1980s the Grimes letter saw publication, allowing for recognition of his suicide. His remains were cremated at the Northern Suburbs Crematorium, and his name added to a small family plaque in the Crematorium Gardens. Following his death, an "unprecedented" level of tributes and memorials were issued by the archaeological community, all testifying to his status as Europe's "greatest prehistorian and a wonderful human being."

Following his death, various articles were published that examined Childe's work from a historical perspective. In 1980, Bruce Trigger published Gordon Childe: Revolutions in Archaeology, which studied the influences that extended over Childe's archaeological thought. That year, Barbara McNairn published The Method and Theory of V. Gordon Childe, examining his methodological and theoretical approaches to the discipline. The following year, Sally Green's Prehistorian: A Biography of V. Gordon Childe, was published, in which she described him as "the most eminent and influential scholar of European prehistory in the twentieth century". Peter Gathercole thought the work of Trigger, McNairn and Green to have been "extremely important", while Ruth Tringham considered them part of a "let's-get-to-know-Childe-better" movement, expressing her opinion that they were all worth reading.

In July 1986, a colloquium devoted to Childe's work was held in Mexico City, marking the 50th anniversary of Man Makes Himself's publication. In September 1990, the University of Queensland's Australian Studies Centre organised a centenary conference for Childe in Brisbane, with presentations examining both his scholarly and socialist work. In May 1992, a conference marking his centenary was held at the UCL Institute of Archaeology in London, co-sponsored by the Institute and the Prehistoric Society, both organisations that he had formerly headed. The proceedings of the conference were subsequently published in a 1994 volume edited by Institute Director David R. Harris, The Archaeology of V. Gordon Childe: Contemporary Perspectives. Harris stated that the book was designed to "demonstrate the dynamic qualities of Childe's thought, the breadth and depth of his scholarship, and the continuing relevance of his work to contemporary issues in archaeology." In 1995, another anthology based on a conference was published. Titled Childe and Australia: Archaeology, Politics and Ideas, it was edited by Peter Gathercole, T.H. Irving, and Gregory Melleuish. Further papers would appear on the subject of Childe in ensuing years, looking at such subjects as his personal correspondences, and final resting place.

Childe is primarily respected for developing a synthesis of European and Near Eastern prehistory at a time when most archaeologists were focused on regional sites and sequences, gaining the moniker of "the Great Synthesizer". Since his death, this framework has been heavily revised following the discovery of radiocarbon dating, while his interpretations have been "largely rejected". Many of the conclusions about Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe that Childe produced have since been found to be incorrect. Various archaeologists have debated and disagreed over the importance of various different parts of Childe's work. Childe himself believed that his primary contribution to archaeology was in his interpretative frameworks, an analysis supported by Alison Ravetz and Peter Gathercole. According to Sherratt: "What is of lasting value in his interpretations is the more detailed level of writing, concerned with the recognition of patterns in the material he described. It is these patterns which survive as classic problems of European prehistory, even when his explanations of them are recognised as inappropriate." Childe's theoretical work had been largely ignored in his lifetime, and remained forgotten in the decades after his death, although would see a resurgence in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It remained best known in Latin America, where Marxism remained a core theoretical current in the archaeological community throughout the latter 20th century.

Childe is referenced in the American blockbuster film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Directed by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, the motion picture was the fourth film in the Indiana Jones series that dealt with the eponymous fictional archaeologist and university professor. In the film, Jones is heard advising one of his students that to understand the concept of diffusion he must read the works of Childe.

Childe believed that the study of the past could offer guidance for how humans should act in the present and Future. He was known for his radical left-wing views, being a socialist from his undergraduate days. He sat on the committees of various left-wing groups although avoided involvement in Marxist intellectual arguments within the Communist Party and—with the exception of How Labour Governs—did not commit his non-archaeological opinions to print. Many of his political views are therefore only evident through comments made in his private correspondences. The archaeologist Colin Renfrew noted that Childe was liberal minded on social issues, but thought that although Childe deplored racism, he did not entirely escape the pervasive 19th century view on distinct differences between different races. In a private letter that Childe wrote to the archaeologist Christopher Hawkes, he stated that he disliked Jews.