| Who is it? | Civil Engineer |

| Birth Day | November 07, 1805 |

| Birth Place | Buerton, British |

| Age | 214 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 8 December 1870 (1870-12-09) (aged 65)\nSt Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex, England |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Occupation | Civil engineering contractor |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Harrison |

| Children | Thomas, Harry, Albert |

| Parent(s) | John and Elizabeth Brassey |

Thomas Brassey, a renowned Civil Engineer in British history, is expected to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in 2025. His exceptional contribution to the field of engineering has attributed to his prestigious reputation. Throughout his career, Brassey has been involved in numerous significant infrastructure projects, including railway constructions and bridge designs. His expertise and mastery have allowed him to accumulate substantial wealth, reflecting his invaluable contributions to the industry.

Thomas Brassey was educated at home until the age of 12, when he was sent to The King's School in Chester. Aged 16, he became an articled apprentice to a land surveyor and agent, william Lawton. Lawton was the agent of Francis Richard Price of Overton, Flintshire. During the time Brassey was an apprentice he helped to survey the new Shrewsbury to Holyhead road (this is now the A5), assisting the surveyor of the road. While he was engaged in this work he met the Engineer for the road, Thomas Telford. When his apprenticeship ended at the age of 21, Brassey was taken into partnership by Lawton, forming the firm of "Lawton and Brassey". Brassey moved to Birkenhead where their Business was established. Birkenhead at that time was a very small place; in 1818 it consisted of only four houses. The Business flourished and grew, extending into areas beyond land surveying. At the Birkenhead site a brickworks and lime kilns were built. The Business either owned or managed sand and stone quarries in Wirral. Amongst other ventures, the firm supplied the bricks for building the custom house for the port which was developing in the town. Many of the bricks needed for the growing city of Liverpool were supplied by the brickworks and Brassey devised new methods of transporting his materials, including a system similar to the modern method of palletting, and using a gravity train to take materials from the quarry to the port. When Lawton died, Brassey became sole manager of the company and sole agent and representative for Francis Price. It was during these years that he gained the basic experience for his Future career.

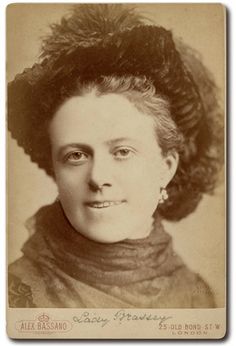

In 1831 he married Maria Harrison, the second daughter of Joseph Harrison, a forwarding and shipping agent with whom he had come into contact during his early days in Birkenhead. Maria gave Thomas considerable support and encouragement throughout his career. She encouraged him to bid for the contract for Dutton Viaduct and, when that was unsuccessful, to apply for the next available contract. Thomas' work led to frequent moves of home in their early years; from Birkenhead to Stafford, Kingston upon Thames, Winchester and then Fareham. On each occasion Maria supervised the packing of their possessions and the removal. The Harrison children had been taught to speak French, while Thomas himself was unable to do so. Therefore, when the opportunity arose to apply for the French contracts, Maria was willing to act as interpreter and encouraged Thomas to bid for them. This resulted in moves to Vernon in Normandy, then to Rouen, on to Paris and back again to Rouen. Thomas refused to learn French and Maria acted as interpreter for all his French undertakings. Maria organised the education of their three sons. In time the family established a more-or-less permanent base in Lowndes Square, Belgravia, London. They had three sons, who all gained distinction in their own right:

Brassey's first experiences of civil engineering were the construction of 4 miles (6 km) of the New Chester Road at Bromborough, and the building of a bridge at Saughall Massie, on the Wirral. During that time he met George Stephenson, who needed stone to build the Sankey Viaduct on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Stephenson and Brassey visited a quarry in Storeton, a village near Birkenhead, following which Stephenson advised Brassey to become involved in building railways. Brassey's first venture into railways was to submit a tender for building the Dutton Viaduct on the Grand Junction Railway, but he lost the contract to william Mackenzie, who had submitted a lower bid. In 1835 Brassey submitted a tender for building the Penkridge Viaduct, further south on the same railway, between Stafford and Wolverhampton, together with 10 miles (16 km) of track. The tender was accepted, the work was successfully completed, and the viaduct opened in 1837. Initially the Engineer for the line was George Stephenson, but he was replaced by Joseph Locke, Stephenson's pupil and assistant. During this time Brassey moved to Stafford. Penkridge Viaduct still stands and carries trains on the West Coast Main Line.

Following the success of the early railways in Britain, the French were encouraged to develop a railway network, in the first place to link with the railway system in Britain. To this end the Paris and Rouen Railway Company was established, and Locke was appointed as its Engineer. He considered that the tenders submitted by French contractors were too expensive, and suggested that British contractors should be invited to tender. In the event only two British contractors took the offer seriously, Brassey and william Mackenzie. Instead of trying to outbid each other they tendered jointly, and their tender was accepted in 1841. This set a pattern for Brassey, who from then on worked in partnership with other contractors in most of his ventures. Between 1841 and 1844 Brassey and Mackenzie won contracts to build four French railways, with a total mileage of 437 miles (703 km), the longest of which was the 294-mile (473 km) Orléans and Bordeaux Railway. Following the French revolution of 1848 there was a financial crisis in the country and investment in the railways almost ceased. This meant that Brassey had to seek foreign contracts elsewhere.

During the time Brassey was building the early French railways, Britain was experiencing what was known as the "railway mania", when there was massive investment in the railways. Large numbers of lines were being built, but not all of them were built to Brassey's high standards. Brassey was involved in this expansion but was careful to choose his contracts and Investors so that he could maintain his standards. During the one year of 1845 he agreed no less than nine contracts in England, Scotland and Wales, with a mileage totalling over 340 miles (547 km). In 1844 Brassey and Locke began building the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway of 70 miles (113 km), which was considered to be one of their greatest lines. It passed through the Lune Valley and then over Shap Fell. Its summit was 916 feet (279 m) high and the line had steep gradients, the maximum being 1 in 75. To the south the line linked by way of the Preston–Lancaster line to the Grand Junction Railway. Two important contracts undertaken in 1845 were the Trent Valley Railway of 50 miles (80 km) and the Chester and Holyhead line of 84 miles (135 km). The former line joined the London and Birmingham Railway at Rugby to the Grand Junction Railway south of Stafford providing a line from London to Scotland which bypassed Birmingham. The latter line provided a link between London and the ferries sailing from Holyhead to Ireland and included Robert Stephenson's tubular Britannia Bridge over the Menai Strait. Also in 1845 Brassey received contracts for the Caledonian Railway which linked the railway at Carlisle with Glasgow and Edinburgh, covering a total distance of 125 miles (201 km) and passing over Beattock Summit. His Engineer on this project was George Heald. That same year he also began contracts for other railways in Scotland, and in 1846 he started building parts of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway between Hull and Liverpool, across the Pennines.

In January 1846, during the building of the 58-mile (93 km) long Rouen and Le Havre line, one of the few major structural disasters of Brassey's career occurred, the collapse of the Barentin Viaduct. The viaduct was built of brick at a cost of about £50,000 and was 100 feet (30 m) high. The reason for the collapse was never established, but a possible cause was the nature of the lime used to make the mortar. The contract stipulated that this had to be obtained locally, and the collapse occurred after a few days of heavy rain. Brassey rebuilt the viaduct at his own expense, this time using lime of his own choice. The rebuilt viaduct still stands and is in use today.

A contract for the Great Northern Railway was agreed in 1847, with william Cubitt as engineer-in-chief, although much of the work was done by William's son Joseph, who was the resident Engineer. Brassey was the sole contractor for the line of 75.5 miles (122 km). A particular Problem was met in the marshy country of The Fens in providing a firm foundation for the railway and associated structures. Brassey was assisted in solving the Problem by one of his agents, Stephen Ballard. Rafts or platforms were made of layers of faggot-wood and peat sods. As these sank, they dispersed the water and so a firm foundation was made. This line is still in use and forms part of the East Coast Main Line. Also in 1847 Brassey began to build the North Staffordshire Railway. By this time the "railway mania" was coming to an end and contracts in Britain were becoming increasingly more difficult to find. By the end of the "railway mania", Brassey had built one-third of all the railways in Britain.

Following the end of the "railway mania" and the drying up of contracts in France, Brassey could have retired as a rich man. Instead he decided to expand his interests, initially in other European countries. His first venture in Spain was the Barcelona and Mataró Railway of 18 miles (29 km) in 1848. In 1850 he undertook his first contract in the Italian States, a short railway of 10 miles (16 km), the Prato and Pistoia Railway. This was to lead to bigger contracts in Italy, the next being the Turin–Novara line of 60 miles (97 km) in 1853, followed by the Central Italian Railway of 52 miles (84 km). In Norway, with Sir Morton Peto and Edward Betts, Brassey built the Oslo to Bergen Railway of 56 miles (90 km) which passes through inhospitable terrain and rises to nearly 6,000 feet (1,829 m). In 1852 he resumed work in France with the Mantes and Caen Railway of 133 miles (214 km) and, in 1854, the Caen and Cherbourg Railway of 94 miles (151 km). The Dutch were relatively slow to start building railways but in 1852 with Locke as Engineer, Brassey built the Dutch Rhenish Railway of 43 miles (69 km). Meanwhile, he continued to build lines in England, including the Shrewsbury and Hereford Railway of 51 miles (82 km), the Hereford, Ross and Gloucester Railway of 50 miles (80 km), the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway of 50 miles (80 km) and the North Devon Railway from Minehead to Barnstaple of 47 miles (76 km).

Brassey's works were not limited to railways and associated structures. In addition to his factories in Birkenhead, he built an engineering works in France to supply materials for his contracts there. He built a number of drainage systems, and a waterworks at Calcutta. Brassey built docks at Greenock, Birkenhead, Barrow-in-Furness and London. His London docks were the Victoria Docks which had a water area of over 100 acres (40 ha). The contract for this was agreed in 1852 in partnership with Peto and Betts and the docks were opened in 1857. Also included in the contract were warehouses and wine vaults totalling an area of about 25 acres (10 ha). The dockside machinery was worked by hydraulic power supplied by william Armstrong. The dock had links to Brassey's London, Tilbury and Southend Railway and thereby to the entire British rail system.

Brassey gave financial help to Brunel to build his ship The Leviathan, which was later called The Great Eastern and which in 1854 was six times larger than any other vessel in the world. Brassey was a major shareholder in the ship and after Brunel's death, he, together with Gooch and Barber, bought the ship for the purpose of laying the first Transatlantic telegraph cable across the North Atlantic in 1864.

In 1861 Brassey built part of the London sewerage system for Joseph Bazalgette. This was a stretch of the Metropolitan Mid Level Sewer of 12 miles (19 km) which started at Kensal Green, passed under Bayswater Road, Oxford Street and Clerkenwell to the River Lea. It was one of the earliest ventures to use steam cranes. The undertaking was considered to have been one of Brassey's most difficult. The sewer is still in operation today. He also worked with Bazalgette to build the Victoria Embankment on the north bank of the River Thames from Westminster Bridge to Blackfriars Bridge.

As well as railway engineering, Brassey was active in the development of steamships, mines, locomotive factories, marine telegraphy, and water supply and sewage systems. He built part of the London sewerage system, still in operation today, and was a major shareholder in Brunel's The Great Eastern, the only ship large enough at the time to lay the first transatlantic telegraph cable across the North Atlantic, in 1864.

In 1866 there was a great economic slump, caused by the collapse of the bank of Overend, Gurney and Company, and many of Brassey's colleagues and competitors became insolvent. However, despite setbacks, Brassey survived the crisis and drove ahead with the projects he already had in hand. These included the Lemberg and Czernowicz Railway in Austria which continued to be constructed despite the Austro-Prussian War which was taking place in the locality.

When Brassey's Business friend, Edward Betts, became insolvent in 1867, Brassey bought Betts' estate at Preston Hall, Aylesford in Kent on behalf of his second son, Henry.

On 8 December 1870 Thomas Brassey died from a brain haemorrhage in Victoria Hotel, St Leonards and was buried in the churchyard of St Laurence's Church, Catsfield, Sussex where a memorial stone has been erected. His estate was valued at £5,200,000 which consisted of "under £3,200,000 in UK" and "over £2,000,000" in a trust fund. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography describes him as "one of the wealthiest of the self-made Victorians".

Walker, in his 1969 biography, tried to make an accurate assessment of Brassey using Helps and other sources. He found it difficult to discover anyone who had a bad word to say about him, either during his life or since. Brassey expected a high standard of work from his employees; Cooke states that his "standards of quality were fastidious in the extreme". There can be no doubt about some of his qualities. He was exceptionally hardworking, and had an excellent memory and ability to perform mental arithmetic. He was a good judge of men, which enabled him to select the best people to be his agents. He was scrupulously fair with his subcontractors and kind to his navvies, supporting them financially at their times of need. He would at times undertake contracts of little benefit to himself to provide work for his navvies. The only faults which his eldest son could identify were a tendency to praise traits and actions of other people he would condemn in his own family, and an inability to refuse a request. No criticism of him could be found from the Engineers with whom he worked, his Business associates, his agents or his navvies. He paid his men fairly and generously.

In November 2005, Penkridge celebrated the bicentenary of Brassey's birth and a special commemorative train was run from Chester to Holyhead. In January 2007, children from Overchurch Junior School in Upton, Wirral celebrated the life of Brassey. In April 2007 a plaque was placed on Brassey's first bridge at Saughall Massie. In the village of Bulkeley, near Malpas, Cheshire, is a tree called the 'Brassey Oak' on land once owned by the Brassey family. This was planted to celebrate Thomas' 40th birthday in 1845. It was surrounded by four inscribed sandstone pillars tied together by iron rails but due to the growth of the tree these burst and the stones fell. They were recovered and in 2007 were replaced in a more accessible place with an information board.