| Who is it? | 10th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire |

| Birth Day | November 06, 1494 |

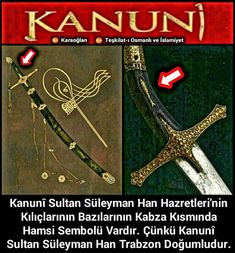

| Birth Place | Trabzon, Ottoman Empire, Turkish |

| Age | 525 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 6 September 1566(1566-09-06) (aged 71)\nSzigetvár, Kingdom of Hungary |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Reign | 30 September 1520 – 6 September 1566 |

| Sword girding | 30 September 1520 |

| Predecessor | Selim I |

| Successor | Selim II |

| Burial | Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul |

| Consorts | Hurrem Sultan (legal wife) Mahidevran Sultan |

| Issue | Şehzade Mahmud Şehzade Mustafa Şehzade Mehmed Şehzade Murad Mihrimah Sultan Şehzade Abdullah Selim II Raziye Sultan Şehzade Bayezid Şehzade Cihangir Sehzade Ibrahim Şehzade Orhan |

| Full name | Full name Süleyman bin Selim Süleyman bin Selim |

| Dynasty | Ottoman |

| Father | Selim I |

| Mother | Hafsa Sultan |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Suleiman The Magnificent, also known as the 10th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire in Turkish, is estimated to have a net worth between $100K and $1M in 2025. Suleiman was renowned for his accomplishments in expanding the empire's territory, cultural influence, and economic prosperity during his reign from 1520 to 1566. Often referred to as the Golden Age of the Ottoman Empire, his rule saw significant advancements in areas such as art, architecture, and literature. Suleiman's wealth was acquired through the Empire's vast resources and taxation systems, as well as his successful military campaigns and flourishing trade routes.

Upon the death of his father, Selim I (r. 1512–1520), Suleiman entered Constantinople and ascended to the throne as the tenth Ottoman Sultan. An early description of Suleiman, a few weeks following his accession, was provided by the Venetian envoy Bartolomeo Contarini: "The Sultan is only twenty-five years [actually 26] old, tall and slender but tough, with a thin and bony face. Facial hair is evident but only barely. The Sultan appears friendly and in good humor. Rumor has it that Suleiman is aptly named, enjoys reading, is knowledgeable and shows good judgment." Some historians claim that in his youth Suleiman had an admiration for Alexander the Great.

Ottoman ships had been sailing in the Indian Ocean since the year 1518. Ottoman Admirals such as Hadim Suleiman Pasha, Seydi Ali Reis and Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis are known to have voyaged to the Mughal imperial ports of Thatta, Surat and Janjira. The Mughal Emperor Akbar himself is known to have exchanged six documents with Suleiman the Magnificent.

Upon succeeding his father, Suleiman began a series of military conquests, eventually suppressing a revolt led by the Ottoman-appointed governor of Damascus in 1521. Suleiman soon made preparations for the conquest of Belgrade from the Kingdom of Hungary—something his great-grandfather Mehmed II had failed to achieve because of John Hunyadi's strong defense in the region. Its capture was vital in removing the Hungarians and Croats who, following the defeats of the Albanians, Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Byzantines and the Serbs, remained the only formidable force who could block further Ottoman gains in Europe. Suleiman encircled Belgrade and began a series of heavy bombardments from an island in the Danube. Belgrade, with a garrison of only 700 men, and receiving no aid from Hungary, fell in August 1521.

The road to Hungary and Austria lay open, but Suleiman turned his attention instead to the Eastern Mediterranean island of Rhodes, the home base of the Knights Hospitaller. In the summer of 1522, taking advantage of the large navy he inherited from his father, Suleiman dispatched an armada of some 400 ships towards Rhodes, while personally leading an army of 100,000 across Asia Minor to a point opposite the island itself. Here Suleiman built a large fortification, Marmaris Castle, that served as a base for the Ottoman Navy. Following the brutal five-month Siege of Rhodes (1522), Rhodes capitulated and Suleiman allowed the Knights of Rhodes to depart.

Under Suleiman's patronage, the Ottoman Empire entered the golden age of its cultural development. Hundreds of imperial artistic societies (called the Turkish language text" xml:lang="ota">اهل حرف Ehl-i Hiref, "Community of the Craftsmen") were administered at the Imperial seat, the Topkapı Palace. After an apprenticeship, artists and craftsmen could advance in rank within their field and were paid commensurate wages in quarterly annual installments. Payroll registers that survive testify to the breadth of Suleiman's patronage of the arts, the earliest of documents dating from 1526 list 40 societies with over 600 members. The Ehl-i Hiref attracted the empire's most talented artisans to the Sultan's court, both from the Islamic world and from the recently conquered territories in Europe, resulting in a blend of Arabic, Turkish and European cultures. Artisans in Service of the court included Painters, book binders, furriers, jewellers and goldsmiths. Whereas previous rulers had been influenced by Persian culture (Suleiman's father, Selim I, wrote poetry in Persian), Suleiman's patronage of the arts saw the Ottoman Empire assert its own artistic legacy.

Some Hungarian nobles proposed that Ferdinand, who was ruler of neighboring Austria and tied to Louis II's family by marriage, be King of Hungary, citing previous agreements that the Habsburgs would take the Hungarian throne if Louis died without heirs. However, other nobles turned to the nobleman Ioan Zápolya, who was being supported by Suleiman. Under Charles V and his brother Ferdinand I, the Habsburgs reoccupied Buda and took possession of Hungary. Reacting in 1529, Suleiman marched through the valley of the Danube and regained control of Buda; in the following autumn his forces laid siege to Vienna. This was to be the Ottoman Empire's most ambitious expedition and the apogee of its drive to the West. With a reinforced garrison of 16,000 men, the Austrians inflicted the first defeat on Suleiman, sowing the seeds of a bitter Ottoman-Habsburg rivalry that lasted until the 20th century. His second attempt to conquer Vienna failed in 1532, as Ottoman forces were delayed by the siege of Güns and failed to reach Vienna. In both cases, the Ottoman army was plagued by bad weather, forcing them to leave behind essential siege equipment, and was hobbled by overstretched supply lines.

Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, when the Knights Hospitallers were re-established as the Knights of Malta in 1530, their actions against Muslim navies quickly drew the ire of the Ottomans, who assembled another massive army in order to dislodge the Knights from Malta. The Ottomans invaded Malta in 1565, undertaking the Great Siege of Malta, which began on 18 May and lasted until 8 September, and is portrayed vividly in the frescoes of Matteo Perez d'Aleccio in the Hall of St. Michael and St. George. At first it seemed that this would be a repeat of the battle on Rhodes, with most of Malta's cities destroyed and half the Knights killed in battle; but a relief force from Spain entered the battle, resulting in the loss of 10,000 Ottoman troops and the victory of the local Maltese citizenry.

As Suleiman stabilized his European frontiers, he now turned his attention to the ever-present threat posed by the Shi'a Safavid dynasty of Persia. Two events in particular were to precipitate a recurrence of tensions. First, Shah Tahmasp had the Baghdad governor loyal to Suleiman killed and replaced with an adherent of the Shah, and second, the governor of Bitlis had defected and sworn allegiance to the Safavids. As a result, in 1533, Suleiman ordered his Grand Vizier Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha to lead an army into eastern Asia Minor where he retook Bitlis and occupied Tabriz without resistance. Having joined Ibrahim in 1534, Suleiman made a push towards Persia, only to find the Shah sacrificing territory instead of facing a pitched battle, resorting to harassment of the Ottoman army as it proceeded along the harsh interior. When in the following year Suleiman made a grand entrance into Baghdad, he greatly enhanced his prestige by restoring the tomb of Abu Hanifa, the founder of the Hanafi school of Islamic law to which the Ottomans adhered.

The formation of Suleiman's legacy began even before his death. Throughout his reign literary works were commissioned praising Suleiman and constructing an image of him as an ideal ruler, most significantly by Celalzade Mustafa, chancellor of the empire from 1534–1557. Later Ottoman Writers applied this idealized image of Suleiman to the Near Eastern literary genre of advice literature (naṣīḥatnāme), urging sultans to conform to his model of rulership and to maintain the empire's institutions in their sixteenth-century form. Such Writers were pushing back against the political and institutional transformation of the empire after the middle of the sixteenth century, and portrayed deviation from the norm as it had existed under Suleiman as evidence of the decline of the empire. Western historians, failing to recognize that these 'decline writers' were working within an established literary genre and often had deeply personal reasons for criticizing the empire, long took their claims at face value and consequently adopted the idea that the empire entered a period of decline after the death of Suleiman. Since the 1980s this view has been thoroughly reexamined, and modern scholars have come to overwhelmingly reject the idea of decline, labeling it an "untrue myth."

In 1535, Charles V won an important victory against the Ottomans at Tunis, which together with the war against Venice the following year, led Suleiman to accept proposals from Francis I of France to form an alliance against Charles. In 1538, the Spanish fleet was defeated by Barbarossa at the Battle of Preveza, securing the eastern Mediterranean for the Turks for 33 years, until the defeat at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

Suleiman's suspicion of Ibrahim was worsened by a quarrel between the latter and the Finance secretary (defterdar) Iskender Çelebi. The dispute ended in the disgrace of Çelebi on charges of intrigue, with Ibrahim convincing Suleiman to sentence the defterdar to death. Before his death however, Çelebi's last words were to accuse Ibrahim of conspiracy against the Sultan. These dying words convinced Suleiman of Ibrahim's disloyalty, and on 15 March 1536 Ibrahim was executed.

In the Indian Ocean, Suleiman led several naval campaigns against the Portuguese in an attempt to remove them and reestablish trade with India. Aden in Yemen was captured by the Ottomans in 1538, in order to provide an Ottoman base for raids against Portuguese possessions on the western coast of modern India and Pakistan. Sailing on to India, the Ottomans failed against the Portuguese at the Siege of Diu in September 1538, but then returned to Aden, where they fortified the city with 100 pieces of artillery. From this base, Sulayman Pasha managed to take control of the whole country of Yemen, also taking Sana'a. Aden rose against the Ottomans however and invited the Portuguese instead, so that the Portuguese were in control of the city until its seizure by Piri Reis in the Capture of Aden (1548).

By the 1540s a renewal of the conflict in Hungary presented Suleiman with the opportunity to avenge the defeat suffered at Vienna. In 1541 the Habsburgs attempted to lay siege to Buda but were repulsed, and more Habsburg fortresses were captured by the Ottomans in two consecutive campaigns in 1541 and 1544 as a result, Ferdinand and Charles were forced to conclude a humiliating five-year treaty with Suleiman. Ferdinand renounced his claim to the Kingdom of Hungary and was forced to pay a fixed yearly sum to the Sultan for the Hungarian lands he continued to control. Of more symbolic importance, the treaty referred to Charles V not as 'Emperor' but as the 'King of Spain', leading Suleiman to identify as the true 'Caesar'.

East of Morocco, huge Muslim territories in North Africa were annexed. The Barbary States of Tripolitania, Tunisia and Algeria became autonomous provinces of the Empire, serving as the leading edge of Suleiman's conflict with Charles V, whose attempt to drive out the Turks failed in 1541. The piracy carried on thereafter by the Barbary pirates of North Africa can be seen in the context of the wars against Spain.

In 1542, facing a Common Habsburg enemy, Francis I sought to renew the Franco-Ottoman alliance. As a result, Suleiman dispatched 100 galleys under Barbarossa to assist the French in the western Mediterranean. Barbarossa pillaged the coast of Naples and Sicily before reaching France, where Francis made Toulon the Ottoman admiral's naval headquarters. Barbarossa attacked and captured Nice in 1543. By 1544, a peace between Francis I and Charles V had put a temporary end to the alliance between France and the Ottoman Empire.

Suleiman himself was an accomplished poet, writing in Persian and Turkish under the takhallus (nom de plume) Muhibbi (Turkish language text" xml:lang="ota">محبی, "Lover"). Some of Suleiman's verses have become Turkish proverbs, such as the well-known Everyone aims at the same meaning, but many are the versions of the story. When his young son Mehmed died in 1543, he composed a moving chronogram to commemorate the year: Peerless among princes, my Sultan Mehmed. In addition to Suleiman's own work, many great talents enlivened the literary world during Suleiman's rule, including Fuzuli and Baki. The literary Historian E. J. W. Gibb observed that "at no time, even in Turkey, was greater encouragement given to poetry than during the reign of this Sultan". Suleiman's most famous verse is:

Attempting to defeat the Shah once and for all, Suleiman embarked upon a second campaign in 1548–1549. As in the previous attempt, Tahmasp avoided confrontation with the Ottoman army and instead chose to retreat, using scorched earth tactics in the process and exposing the Ottoman army to the harsh winter of the Caucasus. Suleiman abandoned the campaign with temporary Ottoman gains in Tabriz and the Urmia region, a lasting presence in the province of Van, control of the western half of Azerbaijan and some forts in Georgia.

Sultan Suleiman's two wives (Hürrem and Mahidevran) had borne him six sons, four of whom survived past the 1550s. They were Mustafa, Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir. Of these, the eldest, was not Hürrem Sultan's son, but rather Mahidevran Sultan's, and therefore preceded Hürrem's children in the order of succession. Hürrem was aware that should Mustafa become Sultan her own children would be strangled. Yet Mustafa was recognized as the most talented of all the brothers and was supported by Pargalı İbrahim Pasha, who was by this time Suleiman's Grand Vizier. The Austrian ambassador Busbecq would note "Suleiman has among his children a son called Mustafa, marvelously well educated and prudent and of an age to rule, since he is 24 or 25 years old; may God never allow a Barbary of such strength to come near us", going on to talk of Mustafa's "remarkable natural gifts". Hürrem is usually held at least partly responsible for the intrigues in nominating a successor. Although she was Suleiman's wife, she exercised no official public role. This did not, however, prevent Hürrem from wielding powerful political influence. Since the Empire lacked, until the reign of Ahmed I, any formal means of nominating a successor, successions usually involved the death of competing princes in order to avert civil unrest and rebellions. In attempting to avoid the execution of her sons, Hürrem used her influence to eliminate those who supported Mustafa's accession to the throne.

Thus in power struggles apparently instigated by Hürrem, Suleiman had Ibrahim murdered and replaced with her sympathetic son-in-law, Rüstem Pasha. By 1552, when the campaign against Persia had begun with Rüstem appointed commander-in-chief of the expedition, intrigues against Mustafa began. Rüstem sent one of Suleiman's most trusted men to report that since Suleiman was not at the head of the army, the Soldiers thought the time had come to put a younger Prince on the throne; at the same time he spread rumors that Mustafa had proved receptive to the idea. Angered by what he came to believe were Mustafa's plans to claim the throne, the following summer upon return from his campaign in Persia, Suleiman summoned him to his tent in the Ereğli valley, stating he would "be able to clear himself of the crimes he was accused of and would have nothing to fear if he came".

Suleiman gave particular attention to the plight of the rayas, Christian subjects who worked the land of the Sipahis. His Kanune Raya, or "Code of the Rayas", reformed the law governing levies and taxes to be paid by the rayas, raising their status above serfdom to the extent that Christian serfs would migrate to Turkish territories to benefit from the reforms. The Sultan also played a role in protecting the Jewish subjects of his empire for centuries to come. In late 1553 or 1554, on the suggestion of his favorite Doctor and dentist, the Spanish Jew Moses Hamon, the Sultan issued a firman (Turkish language text" xml:lang="ota">فرمان) formally denouncing blood libels against the Jews. Furthermore, Suleiman enacted new Criminal and police legislation, prescribing a set of fines for specific offenses, as well as reducing the instances requiring death or mutilation. In the area of taxation, taxes were levied on various goods and produce, including animals, mines, profits of trade, and import-export duties. In addition to taxes, officials who had fallen into disrepute were likely to have their land and property confiscated by the Sultan.

Cihangir is said to have died of grief a few months after the news of his half-brother's murder. The two surviving brothers, Selim and Bayezid, were given command in different parts of the empire. Within a few years, however, civil war broke out between the brothers, each supported by his loyal forces. With the aid of his father's army, Selim defeated Bayezid in Konya in 1559, leading the latter to seek refuge with the Safavids along with his four sons. Following diplomatic exchanges, the Sultan demanded from the Safavid Shah that Bayezid be either extradited or executed. In return for large amounts of gold, the Shah allowed a Turkish executioner to strangle Bayezid and his four sons in 1561, clearing the path for Selim's succession to the throne five years later.

In 1564, Suleiman received an embassy from Aceh (a sultanate on Sumatra, in modern Indonesia), requesting Ottoman support against the Portuguese. As a result, an Ottoman expedition to Aceh was launched, which was able to provide extensive military support to the Acehnese.

On 6 September 1566, Suleiman, who had set out from Constantinople to command an expedition to Hungary, died before an Ottoman victory at the Battle of Szigetvár in Hungary and the Grand Vizier kept his death secret during the retreat for the enthronement of Selim II. Just the night before the sickly Sultan died in his tent, two months before he would have turned 72. The sultan’s body was taken back to Istanbul to be buried, while his heart, liver, and some other organs were buried in Turbék, outside Szigetvár. A mausoleum was constructed above the burial site, and came to be regarded as a holy place and pilgrimage site. Within a decade a mosque and Sufi hospice were built near it, and the site was protected by a salaried garrison of several dozen men.

While Sultan Suleiman was known as "the Magnificent" in the West, he was always Kanuni Suleiman or "The Lawgiver" (Turkish language text" xml:lang="ota">قانونی) to his own Ottoman subjects. As the Historian Lord Kinross notes, "Not only was he a great military campaigner, a man of the sword, as his father and great-grandfather had been before him. He differed from them in the extent to which he was also a man of the pen. He was a great legislator, standing out in the eyes of his people as a high-minded sovereign and a magnanimous exponent of justice". The overriding law of the empire was the Shari'ah, or Sacred Law, which as the Divine law of Islam was outside of the Sultan's powers to change. Yet an area of distinct law known as the Kanuns (Turkish language text" xml:lang="ota">قانون, canonical legislation) was dependent on Suleiman's will alone, covering areas such as Criminal law, land tenure and taxation. He collected all the judgments that had been issued by the nine Ottoman Sultans who preceded him. After eliminating duplications and choosing between contradictory statements, he issued a single legal code, all the while being careful not to violate the basic laws of Islam. It was within this framework that Suleiman, supported by his Grand Mufti Ebussuud, sought to reform the legislation to adapt to a rapidly changing empire. When the Kanun laws attained their final form, the code of laws became known as the kanun‐i Osmani (Turkish language text" xml:lang="ota">قانون عثمانی), or the "Ottoman laws". Suleiman's legal code was to last more than three hundred years.

Suleiman was infatuated with Hürrem Sultan, a harem girl from Ruthenia, then part of Poland. Western diplomats, taking notice of the palace gossip about her, called her "Russelazie" or "Roxelana", referring to her Ruthenian origins. The daughter of an Orthodox priest, she was captured by Tatars from Crimea, sold as a slave in Constantinople, and eventually rose through the ranks of the Harem to become Suleiman's favorite. Breaking with two centuries of Ottoman tradition, a former concubine had thus become the legal wife of the Sultan, much to the astonishment of the observers in the palace and the city. He also allowed Hürrem Sultan to remain with him at court for the rest of her life, breaking another tradition—that when imperial heirs came of age, they would be sent along with the imperial concubine who bore them to govern remote provinces of the Empire, never to return unless their progeny succeeded to the throne.