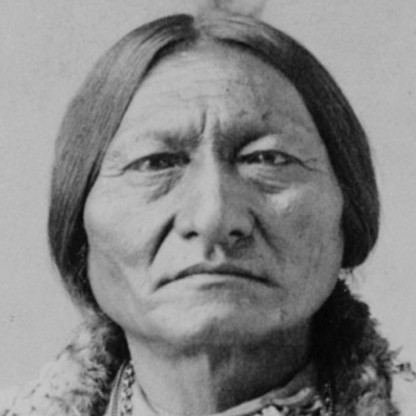

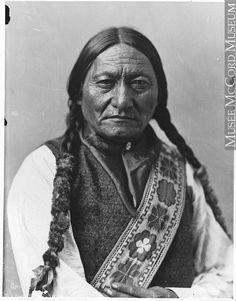

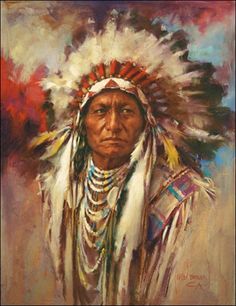

| Who is it? | Warrior |

| Birth Year | 1831 |

| Birth Place | Grand River, United States |

| Age | 188 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | (1890-12-15)December 15, 1890\n(aged 58–59)\nStanding Rock Indian Reservation\nGrand River, South Dakota |

| Resting place | Mobridge, South Dakota 45°31′0″N 100°29′7″W / 45.51667°N 100.48528°W / 45.51667; -100.48528Coordinates: 45°31′0″N 100°29′7″W / 45.51667°N 100.48528°W / 45.51667; -100.48528 |

| Spouse(s) | Light Hair Four Robes Snow-on-Her Seen-by-her-Nation Scarlet Woman |

| Relations | Spotted Elk (half brother) White Bull (nephew) Flying Hawk (nephew) Annie Oakley (symbolically "adopted" daughter) |

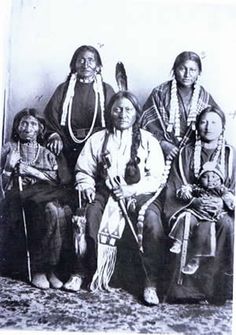

| Children | One Bull (adopted son) Crow Foot (son) Many Horses (daughter) Walks Looking (adopted daughter) |

| Parents | Jumping Bull (father) Her-Holy-Door (mother) |

| Battles/wars | Battle of the Little Bighorn |

Sitting Bull, also known as a prominent warrior in the United States, is estimated to have a net worth of $11 million in the year 2025. Born as Tatanka Yotanka, Sitting Bull was a revered leader and chief of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux tribe. He gained widespread recognition for his courageous efforts in defending his people's land and culture during the tumultuous period of American expansion in the late 19th century. Despite facing numerous challenges and conflicts, Sitting Bull's leadership and resilience left an indelible mark on history. Today, his net worth serves as a testament to his enduring legacy and impact.

At the climactic moment, "Sitting Bull intoned, 'The Great Spirit has given our enemies to us. We are to destroy them. We do not know who they are. They may be soldiers.' Ice too observed, 'No one then knew who the enemy were – of what tribe.'...They were soon to find out."(Utley 1992: 122–24)

After the 1848 finding of gold in the Sierra Nevada and dramatic gains in new wealth from it, other men became interested in the potential for gold mining in the Black Hills. In 1874, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition from Fort Abraham Lincoln near Bismarck, to explore the Black Hills for gold and to determine a suitable location for a military fort in the Hills. Custer's announcement of gold in the Black Hills triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush. Tensions increased between the Lakota and whites seeking to move into the Black Hills.

Based on tribal oral histories, Historian Margot Liberty theorizes many Lakota bands allied with the Cheyenne during the Plains Wars because they thought the other nation was under attack by the US. Given this connection, she suggests the major war should have been called "The Great Cheyenne War". Since 1860, the Northern Cheyenne had led several battles among the Plains Indians. Before 1876, the U.S. Army had destroyed seven Cheyenne camps, more than those of any other nation.

During the Dakota War of 1862, in which Sitting Bull's people were not involved, several bands of eastern Dakota people killed an estimated 300 to 800 settlers and Soldiers in south-central Minnesota in response to poor treatment by the government and in an effort to drive the whites away. Despite being embroiled in the American Civil War, the United States Army retaliated in 1863 and 1864, even against bands which had not been involved in the hostilities. In 1864, two brigades of about 2200 Soldiers under Brigadier General Alfred Sully attacked a village. The defenders were led by Sitting Bull, Gall and Inkpaduta. The Lakota and Dakota were driven out, but skirmishing continued into August.

The events of 1866–1868 mark a historically debated period of Sitting Bull's life. According to Historian Stanley Vestal, who conducted interviews with surviving Hunkpapa in 1930, Sitting Bull was made "Supreme Chief of the whole Sioux Nation" at this time. Later historians and ethnologists have refuted this concept of authority, as the Lakota society was highly decentralized. Lakota bands and their elders made individual decisions, including whether to wage war.

During the period 1868–1876, Sitting Bull developed into the most important of Native American political Leaders. After the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) and the creation of the Great Sioux Reservation, many traditional Sioux warriors, such as Red Cloud of the Oglala and Spotted Tail of the Brulé, moved to reside permanently on the reservations. They were largely dependent for subsistence on the US Indian agencies. Many other chiefs, including members of Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa band such as Gall, at times lived temporarily at the agencies. They needed the supplies at a time when white encroachment and the depletion of buffalo herds reduced their resources and challenged Native American independence.

In 1875, the Northern Cheyenne, Hunkpapa, Oglala, Sans Arc, and Minneconjou camped together for a Sun Dance, with both the Cheyenne Medicine man White Bull or Ice and Sitting Bull in association. This ceremonial alliance preceded their fighting together in 1876. Sitting Bull had a major revelation.

Custer’s 7th Cavalry advance party attacked Cheyenne and Lakota tribes at their camp on the Little Big Horn River (known as the Greasy Grass River to the Lakota) on June 25, 1876. The U.S. Army did not realize how large the camp was. More than 2,000 Native American warriors had left their reservations to follow Sitting Bull. Inspired by a vision of Sitting Bull’s, in which he saw U.S. Soldiers being killed as they entered the tribe’s camp, the Cheyenne and Lakota fought back. Custer's badly outnumbered troops lost ground quickly and were forced to retreat. The tribes led a counter-attack against the Soldiers on a nearby ridge, ultimately annihilating them.

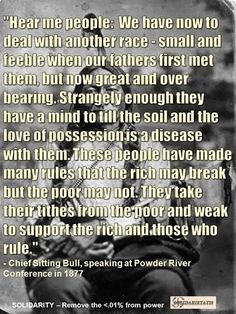

The Native Americans' victory celebrations were short-lived. Public shock and outrage at Custer's death and defeat, and the government's knowledge about the remaining Sioux, led them to assign thousands more Soldiers to the area. Over the next year, the new American military forces pursued the Lakota, forcing many of the Native Americans to surrender. Sitting Bull refused to surrender and in May 1877 led his band across the border into the North-West Territories, Canada. He remained in exile for four years near Wood Mountain, refusing a pardon and the chance to return. When crossing the border into Canadian territory, Sitting Bull was met by the Mounties of the region. During this meeting, James Morrow Walsh, commander of the North-West Mounted Police, explained to Sitting Bull that the Lakota were now on British soil and must obey British law. Walsh emphasized that he enforced the law equally and that every person in the territory had a right to justice. Walsh became an advocate for Sitting Bull and the two became good friends for the remainder of their lives.

Sitting Bull and his band of 186 people were kept separate from the other Hunkpapa gathered at the agency. Army officials were concerned that he would stir up trouble among the recently surrendered northern bands. On August 26, 1881, he was visited by census taker william T. Selwyn, who counted twelve people in the Hunkpapa leader's immediate family. Forty-one families, totaling 195 people, were recorded in Sitting Bull's band.

In 1883, rumors were reported that Sitting Bull had been baptized into the Catholic Church. James McLaughlin, Indian agent at Standing Rock Agency, dismissed these reports, saying that "The reported baptism of Sitting-Bull is erroneous. There is no immediate prospect of such ceremony so far as I am aware."

In 1884 show promoter Alvaren Allen asked Agent James McLaughlin to allow Sitting Bull to tour parts of Canada and the northern United States. The show was called the "Sitting Bull Connection." It was during this tour that Sitting Bull met Annie Oakley in Minnesota. He was so impressed with Oakley's skills with firearms that he offered $65 for a Photographer to take a photo of the two together. The admiration and respect was mutual. Oakley stated that Sitting Bull made a "great pet" of her. In observing Oakley, Sitting Bull's respect for the young sharpshooter grew. Oakley was quite modest in her attire, deeply respectful of others, and had a remarkable stage persona despite being a woman who stood only five feet in height. Sitting Bull felt that she was "gifted" by supernatural means in order to shoot so accurately with both hands. As a result of his esteem, he symbolically "adopted" her as a daughter in 1884. He named her "Little Sure Shot" – a name that Oakley used throughout her career.

In 1885, Sitting Bull was allowed to leave the reservation to go Wild Westing with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Buffalo Bill's Wild West. He earned about $50 a week for riding once around the arena, where he was a popular attraction. Although it is rumored that he cursed his audiences in his native tongue during the show, the Historian Utley contends that he did not. Historians have reported that Sitting Bull gave speeches about his Desire for education for the young, and reconciling relations between the Sioux and whites. The Historian Edward Lazarus wrote that Sitting Bull reportedly cursed his audience in Lakota in 1884, during an opening address celebrating the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway.

Sitting Bull returned to the Standing Rock Agency after working in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. Tension between Sitting Bull and Agent McLaughlin increased and each became more wary of the other over several issues including division and sale of parts of the Great Sioux Reservation. During that period, in 1889 Indian Rights Activist Caroline Weldon from Brooklyn, New York, a member of the National Indian Defense Association "NIDA", reached out to Sitting Bull, acting to be his voice, secretary, interpreter and advocate. She joined him, together with her young son Christy at his compound on the Grand River, sharing with him and his family home and hearth. A Paiute Indian, named Wovoka, spread a religious movement from Nevada eastward to the Plains in 1889 that preached a resurrection of the Native. This was a time of severe conditions of harsh winters and long droughts impacting the Sioux Reservation. It was known as the “Ghost Dance Movement”, because it called on the Indians to dance and chant for the rising up of deceased relatives and return of the buffalo. When the movement reached Standing Rock, Sitting Bull allowed the Dancers to gather at his camp. Although he did not appear to participate in the dancing, he was viewed as a key instigator. Alarm spread to nearby white settlements as the Sioux added a new feature to the dance – shirts that were said to stop bullets.

In 1890, James McLaughlin, the U.S. Indian Agent at Fort Yates on Standing Rock Agency, feared that the Lakota leader was about to flee the reservation with the Ghost Dancers, so he ordered the police to arrest him. On December 14, 1890, McLaughlin drafted a letter to Lt. Henry Bullhead (noted as Bull Head in lead), an Indian agency policeman, that included instructions and a plan to capture Sitting Bull. The plan called for the arrest to take place at dawn on December 15, and advised the use of a light spring wagon to facilitate removal before his followers could rally. Bullhead decided against using the wagon. He intended to have the police officers force Sitting Bull to mount a horse immediately after the arrest.

In 1953 Lakota family members exhumed what they believed to be Sitting Bull's remains, transporting them for reinterment near Mobridge, South Dakota, his birthplace. A monument to him was erected there.

Sitting Bull is a major character in Sharon Pollock's play "Walsh" (1973), in which he is depicted as a wise and tragic figure during the Lakota nation's time at Fort Walsh in Saskatchewan. The play is sympathetic to the character of Sitting Bull and hostile to the legend of George Armstrong Custer, re-presenting the General from the perspective of Native Americans as a butcher of women and children.

Sitting Bull was born on land later included in the Dakota Territory. In 2007, Sitting Bull's great-grandson asserted from family oral tradition that Sitting Bull was born along the Yellowstone River, south of present-day Miles City, Montana. He was named Jumping Badger at birth, and nicknamed Hunkesi, or "Slow," said to describe his careful and unhurried nature. When the boy was fourteen years old he accompanied a group of Lakota warriors (which included his father and his uncle Four Horns) in a raiding party to take horses from a camp of Crow warriors. Jumping Badger displayed bravery by riding forward and counting coup on one of the surprised Crow, which was witnessed by the other mounted Lakota. Upon returning to camp his father gave a celebratory feast at which he conferred his own name upon his son. The name, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake, which in the Lakota language means "Buffalo Bull Who Sits Down", would later be abbreviated to "Sitting Bull". Thereafter, Sitting Bull's father was known as Jumping Bull. At this ceremony before the entire band, Sitting Bull's father presented his son with an eagle feather to wear in his hair, a warrior's horse, and a hardened buffalo hide shield to mark his son's passage into manhood as a Lakota warrior.

While in Canada, Sitting Bull also met with Crowfoot, who was a leader of the Blackfeet, long-time powerful enemies of the Lakota and Cheyenne. Sitting Bull wished to make peace with the Blackfeet Nation and Crowfoot. As an advocate for peace himself, Crowfoot eagerly accepted the tobacco peace offering. Sitting Bull was so impressed by Crowfoot that he named one of his sons after him. Sitting Bull and his people stayed in Canada for 4 years. Due to the smaller size of the buffalo herds in Canada, Sitting Bull and his men found it difficult to find enough food to feed his people, who were starving and exhausted. Sitting Bull’s presence in the country led to increased tensions between the Canadian and the United States governments. Before Sitting Bull left Canada, he may have visited Walsh for a final time and left a ceremonial headdress as a memento.