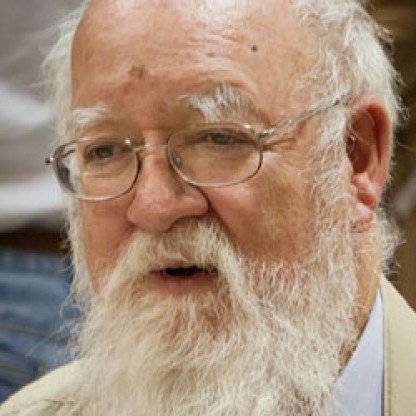

| Who is it? | Philosopher, social reformer, architect and esotericist |

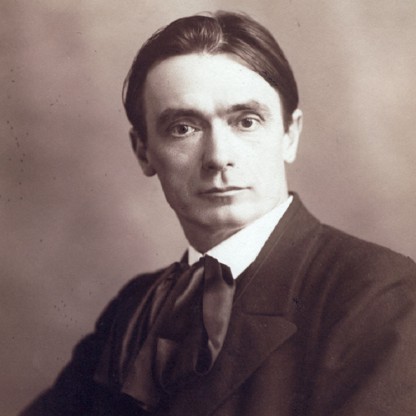

| Birth Year | 1861 |

| Birth Place | Donji Kraljevec, Croatia, Croatian |

| Age | 158 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 30 March 1925 (aged 64)\nDornach, Switzerland |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Alma mater | Vienna Institute of Technology University of Rostock (PhD, 1891) |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Eunicke (1899-1911) Marie Steiner-von Sivers (1914-1925) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Monism Holism in science Goethean science Anthroposophy |

| Main interests | Metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of science, esotericism, Christianity |

| Notable ideas | Anthroposophy, anthroposophical medicine, biodynamic agriculture, eurythmy, spiritual science, Waldorf education, holism in science |

Rudolf Steiner, a renowned Croatian philosopher, social reformer, architect, and esotericist, is estimated to have a net worth of $1.6 million in 2025. Steiner's contributions and expertise in various fields have propelled him to notable success and garnered him financial prosperity. With his wealth, he continues to make significant strides in his pursuits, leaving a lasting impact on the world through his innovative ideas and influential work.

The well-being of a community of people working together will be the greater, the less the individual claims for himself the proceeds of his work, i.e. the more of these proceeds he makes over to his fellow-workers, the more his own needs are satisfied, not out of his own work but out of the work done by others.

— Steiner, The Fundamental Social Law

Steiner's father, Johann(es) Steiner (1829 – 1910), left a position as a gamekeeper in the Service of Count Hoyos in Geras, northeast Lower Austria to marry one of the Hoyos family's housemaids, Franziska Blie (1834 Horn – 1918, Horn), a marriage for which the Count had refused his permission. Johann became a telegraph operator on the Southern Austrian Railway, and at the time of Rudolf's birth was stationed in Kraljevec in the Muraköz region of the Austrian Empire (present-day Donji Kraljevec in the Međimurje region of northernmost Croatia). In the first two years of Rudolf's life, the family moved twice, first to Mödling, near Vienna, and then, through the promotion of his father to stationmaster, to Pottschach, located in the foothills of the eastern Austrian Alps in Lower Austria.

Steiner entered the village school; following a disagreement between his father and the schoolmaster, he was briefly educated at home. In 1869, when Steiner was eight years old, the family moved to the village of Neudörfl and in October 1872 Steiner proceeded from the village school there to the realschule in Wiener Neustadt.

In 1879, the family moved to Inzersdorf to enable Steiner to attend the Vienna Institute of Technology, where he studied mathematics, physics, chemistry, botany, biology, literature, and philosophy on an academic scholarship from 1879 to 1883, at the end of which time he withdrew from the institute without graduating. In 1882, one of Steiner's teachers, Karl Julius Schröer, suggested Steiner's name to Joseph Kürschner, chief Editor of a new edition of Goethe's works, who asked Steiner to become the edition's natural science Editor, a truly astonishing opportunity for a young student without any form of academic credentials or previous publications.

In his commentaries on Goethe's scientific works, written between 1884 and 1897, Steiner presented Goethe's approach to science as essentially phenomenological in nature, rather than theory- or model-based. He developed this conception further in several books, The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception (1886) and Goethe's Conception of the World (1897), particularly emphasizing the transformation in Goethe's approach from the physical sciences, where experiment played the primary role, to plant biology, where both accurate perception and imagination were required to find the biological archetypes (Urpflanze), and postulated that Goethe had sought but been unable to fully find the further transformation in scientific thinking necessary to properly interpret and understand the animal kingdom. Steiner emphasized the role of evolutionary thinking in Goethe's discovery of the intermaxillary bone in human beings; Goethe expected human anatomy to be an evolutionary transformation of animal anatomy.

In 1888, as a result of his work for the Kürschner edition of Goethe's works, Steiner was invited to work as an Editor at the Goethe archives in Weimar. Steiner remained with the archive until 1896. As well as the introductions for and commentaries to four volumes of Goethe's scientific writings, Steiner wrote two books about Goethe's philosophy: The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception (1886), which Steiner regarded as the epistemological foundation and justification for his later work, and Goethe's Conception of the World (1897). During this time he also collaborated in complete editions of the works of Arthur Schopenhauer and the Writer Jean Paul and wrote numerous articles for various journals.

In 1891, Steiner received a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Rostock, for his dissertation discussing Fichte's concept of the ego, submitted to Heinrich von Stein, whose Seven Books of Platonism Steiner esteemed. Steiner's dissertation was later published in expanded form as Truth and Knowledge: Prelude to a Philosophy of Freedom (German: Wahrheit und Wissenschaft – Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Freiheit), with a dedication to Eduard von Hartmann. Two years later, he published Die Philosophie der Freiheit (The Philosophy of Freedom or The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity—Steiner's preferred English title) (1894), an exploration of epistemology and ethics that suggested a way for humans to become spiritually free beings. Steiner later spoke of this book as containing implicitly, in philosophical form, the entire content of what he later developed explicitly as anthroposophy.

Steiner approached the philosophical questions of knowledge and freedom in two stages. In his dissertation, published in expanded form in 1892 as Truth and Knowledge, Steiner suggests that there is an inconsistency between Kant's philosophy, which posits that all knowledge is a representation of an essential verity inaccessible to human consciousness, and modern science, which assumes that all influences can be found in the sensory and mental world to which we have access. Steiner considered Kant's philosophy of an inaccessible beyond ("Jenseits-Philosophy") a stumbling block in achieving a satisfying philosophical viewpoint.

In 1896, Steiner declined an offer from Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche to help organize the Nietzsche archive in Naumburg. Her brother by that time was non compos mentis. Förster-Nietzsche introduced Steiner into the presence of the catatonic philosopher; Steiner, deeply moved, subsequently wrote the book Friedrich Nietzsche, Fighter for Freedom. Steiner later related that:

In 1897, Steiner left the Weimar archives and moved to Berlin. He became part owner of, chief Editor of, and an active contributor to the literary journal Magazin für Literatur, where he hoped to find a readership sympathetic to his philosophy. Many subscribers were alienated by Steiner's unpopular support of Émile Zola in the Dreyfus Affair and the journal lost more subscribers when Steiner published extracts from his correspondence with anarchist John Henry Mackay. Dissatisfaction with his editorial style eventually led to his departure from the magazine.

In 1899 Steiner experienced what he described as a life-transforming inner encounter with the being of Christ; previously he had little or no relation to Christianity in any form. Then and thereafter, his relationship to Christianity remained entirely founded upon personal experience, and thus both non-denominational and strikingly different from conventional religious forms. Steiner was then 38, and the experience of meeting the Christ occurred after a tremendous inner struggle. To use Steiner's own words, the "experience culminated in my standing in the spiritual presence of the Mystery of Golgotha in a most profound and solemn festival of knowledge."

In his earliest works, Steiner already spoke of the "natural and spiritual worlds" as a unity. From 1900 on, he began lecturing about concrete details of the spiritual world(s), culminating in the publication in 1904 of the first of several systematic presentations, his Theosophy: An Introduction to the Spiritual Processes in Human Life and in the Cosmos. As a starting point for the book Steiner took a quotation from Goethe, describing the method of natural scientific observation, while in the Preface he made clear that the line of thought taken in this book led to the same goal as that in his earlier work, The Philosophy of Freedom.

In the years 1903–1908 Steiner maintained the magazine "Lucifer-Gnosis" and published in it essays on topics such as initiation, reincarnation and karma, and knowledge of the supernatural world. Some of these were later collected and published as books, such as How to Know Higher Worlds (1904/5) and Cosmic Memory. The book An Outline of Esoteric Science was published in 1910. Important themes include:

As a young man, Steiner was a private tutor and a lecturer on history for the Berlin Arbeiterbildungsschule, an educational initiative for working class adults. Soon thereafter, he began to articulate his ideas on education in public lectures, culminating in a 1907 essay on The Education of the Child in which he described the major phases of child development which formed the foundation of his approach to education. His conception of education was influenced by the Herbartian pedagogy prominent in Europe during the late nineteenth century, though Steiner criticized Herbart for not sufficiently recognizing the importance of educating the will and feelings as well as the intellect.

Steiner wrote four mystery plays between 1909 and 1913: The Portal of Initiation, The Souls' Probation, The Guardian of the Threshold and The Soul's Awakening, modeled on the esoteric dramas of Edouard Schuré, Maurice Maeterlinck, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Steiner's plays continue to be performed by anthroposophical groups in various countries, most notably (in the original German) in Dornach, Switzerland and (in English translation) in Spring Valley, New York and in Stroud and Stourbridge in the U.K.

From the late 1910s, Steiner was working with doctors to create a new approach to Medicine. In 1921, pharmacists and Physicians gathered under Steiner's guidance to create a pharmaceutical company called Weleda which now distributes natural medical products worldwide. At around the same time, Dr. Ita Wegman founded a first anthroposophic medical clinic (now the Ita Wegman Clinic) in Arlesheim.

In contrast to mainstream Theosophy, Steiner sought to build a Western approach to spirituality based on the philosophical and mystical traditions of European culture. The German Section of the Theosophical Society grew rapidly under Steiner's leadership as he lectured throughout much of Europe on his spiritual science. During this period, Steiner maintained an original approach, replacing Madame Blavatsky's terminology with his own, and basing his spiritual research and teachings upon the Western esoteric and philosophical tradition. This and other differences, in particular Steiner's vocal rejection of Leadbeater and Besant's claim that Jiddu Krishnamurti was the vehicle of a new Maitreya, or world Teacher, led to a formal split in 1912/13, when Steiner and the majority of members of the German section of the Theosophical Society broke off to form a new group, the Anthroposophical Society. (Steiner took the name "Anthroposophy" from the title of a work of the Austrian Philosopher Robert von Zimmermann, published in Vienna in 1856.)

The Anthroposophical Society grew rapidly. Fueled by a need to find an artistic home for their yearly conferences, which included performances of plays written by Edouard Schuré and Steiner, the decision was made to build a theater and organizational center. In 1913, construction began on the first Goetheanum building, in Dornach, Switzerland. The building, designed by Steiner, was built to a significant part by volunteers who offered craftsmanship or simply a will to learn new skills. Once World War I started in 1914, the Goetheanum volunteers could hear the sound of cannon fire beyond the Swiss border, but despite the war, people from all over Europe worked peaceably side by side on the building's construction.

In 1919, Emil Molt invited him to lecture to his workers at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart. Out of these lectures came a new school, the Waldorf school. In 1922, Steiner presented these ideas at a conference called for this purpose in Oxford by Professor Millicent Mackenzie. This conference led to the founding of the first Waldorf schools in Britain. During Steiner's lifetime, schools based on his educational principles were also founded in Hamburg, Essen, The Hague and London; there are now more than 1000 Waldorf schools worldwide.

In the 1920s, Steiner was approached by Friedrich Rittelmeyer, a Lutheran pastor with a congregation in Berlin, who asked if it was possible to create a more modern form of Christianity. Soon others joined Rittelmeyer – mostly Protestant Pastors and theology students, but including several Roman Catholic Priests. Steiner offered counsel on renewing the spiritual potency of the sacraments while emphasizing freedom of thought and a personal relationship to religious life. He envisioned a new synthesis of Catholic and Protestant approaches to religious life, terming this "modern, Johannine Christianity".

His primary sculptural work is The Representative of Humanity (1922), a nine-meter high wood sculpture executed as a joint project with the Sculptor Edith Maryon. This was intended to be placed in the first Goetheanum. It shows a central, free-standing Christ holding a balance between the beings of Lucifer and Ahriman, representing opposing tendencies of expansion and contraction. It was intended to show, in conscious contrast to Michelangelo's Last Judgment, Christ as mute and impersonal such that the beings that approach him must judge themselves. The sculpture is now on permanent display at the Goetheanum.

From 1923 on, Steiner showed signs of increasing frailness and illness. He nonetheless continued to lecture widely, and even to travel; especially towards the end of this time, he was often giving two, three or even four lectures daily for courses taking place concurrently. Many of these lectures focused on practical areas of life such as education.

In collaboration with Marie von Sivers, Steiner also founded a new approach to acting, storytelling, and the recitation of poetry. His last public lecture course, given in 1924, was on speech and drama. The Russian actor, Director, and acting coach Michael Chekhov based significant aspects of his method of acting on Steiner's work.

Increasingly ill, he held his last lecture in late September, 1924. He continued work on his autobiography during the last months of his life; he died on 30 March 1925.

The 150th anniversary of Rudolf Steiner's birth was marked by the first major retrospective exhibition of his art and work, 'Kosmos - Alchemy of the everyday'. Organized by Vitra Design Museum, the traveling exhibition presented many facets of Steiner's life and achievements, including his influence on architecture, furniture design, dance (Eurythmy), education, and agriculture (Biodynamic agriculture). The exhibition opened in 2011 at the Kunstmuseum in Stuttgart, Germany,

Robert Todd Carroll has said of Steiner that "Some of his ideas on education – such as educating the handicapped in the mainstream – are worth considering, although his overall plan for developing the spirit and the soul rather than the intellect cannot be admired". Steiner's translators have pointed out that his use of Geist includes both mind and spirit, however, as the German term Geist can be translated equally properly in either way.

Steiner's work includes both universalist, humanist elements and historically influenced racial assumptions. Due to the contrast and even contradictions between these elements, "whether a given reader interprets Anthroposophy as racist or not depends upon that reader's concerns". Steiner considered that by dint of its shared language and culture, each people has a unique essence, which he called its soul or spirit. He saw race as a physical manifestation of humanity's spiritual evolution, and at times discussed race in terms of complex hierarchies that were largely derived from 19th century biology, anthropology, philosophy and Theosophy. However, he consistently and explicitly subordinated race, ethnicity, gender, and indeed all hereditary factors, to individual factors in development. For Steiner, human individuality is centered in a person's unique biography, and he believed that an individual's experiences and development are not bound by a single lifetime or the qualities of the physical body. More specifically: