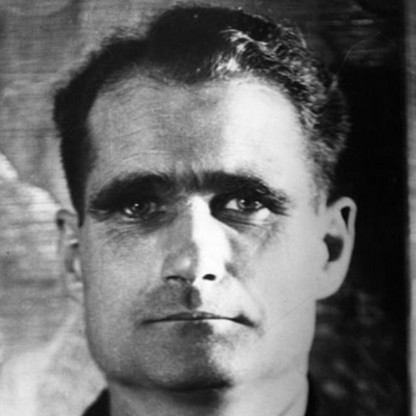

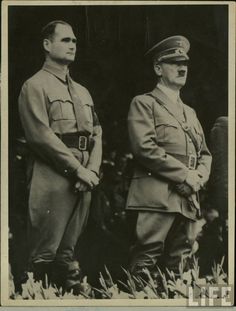

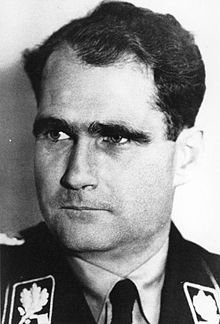

On 30 January 1933, Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor, his first step in gaining dictatorial control of Germany. Hess was named Deputy Führer of the NSDAP on 21 April and was appointed to the cabinet, with the post of Reich Minister without Portfolio, on 1 December. With offices in the Brown House in Munich and another in Berlin, Hess was responsible for several departments, including foreign affairs, Finance, health, education and law. All legislation passed through his office for approval, except that concerning the army, the police and foreign policy, and he wrote and co-signed many of Hitler's decrees. An organiser of the annual Nuremberg Rallies, he usually gave the opening speech and introduced Hitler. Hess also spoke over the radio and at rallies around the country, so frequently that the speeches were collected into book form in 1938. Hess acted as Hitler's delegate in negotiations with industrialists and members of the wealthier classes. As Hess had been born abroad, Hitler had him oversee the NSDAP groups such as the NSDAP/AO that were in charge of party members living in other countries. Hitler instructed Hess to review all court decisions that related to persons deemed enemies of the Party. He was authorised to increase the sentences of anyone he felt got off too lightly in these cases, and was also empowered to take "merciless action" if he saw fit to do so. This often entailed sending the person to a concentration camp or simply ordering the person killed. Hess was given the rank of Obergruppenführer in the Schutzstaffel (SS) in 1934, the second-highest SS rank.