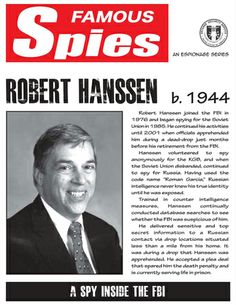

| Who is it? | Former FBI Agent & Spy for the Soviet Union |

| Birth Day | April 18, 1944 |

| Birth Place | Chicago, United States |

| Age | 79 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Other names | Ramon Garcia, Jim Baker, G. Robertson, Graysuit, "B" |

| Occupation | Former FBI agent and spy for the Soviet Union and later the Russian Federation |

| Criminal charge | 18 U.S.C. § 794(a) and 794(c) (Espionage Act) |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment (without parole) |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated at ADX Florence |

| Spouse(s) | Bernadette "Bonnie" Wauck Hanssen |

| Parent(s) | Howard Hanssen (father) Vivian Hanssen (mother) |

| Allegiance | Soviet Union |

Robert Hanssen, a former FBI agent notorious for spying on the United States on behalf of the Soviet Union, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2025. Hanssen's actions shocked the nation when they were discovered, as he had held a prominent position within the FBI while simultaneously betraying his country. His espionage activities spanned over two decades, during which he provided classified information to the Soviets. Hanssen was eventually apprehended and sentenced to life imprisonment. Despite the notoriety surrounding his name, his net worth remains relatively modest, reflecting the consequences of his actions.

Hanssen was born in Chicago, Illinois, to a family who lived in the Norwood Park community. His father Howard, a Chicago police officer, was emotionally abusive to Hanssen during his childhood. He graduated from william Howard Taft High School in 1962 and went on to attend Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, where he earned a bachelor's degree in chemistry in 1966.

Hanssen met Bernadette "Bonnie" Wauck, a staunch Roman Catholic, while attending dental school at Northwestern. The couple married in 1968, and Hanssen converted from Lutheranism to his wife's Catholicism, becoming a fervent believer and being extensively involved in the conservative Catholic organization Opus Dei.

Hanssen applied for a cryptographer position in the National Security Agency, but was rebuffed due to budget setbacks. He enrolled in dental school at Northwestern University but switched his focus to Business after three years. Hanssen received an MBA in accounting and information systems in 1971 and took a job with an accounting firm. He quit after one year and joined the Chicago Police Department as an internal affairs investigator, specializing in forensic accounting. In January 1976, he left the police department to join the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Upon becoming a special agent on January 12, 1976, Hanssen was transferred to the FBI's Gary, Indiana, field office. In 1978, Hanssen and his growing family (of three children and eventually six) moved to New York City when the FBI transferred him to its field office there. The next year, Hanssen was moved into counter-intelligence and given the task of compiling a database of Soviet intelligence for the Bureau.

Later that year, Hanssen handed over extensive information about American planning for Measurement and Signature Intelligence (MASINT), an umbrella term for intelligence collected by a wide array of electronic means, such as radar, spy satellites, and signal intercepts. When the Soviets began construction on a new embassy in 1977, the FBI dug a tunnel beneath their decoding room. The FBI planned to use it for eavesdropping, but never did for fear of being caught. Hanssen disclosed this detailed information to the Soviets in September 1989 and received a US$55,000 payment the next month. On two occasions, Hanssen gave the Soviets a complete list of American double agents.

In 1979, only three years after joining the FBI, Hanssen approached the Soviet GRU and offered his services. He never indicated any political or ideological motive for his actions, telling the FBI after he was caught that his only motivation was profit. During his first espionage cycle, Hanssen told the GRU a significant amount, including information on the FBI's bugging activities and lists of suspected Soviet intelligence agents. His most important leak was the betrayal of Dmitri Polyakov, a CIA informant who passed enormous amounts of information to American intelligence while he rose to the rank of General in the Soviet Army. For unknown reasons, the Soviets did not act against Polyakov until he was betrayed a second time by CIA mole Aldrich Ames in 1985. Polyakov was arrested in 1986 and executed in 1988. Ames was officially blamed for giving Polyakov's name to the Soviets, while Hanssen's attempt was not revealed until after his 2001 capture.

In 1981, Hanssen was transferred to FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C. and moved to the suburb of Vienna, Virginia. His new job in the FBI's budget office gave him access to information involving many different FBI operations. This included all the FBI activities related to wiretapping and electronic surveillance, which were Hanssen's responsibility. He became known in the Bureau as an expert on computers.

On October 1, 1985, Hanssen sent an anonymous letter to the KGB offering his services and asking for US$100,000 in cash. In the letter, he gave the names of three KGB agents secretly working for the FBI: Boris Yuzhin, Valery Martynov and Sergei Motorin. Although Hanssen was unaware of it, all three agents had already been exposed earlier that year by Ames. Martynov, Motorin and Yuzhin were recalled to Moscow, where they were arrested, charged, tried and convicted of espionage against the USSR. Martynov and Motorin were condemned to death and executed via a gun-shot to the back of the head. Yuzhin was imprisoned for six years before he was released under a general amnesty to political prisoners, and subsequently emigrated to the U.S. Because the FBI blamed Ames for the leak, Hanssen was not suspected nor investigated. The October 1 letter was the beginning of a long, active espionage period for Hanssen.

FBI investigators later made progress during an operation in which they paid off disaffected Russian intelligence officers to deliver information on moles. They found and paid $7 million to a KGB agent with access to a file on "B." While it did not contain Hanssen's name, among the information was an audiotape of a July 21, 1986, conversation between "B" and KGB agent Aleksander Fefelov. FBI agent Michael Waguespack felt the voice was familiar, but could not remember who it was. Rifling through the rest of the files, they found notes of the mole using a quote from General George S. Patton about "the purple-pissing Japanese." FBI analyst Bob King remembered Hanssen using that same quote. Waguespack listened to the tape again and recognized the voice as belonging to Hanssen. With the mole finally identified, locations, dates and cases were matched with Hanssen's activities during the time period. Two fingerprints collected from a trash bag in the file were analyzed and proved to be Hanssen's.

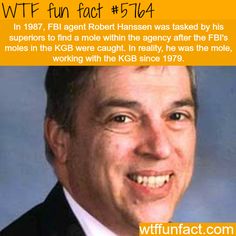

Hanssen was recalled yet again to Washington in 1987. He was given the task of making a study of all known and rumored penetrations of the FBI in order to find the man who had betrayed Martynov and Motorin; this meant that he was looking for himself. Hanssen ensured that he did not unmask himself with his study, but in addition, he turned over the entire study—including the list of all Soviets who had contacted the FBI about FBI moles—to the KGB in 1988. That same year, Hanssen, according to a government report, "committed a serious security breach" by revealing secret information to a Soviet defector during a debriefing. The agents working underneath him reported this breach to a supervisor, but no action was taken.

In 1989, Hanssen compromised the FBI investigation of Felix Bloch, a State Department official who had come under suspicion for espionage. Hanssen warned that Bloch was under investigation, causing the KGB to abruptly break off contact with Bloch. The FBI was unable to produce any hard evidence, and as a result, Bloch was never charged with a crime, although the State Department later terminated his employment and denied his pension. The failure of the Bloch investigation, and the FBI's investigation of how the KGB found out they were investigating Bloch, drove the mole hunt that eventually led to the arrest of Hanssen.

In 1990, Hanssen's brother-in-law, Mark Wauck, who was also an FBI employee, recommended to the Bureau that Hanssen be investigated for espionage; this came after Bonnie Hanssen's sister Jeanne Beglis had found a pile of cash sitting on a dresser in the Hanssens' house. Bonnie had previously told her brother that Hanssen once talked about retiring in Poland, then part of the Eastern Bloc. Wauck also knew that the FBI was hunting for a mole and so spoke with his supervisor, who took no action.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, Hanssen, possibly worried that he could be exposed during the ensuing political upheaval, broke off communications with his handlers for a time. The following year, after the Russian Federation took over the demised USSR's spy agencies, Hanssen made a risky approach to the GRU, with whom he had not been in contact in ten years. He went in person to the Russian embassy and physically approached a GRU officer in the parking garage. Hanssen, carrying a package of documents, identified himself by his Soviet code name, "Ramon Garcia," and described himself as a "disaffected FBI agent" who was offering his services as a spy. The Russian officer, who evidently did not recognize the code name, drove off. The Russians then filed an official protest with the State Department, believing Hanssen to be a triple agent. Despite having shown his face, disclosed his code name, and revealed his FBI affiliation, Hanssen escaped arrest when the Bureau's investigation into the incident did not advance.

Hanssen never told the KGB or GRU his identity and refused to meet them personally, with the exception of the abortive 1993 contact in the Russian embassy parking garage. The FBI believes the Russians never knew the name of their source. Going by the alias "Ramon" or "Ramon Garcia," Hanssen exchanged intelligence and payments through an old-fashioned dead drop system in which he and his KGB handlers would leave packages in public, unobtrusive places. He refused to use the dead drop sites that his handler, Victor Cherkashin, suggested and instead picked his own. He also designated a code to be used when dates were exchanged. Six was to be added to the month, day, and time of a designated drop time, so that, for Example, a drop scheduled for January 6 at 1 pm would be written as July 12 at 7 pm.

The FBI and CIA formed a joint mole-hunting team in 1994 to find the suspected second intelligence leak. They formed a list of all agents known to have access to cases that were compromised. The FBI's codename for the suspected spy was "Graysuit." Some promising suspects were cleared, and the mole hunt found other penetrations such as CIA officer Harold James Nicholson. But Hanssen escaped notice.

By 1998, using FBI Criminal profiling techniques, the pursuers zeroed in on an innocent man: Brian Kelley, a CIA operative involved in the Bloch investigation. The CIA and FBI searched his house, tapped his phone and put him under surveillance, following him and his family everywhere. In November 1998, they had a man with a foreign accent come to Kelley's door, warn him that the FBI knew he was a spy and tell him to show up at a Metro station the next day in order to escape. Kelley instead reported the incident to the FBI. In 1999, the FBI even interrogated Kelley, his ex-wife, two sisters and three children. All denied everything. He was eventually placed on administrative leave, where he remained falsely accused until after Hanssen was arrested.

During the same time period, Hanssen would search the FBI's internal computer case record to see if he was under investigation. He was indiscreet enough to type his own name into FBI search engines. Finding nothing, Hanssen decided to resume his spy career after eight years without contact with the Russians. He established contact with the SVR (the successor to the Soviet-era KGB) in the fall of 1999. He continued to perform highly incriminating searches of FBI files for his own name and address.

The FBI placed Hanssen under surveillance and soon discovered that he was again in contact with the Russians. In order to bring him back to FBI headquarters, where he could be closely monitored and kept away from sensitive data, they promoted him in December 2000 and gave him a new job supervising FBI computer security. In January 2001, Hanssen was given an office and an assistant, Eric O'Neill, who in reality was a young FBI agent who had been assigned to watch Hanssen. O'Neill ascertained that Hanssen was using a Palm III PDA to store his information. When O'Neill was able to briefly obtain Hanssen's PDA and have agents download and decode its encrypted contents, the FBI had its "smoking gun."

With the representation of Washington Lawyer Plato Cacheris, Hanssen negotiated a plea bargain that enabled him to escape the death penalty in exchange for cooperating with authorities. On July 6, 2001, he pleaded guilty to 14 counts of espionage and one of conspirary to commit espionage in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. On May 10, 2002, he was sentenced to fifteen consecutive sentences of life in prison without the possibility of parole. "I apologize for my behavior. I am shamed by it," Hanssen told U.S. District Judge Claude Hilton. "I have opened the door for calumny against my totally innocent wife and children. I have hurt so many deeply."

The 2007 documentary Superspy: The Man Who Betrayed the West describes the hunt to trap Robert Hanssen. Hanssen also was the subject of a 2002 made-for-television movie, Master Spy: The Robert Hanssen Story, with the teleplay by Norman Mailer and starring william Hurt as Hanssen. Robert Hanssen's jailers allowed him to watch this movie but Hanssen was so angered by the film that he turned it off.

Despite these efforts at caution and security, he could at times be reckless. He once said in a letter to the KGB that it should emulate the management style of Mayor of Chicago Richard J. Daley – a comment that easily could have led an investigator to look at people from Chicago. He took the risk of recommending to his handlers that they try to recruit his closest friend, a colonel in the United States Army. In an early letter to Cherkashin, he claims, "As far as the funds are concerned, I have little need or utility for more than the $100,000."

The existence of two Russian moles working in the U.S. security and intelligence establishment simultaneously—Ames at the CIA and Hanssen at the FBI—complicated counterintelligence efforts in the 1990s. Ames was arrested in 1994; his exposure explained many of the asset losses American intelligence suffered in the 1980s, including the arrest and execution of Martynov and Motorin. However, two cases—the Bloch investigation and the embassy tunnel—stood out and remained unsolved. Ames had been stationed in Rome at the time of the Bloch investigation, and could not have had knowledge of that case or of the tunnel under the embassy, as he did not work for the FBI.