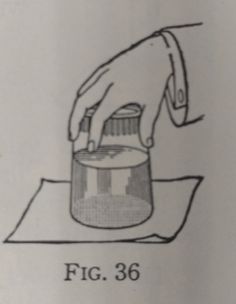

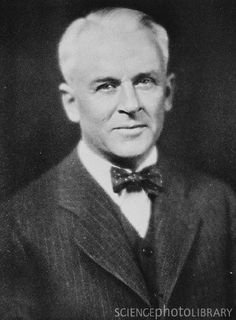

When Einstein published his seminal 1905 paper on the particle theory of light, Millikan was convinced that it had to be wrong, because of the vast body of evidence that had already shown that light was a wave. He undertook a decade-long experimental program to test Einstein's theory, which required building what he described as "a machine shop in vacuo" in order to prepare the very clean metal surface of the photo electrode. His results published in 1914 confirmed Einstein's predictions in every detail, but Millikan was not convinced of Einstein's interpretation, and as late as 1916 he wrote, "Einstein's photoelectric equation... cannot in my judgment be looked upon at present as resting upon any sort of a satisfactory theoretical foundation," even though "it actually represents very accurately the behavior" of the photoelectric effect. In his 1950 autobiography, however, he simply declared that his work "scarcely permits of any other interpretation than that which Einstein had originally suggested, namely that of the semi-corpuscular or photon theory of light itself".