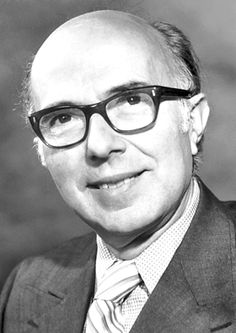

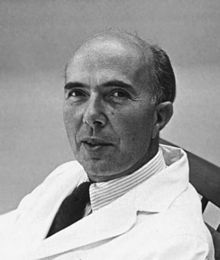

| Who is it? | Virologist |

| Birth Day | February 22, 1914 |

| Birth Place | Italy, American |

| Age | 106 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | February 19, 2012(2012-02-19) (aged 97)\nLa Jolla, California |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Residence | Imperia, Milan, La Jolla |

| Alma mater | University of Turin |

| Known for | Reverse transcriptase |

| Awards | Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research (1964) Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize (1973) Selman A. Waksman Award (1974) ForMemRS (1974) Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1975) |

| Fields | Virologist |

| Institutions | Indiana University Bloomington California Institute of Technology Salk Institute London Research Institute |

| Doctoral students | Howard Temin |

Renato Dulbecco, a renowned virologist in America, is expected to have a net worth of $15 million by 2025. Widely recognized for his groundbreaking research on viruses, Dulbecco has made substantial contributions to the field of virology and has earned numerous accolades throughout his distinguished career. From his pioneering work on the interaction between animal cells and viruses to his formulation of the plaque assay technique, Dulbecco's scientific breakthroughs have had significant implications in the study of infectious diseases. Alongside his scientific achievements, Dulbecco's net worth is attributed to his successful collaborations, patent rights, and royalties from his work. As one of the key figures in virology, Dulbecco's net worth reflects not only his professional accomplishments but also the profound impact of his research in advancing our understanding of viruses and their role in human health.

Dulbecco was born in Catanzaro (Southern Italy), but spent his childhood and grew up in Liguria, in the coastal city Imperia. He graduated from high school at 16, then moved to the University of Turin. Despite a strong interest for mathematics and physics, he decided to study Medicine. At only 22, he graduated in morbid anatomy and pathology under the supervision of professor Giuseppe Levi. During these years he met Salvador Luria and Rita Levi-Montalcini, whose friendship and encouragement would later bring him to the United States. In 1936 he was called up for military Service as a medical officer, and later (1938) discharged. In 1940 Italy entered World War II and Dulbecco was recalled and sent to the front in France and Russia, where he was wounded. After hospitalization and the collapse of Fascism, he joined the resistance against the German occupation.

After the war he resumed his work at Levi's laboratory, but soon he moved, together with Levi-Montalcini, to the U.S., where, at Indiana University, he worked with Salvador Luria on bacteriophages. In the summer of 1949 he moved to Caltech, joining Max Delbrück's group (see Phage group). There he started his studies about animal oncoviruses, especially of polyoma family. In the late 1950s, he took Howard Temin as a student, with whom, and together with David Baltimore, he would later share the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for "their discoveries concerning the interaction between tumour viruses and the genetic material of the cell." Temin and Baltimore arrived at the discovery of reverse transcriptase simultaneously and independently from each other; although Dulbecco did not take direct part in either of their experiments, he had taught the two methods they used to make the discovery.

Throughout this time he also worked with Marguerite Vogt. In 1962, he moved to the Salk Institute and then in 1972 to The Imperial Cancer Research Fund (now named the Cancer Research UK London Research Institute). In 1986 he was among the Scientists who launched the Human Genome Project. From 1993 to 1997 he moved back to Italy, where he was President of the Institute of Biomedical Technologies at C.N.R. (National Council of Research) in Milan. He also retained his position on the faculty of Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Dulbecco was actively involved in research into identification and characterization of mammary gland cancer stem cells until December 2011. His research using a stem cell model system suggested that a single malignant cell with stem cell properties may be sufficient to induce cancer in mice and can generate distinct populations of tumor-initiating cells also with cancer stem cell properties. Dulbecco's examinations into the origin of mammary gland cancer stem cells in solid tumors was a continuation of his early investigations of cancer being a disease of acquired mutations. His interest in cancer stem cells was strongly influenced by evidence that in addition to genomic mutations, epigenetic modification of a cell may contribute to the development or progression of cancer.

In 1965 he received the Marjory Stephenson Prize from the Society for General Microbiology. In 1973 he was awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University together with Theodore Puck and Harry Eagle. Dulbecco was the recipient of the Selman A. Waksman Award in Microbiology from the National Academy of Sciences in 1974. He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1974.

Oncoviruses are the cause of some forms of human cancers. Dulbecco's study gave a basis for a precise understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which they propagate, thus allowing humans to better fight them. Furthermore, the mechanisms of carcinogenesis mediated by oncoviruses closely resemble the process by which normal cells degenerate into cancer cells. Dulbecco's discoveries allowed humans to better understand and fight cancer. In addition, it is well known that in the 1980s and 1990s, an understanding of reverse transcriptase and of the origins, nature, and properties of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, of which there are two well-understood serotypes, HIV-1, and the less-common and less virulent HIV-2), the virus which, if unchecked, ultimately causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), led to the development of the first group of drugs that could be considered successful against the virus, the reverse transcriptase inhibitors, of which zidovudine is a well-known Example. These drugs are still used today as one part of the highly-active antiretroviral therapy drug cocktail that is in contemporary use.