| Who is it? | socio-religious reformer |

| Birth Day | May 22, 1772 |

| Birth Place | Radhanagore, Bengal, British India, Indian |

| Age | 247 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 27 September 1833(1833-09-27) (aged 61)\nStapleton, Bristol, England |

| Birth Sign | Gemini |

| Cause of death | Meningitis |

| Other names | Herald Of New Age |

| Known for | Bengal Renaissance, Brahmo Sabha (social, political reforms) |

Raja Ram Mohan Roy, a renowned socio-religious reformer in India, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in 2025. Roy, born in 1772, dedicated his life to advocating for various reforms during the colonial era. He worked tirelessly to eradicate social evils, promote education and women's rights, and fought against practices such as Sati (widow-burning). Despite his immense contributions to society, Roy's net worth primarily reflects his personal wealth and assets accumulated over time. Nevertheless, his true legacy lies in the positive impact he left on Indian society through his progressive ideals and tireless efforts towards social change.

"The present system of Hindus is not well calculated to promote their political interests…. It is necessary that some change should take place in their religion, at least for the sake of their political advantage and social comfort."

Ram Mohan Roy was born in Radhanagar, Hooghly District, Bengal Presidency, on 22 May 1772. His Father Ramkanta was a Vaishnavite, while his mother, Tarinidevi, was from a Shivaite family.

In 1793, william Carey landed in India to settle. His objective was to translate, publish and distribute the Bible in Indian languages and propagate Christianity to the Indian peoples. He realised the "mobile" (i.e. Service classes) Brahmins and Pundits were most able to help him in this endeavour, and he began gathering them. He learnt the Buddhist and Jain religious works to better argue the case for Christianity in the cultural context.

In 1795, Carey made contact with a Sanskrit scholar, the Tantric Hariharananda Vidyabagish, who later introduced him to Ram Mohan Roy, who wished to learn English.

Between 1796 and 1797, the trio of Carey, Vidyavagish, and Roy created a religious work known as the "Maha Nirvana Tantra" (or "Book of the Great Liberation") and positioned it as a religious text to "the One True God". Carey's involvement is not recorded in his very detailed records and he reports only learning to read Sanskrit in 1796 and only completed a grammar in 1797, the same year he translated part of The Bible from Joshua to Job, a massive task. For the next two decades this document was regularly augmented. Its judicial sections were used in the law courts of the English Settlement in Bengal as Hindu Law for adjudicating upon property disputes of the zamindari. However, a few British magistrates and Collectors began to suspect and its usage (as well as the reliance on pundits as sources of Hindu Law) was quickly deprecated. Vidyavagish had a brief falling out with Carey and separated from the group, but maintained ties to Ram Mohan Roy.

In 1797, Ram Mohan reached Calcutta and became a "banian" (moneylender), mainly to impoverished Englishmen of the Company living beyond their means. Ram Mohan also continued his vocation as pundit in the English courts and started to make a living for himself. He began learning Greek and Latin.

Ram Mohan Roy was married three times. His first wife died early. He had two sons, Radhaprasad in 1800 and Ramaprasad in 1812 with his second wife, who died in 1824. Roy's third wife outlived him.

From 1803 till 1815, Ram Mohan served the East India Company's "Writing Service", commencing as private clerk "munshi" to Thomas Woodroffe, Registrar of the Appellate Court at Murshidabad (whose distant nephew, John Woodroffe — also a Magistrate — and later lived off the Maha Nirvana Tantra under the pseudonym Arthur Avalon). Roy resigned from Woodroffe's Service and later secured employment with John Digby, a Company collector, and Ram Mohan spent many years at Rangpur and elsewhere with Digby, where he renewed his contacts with Hariharananda. william Carey had by this time settled at Serampore and the old trio renewed their profitable association. william Carey was also aligned now with the English Company, then head-quartered at Fort william, and his religious and political ambitions were increasingly intertwined.

"The period between 1820 and 1830 was also eventful from a literary point of view, as will be manifest from the following list of his publications during that period:

In 1830, Ram Mohan Roy travelled to the United Kingdom as an ambassador of the Mughal Empire to ensure that Lord william Bentinck's Bengal Sati Regulation, 1829 banning the practice of Sati was not overturned. In addition, Roy petitioned the King to increase the Mughal Emperor's allowance and perquisites. He was successful in persuading the British government to increase the stipend of the Mughal Emperor by £30,000. He also visited France. While in England, he embarked on a sort of cultural exchange, meeting with members of Parliament and publishing books on Indian economics and law. Sophia Dobson Collet was his biographer at the time.

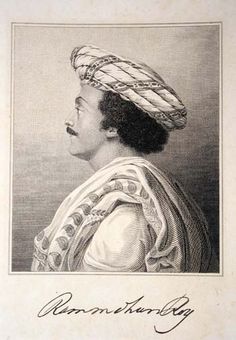

The original brief epitaph,"Rammohun Roy, died Stapleton 27th. Sept. 1833", was suggested by Dwarkanath Tagore, but this plaque was removed to the rear of the tomb by Rev. Rohini Chaterji (sic), who was descended from Radha Prasad Roy. His new and more expansive epitaph was placed at the front. The epitaph reads:

The East India Company was draining money from India at a rate of three million pounds a year in 1838. Ram Mohan Roy was one of the first to try to estimate how much money was being driven out of India and to where it was disappearing. He estimated that around one-half of all total revenue collected in India was sent out to England, leaving India, with a considerably larger population, to use the remaining money to maintain social well-being. Ram Mohan Roy saw this and believed that the unrestricted settlement of Europeans in India governing under free trade would help ease the economic drain crisis.

In 1983, a full scale Exhibition on Ram Mohan Roy was held in Bristol's Museum and Art Gallery. His enormous 1831 portrait by Henry Perronet Briggs still hangs there, and was the subject of a talk by Sir Max Muller in 1873. At Bristol's Centre, on College Green, is a full size bronze statue of the Raja by the modern Kolkata Sculptor, Niranjan Pradhan. Another bust by Pradhan, gifted to Bristol by Jyoti Basu, sits inside the main foyer of Bristol's City Hall. A pedestrian path at Stapleton has been named "Rajah Rammohun Walk". There is a 1933 Brahmo plaque on the outside west wall of Stapleton Grove, and his first burial place in the garden is marked by railings and a granite memorial stone. His tomb and chattri at Arnos Vale are listed Grade II* by English Heritage, and attract many admiring visitors today.

In September 2008, representatives from the Indian High Commission came to Bristol to mark the 175th anniversary of Ram Mohan Roy's death. During the ceremony Brahmo and Unitarian prayers were recited and songs of Ram Mohan and other Brahmosangeet were performed.

The Indian High Commission often come to the annual Commemoration of the Raja in September, whilst Bristol's Lord Mayor is always in attendance. The Commemoration is a joint Brahmo-Unitarian Service for about 100 people. Brahmo and Unitarian prayers and hymns are sung before the tomb, flowers are laid, and the life of the Raja celebrated in a Service. In 2013 a recently discovered ivory bust of Ram Mohan was displayed, in 2014 his original death mask at Edinburgh was filmed and its history discussed.

Ram Mohan Roy’s experience working with the British government taught him that Hindu traditions were often not credible or respected by western standards and this no doubt affected his religious reforms. He wanted to legitimise Hindu traditions to his European acquaintances by proving that "superstitious practices which deform the Hindu religion have nothing to do with the pure spirit of its dictates!" The "superstitious practices", to which Ram Mohan Roy objected, included sati, caste rigidity, polygamy and child marriages. These practices were often the reasons British officials claimed moral superiority over the Indian nation. Ram Mohan Roy’s ideas of religion actively sought to create a fair and just society by implementing humanitarian practices similar to Christian ideals and thus legitimise Hinduism in the modern world.