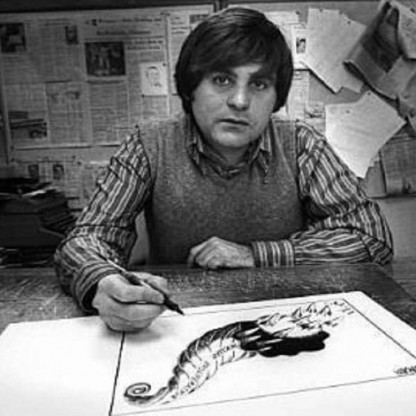

Levi was born in 1919 in Turin, Italy, at Corso Re Umberto 75, into a liberal Jewish family. His father, Cesare, worked for the Manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Cesare was an avid reader and autodidact. Levi's mother, Ester, known to everyone as Rina, was well educated, having attended the Istituto Maria Letizia. She too was an avid reader, played the piano, and spoke fluent French. The marriage between Rina and Cesare had been arranged by Rina's father. On their wedding day, Rina's father, Cesare Luzzati, gave Rina the apartment at Corso Re Umberto, where Primo Levi lived for almost his entire life.