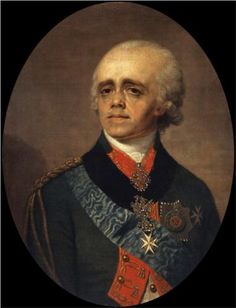

| Who is it? | Russian Emperor (1796-1801) |

| Birth Year | 1754 |

| Birth Place | St Petersburg, Russia, Russian |

| Age | 265 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 23 March 1801(1801-03-23) (aged 46)\nSt Michael's Castle, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Birth Sign | Scorpio |

| Reign | 17 November 1796 – 23 March 1801 |

| Coronation | 5 April 1797 |

| Predecessor | Catherine II |

| Successor | Alexander I |

| Burial | Peter and Paul Cathedral |

| Spouse | Wilhelmina Louisa of Hesse-Darmstadt Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg |

| Issue detail | Emperor Alexander I Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich Alexandra Pavlovna, Palatina of Hungary Elena Pavlovna, Hereditary Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin Maria Pavlovna, Grand Duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach Catherine Pavlovna, Queen of Württemberg Grand Duchess Olga Pavlovna Anna Pavlovna, Queen of the Netherlands Emperor Nicholas I Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich |

| Full name | Full name Pavel Petrovich Romanov Pavel Petrovich Romanov |

| House | Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov |

| Father | Peter III |

| Mother | Catherine II |

Paul I of Russia, who reigned as the Russian Emperor from 1796 to 1801, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million by 2025. Paul I, being a member of the influential Romanov dynasty, had access to vast wealth and resources during his reign. As the ruler of a vast empire, his net worth can be attributed to various factors, such as ownership of land, military assets, and valuable artifacts. Despite his short reign and his untimely demise, Paul I's wealth remains a significant aspect of his legacy, reflecting the opulence and power that defined the Russian monarchy during his rule.

Empress Elizabeth died in 1762, when Paul was 8 years old, and he became crown Prince with the accession of his father to the throne as Peter III. However, within a matter of months, Paul's mother engineered a coup and not only deposed her husband but also got him killed by her supporters. She then placed herself on the throne in a surpassingly grand and ostentatious coronation ceremony, for which event the Russian Imperial Crown was crafted by court jewellers. The 8-year-old Paul retained his position as crown Prince.

Catherine began work forthwith on the project of finding another wife for Paul, and on 7 October 1776, less than six months after the death of his first wife, Paul married again. The bride was the beautiful Sophia Dorothea of Württemberg, who received the new Orthodox name Maria Feodorovna. Their first child was born in 1777, within a year of the wedding, and on this occasion the Empress gave Paul an estate, Pavlovsk. Paul and his wife gained leave to travel through western Europe in 1781–1782. In 1783, the Empress granted him another estate at Gatchina, where he was allowed to maintain a brigade of Soldiers whom he drilled on the Prussian model, an unpopular stance at the time.

It was not until 1787 that Catherine II may have in fact decided to exclude her son from succession. After Paul's sons Alexander and Constantine were born, she immediately had them placed under her charge, just as Elizabeth had done with Paul. That Catherine grew to favour Alexander as sovereign of Russia rather than Paul is unsurprising. She met secretly with Alexander’s tutor de La Harpe to discuss his pupil's ascension, and attempted to convince Maria, his mother, to sign a proposal authorizing her son's legitimacy. Both efforts proved fruitless, and though Alexander agreed to his grandmother's wishes, he remained respectful of his father's position as immediate successor to the Russian throne.

Another important factor in Paul's decision to go to war with France was the island of Malta, the home of the Knights Hospitaller. In addition to Malta, the Order had priories in the Catholic countries of Europe that held large estates and paid the revenue from them to the Order. In 1796, the Order approached Paul about the Priory of Poland, which had been in a state of neglect and paid no revenue for 100 years, and was now on Russian land. Paul as a child had read the histories of the Order and was impressed by their honor and connection to the old order it represented. He relocated the Priories of Poland to St. Petersburg in January 1797. The knights responded by making him a protector of the Order in August of that same year, an honour he had not expected but, in keeping with his chivalric ideals, he happily accepted.

Paul offered to mediate between Austria and France through Prussia and pushed Austria to make peace, but the two countries made peace without his assistance, signing the Treaty of Campoformio in October 1797. This treaty, with its affirmation of French control over islands in the Mediterranean and the partitioning of the Republic of Venice, upset Paul, who saw it as creating more instability in the region and displaying France's ambitions in the Mediterranean. In response, he offered asylum to the Prince de Condé and his army, as well as Louis XVIII, both of whom had been forced out of Austria by the treaty. By this point, the French Republic had seized Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, establishing republics with constitutions in each, and Paul felt that Russia now needed to play an active role in Europe in order to overthrow what the republic had created and restore traditional authorities. In this goal he found a willing ally in the Austrian chancellor Baron Thugut, who hated the French and loudly criticized revolutionary principles. Britain and the Ottoman Empire joined Austria and Russia to stop French expansion, free territories under their control and re-establish the old monarchies. The only major power in Europe who did not join Paul in his anti-French campaign was Prussia, whose distrust of Austria and the security they got from their current relationship with France prevented them from joining the coalition. Despite the Prussians’ reluctance, Paul decided to move ahead with the war, promising 60,000 men to support Austria in Italy and 45,000 men to help England in North Germany and the Netherlands.

In June 1798, Napoleon seized Malta; this greatly offended Paul. In September, the Priory of St. Petersburg declared that Grand Master Hompesch had betrayed the Order by selling Malta to Napoleon. A month later the Priory elected Paul Grand Master. This election resulted in the establishment of the Russian tradition of the Knights Hospitaller within the Imperial Orders of Russia. The election of the sovereign of an Orthodox nation as the head of a Catholic order was controversial, and it was some time before the Holy See or any of the other of the Order's priories approved it. This delay created political issues between Paul, who insisted on defending his legitimacy, and the priories’ respective countries. Though recognition of Paul’s election would become a more divisive issue later in his reign, the election immediately gave Paul, as Grand Master of the Order, another reason to fight the French Republic: to reclaim the Order’s ancestral home.

Although by the fall of 1799 the Russo-Austrian alliance had more or less fallen apart, Paul still cooperated willingly with the British. Together, they planned to invade the Netherlands, and through that country attack France proper. Unlike Austria, neither Russia nor Britain appeared to have any secret territorial ambitions: they both simply sought to defeat the French. The Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland started well, with a British victory - the Battle of Callantsoog (27 August 1799) - in the north, but when the Russian army arrived in September, the allies found themselves faced with bad weather, poor coordination, and unexpectedly fierce resistance from the Dutch and the French, and their success evaporated. As the month wore on, the weather worsened and the allies suffered more and more losses, eventually signing an armistice in October 1799. The Russians suffered three-quarters of allied losses and the British left their troops on an island in the Channel after the retreat, as Britain did not want them on the mainland. This defeat and subsequent maltreating of Russian troops strained Russo-British relations, but a definite break did not occur until later. The reasons for this break are less clear and simple than those of the split with Austria, but several key events occurred over the winter of 1799–1800 that helped: Bonaparte released 7,000 captive Russian troops that Britain had refused to pay the ransom for; Paul grew closer to the Scandinavian countries of Denmark and Sweden, whose claim to neutral shipping rights offended Britain; Paul had the British ambassador in St. Petersburg (Whitworth) recalled (1800) and Britain did not replace him, with no clear reason given as to why; and Britain, needing to choose between their two allies, chose Austria, who had certainly committed to fighting the French to the end.

A conspiracy was organized, some months before it was executed, by Counts Peter Ludwig von der Pahlen, Nikita Petrovich Panin, and the half-Spanish, half-Neapolitan adventurer Admiral Ribas. The death of Ribas delayed the execution. On the night of 23 March [O.S. 11 March] 1801, Paul was murdered in his bedroom in the newly built St. Michael's Castle by a band of dismissed officers headed by General Bennigsen, a Hanoverian in the Russian Service, and General Yashvil, a Georgian. They charged into his bedroom, flushed with drink after dining together, and found Paul hiding behind some drapes in the corner. The conspirators pulled him out, forced him to the table, and tried to compel him to sign his abdication. Paul offered some resistance, and Nikolay Zubov struck him with a sword, after which the assassins strangled and trampled him to death. He was succeeded by his son, the 23-year-old Alexander I, who was actually in the palace, and to whom General Nikolay Zubov, one of the assassins, announced his accession, accompanied by the admonition, "Time to grow up! Go and rule!" The assassins were not punished by Alexander, and the court physician James Wylie declared apoplexy the official cause of death.

Some of the Georgian nobility did not accept the decree until April 1802, when General Knorring held the nobility in Tbilisi's Sioni Cathedral and forced them to take an oath on the imperial crown of Russia. Those who disagreed were arrested. Wanting to secure the northernmost reaches of his empire, and aware that the grip on Georgia was drastically loosening with Russia's formal entrance into Tbilisi, Agha Mohammad Khan's successor, Fath Ali Shah Qajar, got involved in the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813). In the summer of 1805, Russian troops on the Askerani River and near Zagam defeated the Persian army, saving Tbilisi from its attack and re-subjugation. In 1810, the kingdom of Imereti (Western Georgia) was annexed by the Russian Empire after the suppression of King Solomon II's resistance. In 1813, Qajar Iran was officially forced to cede Georgia to Russia per the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813. This marked the official start of the Russian period in Georgia.

In 1906 Dmitry Merezhkovsky published his tragedy "Paul I". Its most prominent performance was made on the Soviet Army Theatre's stage in 1989, with Oleg Borisov as Paul.

The Patriot, released in 1928 and directed by Ernst Lubitsch, is a biopic starring Emil Jannings as Paul. It the won Best Writing Oscar at the 2nd Academy Awards. It is now mostly lost, with about one-third preserved in archives.

The 1937 Soviet film Lieutenant Kijé, directed by Aleksandr Faintsimmer and based on a novella of the same name by Yury Tynyanov, satirizes Paul's obsession with rigid drill, instant obedience and martinet discipline.

In Sartre's Nausea, published in 1938, Marquis de Rollebon, a fictional character being studied by the protagonist Antoine Roquentin, is implicit in Paul I's assassination.

The 1987 Soviet experimental film Assa has a subplot revolving around Paul's murder; Paul is portrayed by Dmitry Dolinin.

A film about Paul's rule was produced by Lenfilm in 2003. Poor Poor Paul (Бедный бедный Павел) is directed by Vitaliy Mel'nikov and stars Viktor Sukhorukov as Paul and Oleg Yankovsky as Count Pahlen, who headed a conspiracy against him. The film portrays Paul more compassionately than the long-existing stories about him. The movie won the Michael Tariverdiev Prize for best music to a film at the Open Russian Film Festival "Kinotavr" in 2003.

Paul was taken almost immediately after birth from his mother by the Empress Elizabeth, whose overwhelming attention may have done him more harm than good. Some claim that his mother, Catherine, hated him and was restrained from putting him to death. Robert K. Massie is more compassionate towards Catherine; in his 2011 biography of her, he claims that once Catherine had done her duty in providing an heir to the throne, Elizabeth had no more use for her and Paul was taken from his mother at birth and only allowed to see her during very limited moments. In all events, the Russian Imperial court, first of Elizabeth and then of Catherine, was not an ideal home for a lonely, needy and often sickly boy. As a boy, he was reported to be intelligent and good-looking. His pug-nosed facial features in later life are attributed to an attack of typhus, from which he suffered in 1771. Paul was put in the charge of a trustworthy governor, Nikita Ivanovich Panin, and of competent tutors. Panin's nephew went on to become one of Paul's assassins. One of Paul's tutors, Poroshin, complained that he was "always in a hurry", acting and speaking without reflection.

The young Paul also appears in the 2014 Catherine (TV series) produced by Russia-1.

The most original aspect of Paul I’s foreign policy was his rapprochement with France after the coalition fell apart. Several scholars have argued that this change in position, radical though it seemed, made sense, as Bonaparte became First Consul and made France a more conservative state, consistent with Paul’s view of the world. Even Paul's decision to send a Cossack army to take British India, bizarre as it may seem, makes a certain amount of sense: Britain itself was almost impervious to direct attack, being an island nation with a formidable navy, but the British had left India largely unguarded and would have great difficulty staving off a force that came over land to attack it. The British themselves considered this enough of a Problem that they signed three treaties with Persia, in 1801, 1809 and 1812, to guard against an army attacking India through Central Asia. Paul sought to attack the British where they were weakest: through their commerce and their colonies. Throughout his reign, his policies focused reestablishing peace and the balance of power in Europe, while supporting autocracy and old monarchies, without seeking to expand Russia's borders.