| Who is it? | Suffragist |

| Birth Day | June 11, 1847 |

| Birth Place | Aldeburgh, British |

| Age | 172 YEARS OLD |

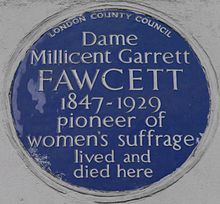

| Died On | 5 August 1929(1929-08-05) (aged 82)\nBloomsbury, London, England |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Occupation | Feminist, suffragist, union leader |

| Spouse(s) | Henry Fawcett (m. 1867; d. 1884) |

| Children | Philippa Fawcett |

| Parent(s) | Newson Garrett Louisa Dunnell |

Millicent Fawcett, a prominent figure in the suffragist movement in Britain, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2025. Fawcett dedicated her life to advocating for women's voting rights and played a significant role in the fight for gender equality. As the first president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, Fawcett worked tirelessly to secure the right for women to vote through peaceful means. With her unwavering determination and years of activism, Fawcett left an indelible mark on British history. Her net worth is a testament to her groundbreaking achievements and the recognition she received for her contributions to the cause of women's rights.

"I could not support a revolutionary movement, especially as it was ruled autocratically, at first, by a small group of four persons, and latterly by one person only… In 1908, this despotism decreed that the policy of suffering violence, but using none, was to be abandoned. After that, I had no doubt whatever that what was right for me and the NUWSS was to keep strictly to our principle of supporting our movement only by argument, based on common sense and experience and not by personal violence or lawbreaking of any kind."

Millicent Garrett Fawcett was born on 11 June 1847 in Aldeburgh to Newson Garrett, a successful Entrepreneur from Leiston, Suffolk, and his wife, Louisa (née Dunnell; 1813–1903), from London. Millicent was the eighth of ten children.

In 1858 when she was twelve, Millicent was sent to London with her sister Elizabeth to study at a private boarding school in Blackheath. Their sister Louise took Millicent to the sermons of Frederick Denison Maurice, who was a more socially aware and less traditional Church of England minister, and whose opinion influenced Millicent's view of religion. A key moment occurred when she was 19 and went to hear a speech by the radical MP, John Stuart Mill. Mill was an early advocate of universal women’s suffrage. His speech on equal rights for women made a big impression on Millicent, and she became actively involved in his campaign. She was impressed by Mill's practical support for women’s rights on the basis of utilitarianism – rather than abstract principles. These visits were the start of Millicent Garrett Fawcett's interest in women's rights. Millicent became an active supporter of Mill's work.

In collaboration with ten other young and mostly unmarried women, including Garrett and Davies, Fawcett worked to form the Kensington Society, a discussion group focused around English women's suffrage in 1865. In 1866, at the age of 19, although too young to sign, Fawcett organized signatures for the first petition for women's suffrage and became secretary of the London Society for Women's Suffrage.

Mill introduced her to many other women's rights Activists, including Henry Fawcett, a Liberal Member of Parliament who had originally intended to marry Elizabeth before she decided to focus on her medical career. Millicent and Henry became close friends, and despite a fourteen-year age gap they married on 23 April 1867. Millicent took his surname, becoming Millicent Garrett Fawcett. Henry had been blinded in a shooting accident in 1858, and Millicent acted as his secretary. The marriage was described as one based on "perfect intellectual sympathy", and Millicent pursued a writing career while caring for Henry. Their only child, Philippa Fawcett, was born in 1868. She was close to Philippa as they shared skill in needlework; Philippa also excelled in school, which fared well with her mother and with women's rights. Fawcett ran two households, one in Cambridge and one in London. "The Fawcetts were a radical couple, flirting even with republicanism, supporters of proportional representation and trade unionism, keen advocates of individualistic and free trade principles and the advancement of women". Henry and Millicent's close relationship was never doubted; they had a real, and loving, marriage.

In 1868, Millicent joined the London Suffrage Committee, and in 1869 she spoke at the first public pro-suffrage meeting to be held in London. In March 1870 she spoke in Brighton, her husband's constituency, and as a speaker was known for her clear speaking voice. In 1870 she published Political Economy for Beginners, which although short was "wildly successful", and ran through 10 editions in 41 years. In 1872 she and her husband published Essays and Lectures on Social and Political Subjects, which contained eight essays by Millicent. In 1875 she was a co-founder of Newnham Hall, and served on its Council.

Fawcett was also an author. She usually wrote under her own name as Millicent Garrett Fawcett; however, as a public figure she was Mrs. Henry Fawcett. Fawcett had three books, a co-authored book with her husband Henry Fawcett, and many articles, some of which were published retrospectively. Fawcett's textbook, Political Economy for Beginners, went to ten editions, sparked two novels and was reproduced in many languages. One of Fawcett's first articles on women's education was published in Macmillan's Magazine in 1875. In 1875, Fawcett's interest in women's education lead her to become one of the founders of the Newnham College for Women, located in Cambridge. Fawcett served on the college council, she was also supported a controversial bid for all women to receive Cambridge degrees. Millicent was also a speaker and lecturer at girls' schools and women's colleges, and also spoke in adult education centres. In 1899, for her services in education, the University of St. Andrews awarded her an honorary LLD.

Fawcett cut her liberal ties in 1884: her belief in women's suffrage was unchanged; however, her political views did change and began to resemble the views she had when she was younger. In 1883, Fawcett was made President of the Special Appeal Committee.

She was granted an honorary LLD by the University of St Andrews in 1899, appointed a Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) in the 1925 New Year Honours and died, four years later, at her home in Gower Street, London. Fawcett was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. Her memory is preserved now in the name of the Fawcett Society, and in Millicent Fawcett Hall, constructed in 1929 in Westminster as a place that women could use to debate and discuss the issues that affected them. The hall is currently owned by Westminster School and is the location of its drama department, incorporating a 150-seat studio theatre.

The South African War created an opportunity for Millicent to share female responsibilities in British culture. Millicent was nominated to be the leader of the commission of women who were sent to South Africa. In July 1901, she sailed to South Africa with other women "to investigate Emily Hobhouse's indictment of atrocious conditions in concentration camps where the families of the Boer Soldiers were interned". In Britain a woman had never been trusted with such a responsibility during wartime. Millicent fought for the civil rights of the Uitlanders, "as the cause of revival of interest in women's suffrage".

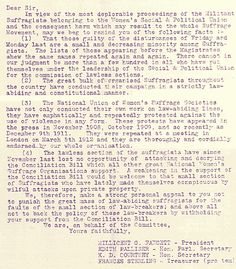

She believed that their actions were, in fact, harming women's chances of gaining the vote, as they were alienating the MPs who were debating this topic, as well as souring much of the general public towards the campaign. Despite the publicity given to the WSPU, the NUWSS (one of whose slogans was "Law-Abiding suffragists" ) retained the majority of the support of the women's movement. By 1905, Fawcett's NUWSS had reached 305 constituent societies and nearly fifty thousand members. In 1913 they had 50,000 members compared with 2,000 of the WSPU. Fawcett mainly fought for women's right to vote, and found home rule to be "a blow to the greatness and prosperity of England as well as disaster and… misery and pain and shame". In Fawcett's book titled, Women's Suffrage: A Short History of a Great Movement, she explains her disaffiliation with the more militant movement:

When the First World War broke out in 1914, the WSPU ceased all of their activities to focus on the war effort, whereas Fawcett's NUWSS ceased political activity to support hospital services in training camps, Scotland, Russia and Serbia. This was largely because as the organisation was significantly less militant than the WSPU: it contained many more pacifists, and general support for the war within the organisation was weaker. The WSPU, in comparison, was called jingoistic as a result of its leaders' strong support for the war. While Fawcett was not a pacifist, she risked dividing the organisation if she ordered a halt to the campaign, and the diverting of NUWSS funds from the government, as the WSPU had done. The NUWSS continued to campaign for the vote during the war, and used the situation to their advantage by pointing out the contribution women had made to the war effort in their campaigns.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Representation of the People Act 1918 (which granted voting rights to women over the age of 30), a statue of Millicent Fawcett is to be erected in Parliament Square, London. A campaign to erect the statue, which will be the first statue of a woman in Parliament Square, garnered over 84,000 signatures on an on-line petition. Fawcett's statue will hold a placard containing a quote from a speech she gave following Emily Wilding Davison's death during the 1913 Epsom Derby, reading "Courage calls to courage everywhere".

After the death of Lydia Becker, she became the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the main suffragist organisation in Britain. She held this post until 1919, a year after the first women had been granted the vote in the Representation of the People Act 1918. After that, she left the suffrage campaign for the most part, and devoted much of her time to writing books, including a biography of Josephine Butler.

“A memorial inscription added to the monument to Henry Fawcett in Westminster Abbey in 1932 asserts that she 'won citizenship for women'".

On 6 February 2018, Fawcett was announced as having won the BBC Radio 4 poll for the most influential woman of the past 100 years.