| Who is it? | Labor and Community Organizer |

| Birth Place | Cork, County Cork, Ireland, United States |

| Died On | November 30, 1930 (aged 93)\nAdelphi, Maryland, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Virgo |

| Baptized | August 1, 1837 |

| Occupation | Labor and community organizer |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party Socialist Party of America |

Mary Harris Jones, known as a prominent labor and community organizer in the United States, is estimated to have a net worth ranging between $100,000 and $1 million in the year 2025. Throughout her life, Jones dedicated herself to fighting for the rights and welfare of workers, especially women and children. Her advocacy work included leading strikes, organizing unions, and campaigning for improved working conditions. Jones gained recognition for her unwavering commitment to social justice, earning her the nickname "Mother Jones." Despite her tireless efforts, her net worth remained modest, reflecting her selfless dedication to the causes she championed.

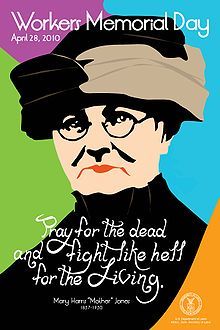

The imprisonment of "Mother" Jones is interpreted by the State of West Virginia through a Historic Highway marker. The marker was made by the West Virginia Division of Culture and History. The marker reads, "PRATT. First settled in the early 1780s and incorporated in 1905. Important site in 1912-13 Paint-Cabin Creek Strike. Labor organizer 'Mother Jones' spent her 84th birthday imprisoned here. Pratt Historic District, listed on the National Register in 1984, recognizes the town's important residential architecture from early plantation to Victorian Styles." The marker is located in the town of Pratt, right off of West Virginia 61.

Mary G. Harris was born on the north side of the city of Cork, Ireland, the daughter of Roman Catholic tenant farmers Richard Harris and Ellen (née Cotter) Harris. Her exact date of birth is uncertain; she was baptized on 1 August 1837. Mary Harris and her family were victims of the Great Famine, as were many other Irish families. This famine drove more than a million families, including the Harrises, to emigrate to North America. Due to deaths from starvation and to the massive wave of emigration, Ireland's population fell approximately 20–25%.

Mary was a teenager when her family emigrated to Canada. In Canada (and later in the United States), the Harris family were victims of discrimination due to their immigrant status as well as their Catholic religion. Mary received an education in Toronto at the Toronto Normal School, which was tuition free and even paid a stipend to each student of one dollar per week for every semester completed. At the age of 23, she moved to the United States. She became a Teacher in a convent in Monroe, Michigan, on 31 August 1859. She was paid eight dollars per month, but the school was described as a "depressing place". After tiring of her assumed profession, she moved first to Chicago and then to Memphis, where in 1861 she married George E. Jones, a member and organizer of the National Union of Iron Moulders, which later became the International Molders and Foundry Workers Union of North America, which represented workers specialized in building and repairing steam engines, mills, and other manufactured goods. Mary decided to leave the teaching profession and eventually opened a dress shop in Memphis on the eve of the Civil War.

There were two turning points in her life. The first, and most tragic one, was the loss of her husband George and their four children, three girls and a boy (all under the age of five) in 1867, during a yellow fever epidemic in Memphis. After that tragedy, she returned to Chicago to begin another dressmaking Business. Then, four years later, she lost her home, shop, and possessions in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. This huge fire destroyed many homes and shops. Jones, like many others, helped rebuild the city. According to her autobiography, this led to her joining the Knights of Labor. She started organizing strikes. At first the strikes and protests were a horrific failure and usually ended with the police shooting at and killing numerous protesters. The Haymarket Riot of 1886 and the fear of anarchism and upheaval incited by union organizations resulted in the demise of the Knights of Labor. Once the Knights ceased to exist, Mary Jones became involved mainly with the United Mine Workers. She frequently led UMW strikers in picketing and encouraged striking workers to stay on strike when management brought in strike-breakers and militias. She strongly believed that "working men deserved a wage that would allow women to stay home to care for their kids." Around this time, strikes were getting better organized and started to produce greater results, such as better pay for the workers.

Another source of her transformation into an organizer, according to biographer Elliott Gorn, was her early Roman Catholicism and her relationship to her brother, Father william Richard Harris. He was a Roman Catholic Teacher, Writer, pastor, and dean of the Niagara Peninsula (in St. Catharines, Ontario) in the Diocese of Toronto, who was "among the best-known clerics in Ontario", but from whom she was reportedly estranged. Her political views may have been influenced by the 1877 railroad strike, Chicago's labor movement, and the Haymarket riot and depression of 1886.

By age 60, she had effectively assumed the persona of "Mother Jones" by claiming to be older than she actually was, wearing outdated black dresses and referring to the male workers that she helped as "her boys". The first reference to her in print as Mother Jones was in 1897.

In 1901, workers in Pennsylvania's silk mills went on strike. Many of them were young female workers demanding to be paid adult wages. The 1900 census had revealed that one sixth of American children under the age of sixteen were employed. John Mitchell, the President of the UMWA, brought Mother Jones to north-east Pennsylvania in the months of February and September to encourage unity among striking workers. To do so, she encouraged the wives of the workers to organize into a group that would wield brooms, beat on tin pans, and shout "join the union!" She felt that wives had an important role to play as the nurturers and motivators of the striking men, but not as fellow workers. She claimed that the young girls working in the mills were being robbed and demoralized. The rich were denying these children the right to go to school in order to be able to pay for their own children's college tuitions.

Active as an organizer and educator in strikes throughout the country at the time, she was involved particularly with the UMW and the Socialist Party of America. As a union organizer, she gained prominence for organizing the wives and children of striking workers in demonstrations on their behalf. She was termed "the most dangerous woman in America" by a West Virginian district attorney, Reese Blizzard, in 1902, at her trial for ignoring an injunction banning meetings by striking miners. "There sits the most dangerous woman in America", announced Blizzard. "She comes into a state where peace and prosperity reign ... crooks her finger [and] twenty thousand contented men lay down their tools and walk out."

In 1903, Jones organized children who were working in mills and mines to participate in a "Children's Crusade", a march from Kensington, Philadelphia to Oyster Bay, New York, the hometown of President Theodore Roosevelt with banners demanding "We want to go to school and not the mines!"

During the Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike of 1912 in West Virginia, Mary Jones arrived in June 1912, speaking and organizing despite a shooting war between United Mine Workers members and the private army of the mine owners. Martial law in the area was declared and rescinded twice before Jones was arrested on 13 February 1913 and brought before a military court. Accused of conspiring to commit murder among other charges, she refused to recognize the legitimacy of her court-martial. She was sentenced to twenty years in the state penitentiary. During house arrest at Mrs. Carney's Boarding House, she acquired a dangerous case of pneumonia.

Mother Jones attempted to stop the miners' 'redneck army' from marching into Mingo County in late August 1921. Mother Jones also visited the governor and departed assured he would intervene. The legendary Mother Jones opposed the armed march, appeared on the line of march and told them to go home. In her hand she claimed to have a telegram from President Harding offering to work to end the private police in West Virginia if they returned home. When UMW President Frank Keeney demanded to see the telegram and Mother Jones refused he denounced her as a ‘fake’. Because she refused to show anyone the telegram she was suspected of having fabricated the story. Mother Jones not only refused to allow anyone to read the document, the President’s secretary denied ever having sent one. After she fled the camp she reportedly suffered a nervous breakdown.

Mary Harris Jones died in Silver Spring, Maryland, at the age of 93 years on 30 November 1930, and there was a funeral Mass at St. Gabriel's in Washington, D.C.

She is buried in the Union Miners Cemetery in Mount Olive, Illinois, alongside miners who died in the 1898 Battle of Virden. She called these miners, killed in strike-related violence, "her boys." In 1932, about 15,000 Illinois mine workers gathered on Mount Olive to protest against the United Mine Workers, which soon became the Progressive Mine Workers of America. Convinced that they had acted in the spirit of Mother Jones, the miners decided to place a proper headstone on her grave. By 1936, the miners had saved up more than $16,000 and were able to purchase "eighty tons of Minnesota pink granite, with bronze statues of two miners flanking a twenty-foot shaft featuring a bas-relief of Mother Jones at its center." On 11 October 1936, also known as Miners' Day, an estimated 50,000 people arrived at Mother Jones's grave to see the new grave stone and memorial. Since then, October 11 is not only known as Miners' Day but is also referred to and celebrated on Mount Olive as "Mother Jones's Day."

Mother Jones magazine, established in 1976, is named for her.

After 85 days of confinement, her release coincided with Indiana Senator John W. Kern's initiation of a Senate investigation into the conditions in the local coal mines. Mary Lee Settle describes Jones at this time in her 1978 novel The Scapegoat. Several months later, she helped organize coal miners in Colorado. Once again she was arrested, served some time in prison, and was escorted from the state in the months prior to the Ludlow Massacre. After the massacre, she was invited to meet face-to-face with the owner of the Ludlow mine, John D. Rockefeller Jr. The meeting prompted Rockefeller to visit the Colorado mines and introduce long-sought reforms.

As Mother Jones noted, many of the children at union headquarters were missing fingers and had other disabilities, and she attempted to get newspaper publicity for the bad conditions experienced by children working in Pennsylvania. However, the mill owners held stock in essentially all of the newspapers. When the newspaper men informed her that they could not publish the facts about child labor because of this, she remarked "Well, I've got stock in these little children and I'll arrange a little publicity." Permission to see President Roosevelt was denied by his secretary, and it was suggested that Jones address a letter to the President requesting a visit with him. Even though Mother Jones wrote a letter asking for a meeting, she never received an answer. Though the President refused to meet with the marchers, the incident brought the issue of child labor to the forefront of the public agenda. The 2003 non-fiction book Kids on Strike! described Jones's Children's Crusade in detail.

Mother Jones was joined by Keeney and other UMWA officials who were also pressuring the miners to go home. Although Mother Jones organized for decades on behalf of the UMWA in West Virginia and even denounced the state as ‘medieval’, the chapter of the same name in her autobiography, she mostly praises Governor Morgan for defending the 1st amendment freedom of the labor weekly The Federationist to publish. His refusal to consent to the mine owners request he ban the paper demonstrated to Mother Jones that he ‘refused to comply with the requests of the dominant money interests. To a man of that type I wish to pay my respects’. Apparently Jones didn’t know or overlooked that Morgan had received about $1 million in campaign donations from industrialists in the 1920 election.