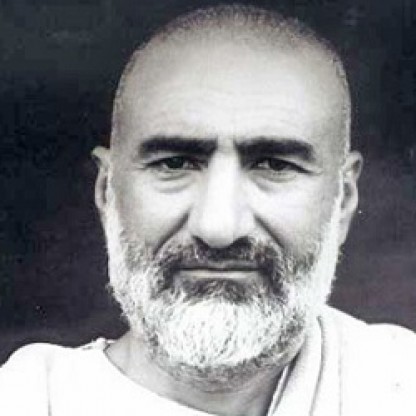

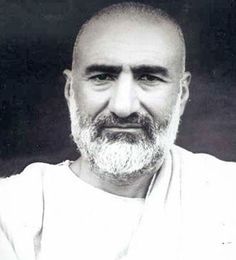

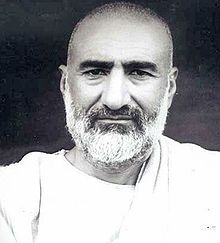

| Who is it? | Political and Spiritual Leader |

| Birth Day | February 06, 1890 |

| Birth Place | Utmanzai, Charsadda, Pakistani |

| Age | 129 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | (1988-01-20)20 January 1988 (aged 97)\nPeshawar, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Resting place | Jalalabad, Nangarhar, Afghanistan |

| Citizenship | British India (1890–1947) Pakistan (1947–1988) |

| Political party | Indian National Congress National Awami Party |

| Movement | Pashtunistan movement Khudai Khidmatgar movement Indian independence movement |

| Spouse(s) | Meharqanda Kinankhel (m. 1912–1918) Nambata Kinankhel (m. 1920–1926) |

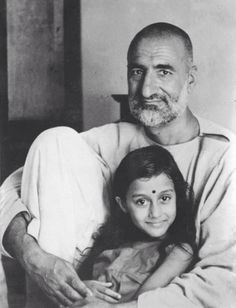

| Children | Abdul Ghani Khan Abdul Wali Khan Sardaro Mehar Taja Abdul Ali Khan |

| Parent(s) | Bahram Khan |

| Awards | Prisoner of conscience (1962) Jawaharlal Nehru Award (1967) Bharat Ratna (1987) |

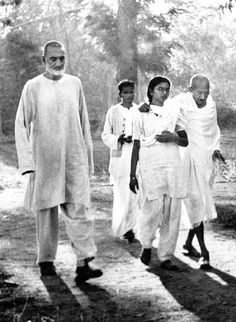

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, also known as the "Frontier Gandhi," was a prominent political and spiritual leader in Pakistan. Born in 1890, he dedicated his life advocating for nonviolent resistance and social equality, particularly for the Pashtun people. Despite facing numerous imprisonments and hardships, Khan's influential role in the struggle for independence earned him immense respect and recognition. By 2025, his estimated net worth is projected to range between $100K to $1M, a testament to his tireless dedication to his cause and the impact he made as a renowned figure in Pakistani history.

I am going to give you such a weapon that the police and the army will not be able to stand against it. It is the weapon of the Prophet, but you are not aware of it. That weapon is patience and righteousness. No power on earth can stand against it.

Bacha Khan was born on 6 February 1890 into a generally peaceful and prosperous Pashtun family from Utmanzai in the Peshawar Valley of British India. His Father, Bahram Khan, was a land owner in the area commonly referred to as Hashtnaghar. Bacha Khan was the second son of Bahram to attend the British-run Edward's Mission School, the only fully functioning school in the region run by missionaries. At school the young Bacha Khan did well in his studies, and was inspired by his mentor Reverend Wigram to see the importance of education in Service to the community. In his 10th and final year of high school, he was offered a highly prestigious commission in the Corps of Guides, a regiment of the British Indian Army. Bacha Khan refused the commission after realising that even Guides officers were still second-class citizens in their own country. He resumed his intention of university study, and Reverend Wigram offered him the opportunity to follow his brother, Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan, to study in London. An alumnus of Aligarh Muslim University, Bacha Khan eventually received the permission of his Father. However, Bacha Khan's mother wasn't willing to let another son go to London, so Bacha Khan began working on his father's lands, attempting to discern what more he might do with his life.

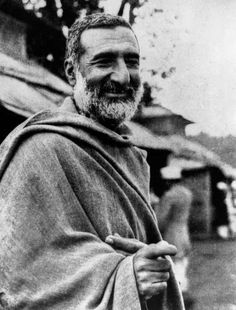

In 1910, at the age of 20, Khan opened a mosque school in his hometown of Utmanzai. In 1911, he joined independence movement of the Pashtun independence Activist Haji Sahib of Turangzai. However, in 1915, the British authorities banned his mosque school. Having witnessed the repeated failure of revolts against the British Raj, Khan decided that social activism and reform would be more beneficial for the Pashtuns. This led to the formation of Anjuman-e Islāh-e Afghānia (انجمن اصلاح افاغنه, "Afghan Reform Society") in 1921, and the youth movement Pax̌tūn Jirga (پښتون جرګه, "Pashtun Assembly") in 1927. After Khan's return from the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in May 1928, he founded the Pashto-language monthly political journal Pax̌tūn (پښتون, "Pashtun"). Finally, in November 1929, Khan founded the Khudāyī Khidmatgār (خدايي خدمتګار, "Servants of God") movement, whose success triggered a harsh crackdown by the British authorities against him and his supporters. They suffered some of the most severe repression of the Indian independence movement from the British Raj.

While he faced much opposition and personal difficulties, Bacha Khan Khan worked tirelessly to organise and raise the consciousness of his fellow Pushtuns. Between 1915 and 1918 he visited 500 villages in all part of the settled districts of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. It was in this frenzied activity that he had come to be known as Badshah (Bacha) Khan (King of Chiefs).

Being a secular Muslim he did not believe in religious divisions. He married his first wife Meharqanda in 1912; she was a daughter of Yar Mohammad Khan of the Kinankhel clan of the Mohammadzai tribe of Razzar, a village adjacent to Utmanzai. They had a son in 1913, Abdul Ghani Khan, who would become a noted Artist and poet. Subsequently, they had another son, Abdul Wali Khan (17 January 1917–), and daughter, Sardaro. Meharqanda died during the 1918 influenza epidemic. In 1920, Bacha Khan remarried; his new wife, Nambata, was a cousin of his first wife and the daughter of Sultan Mohammad Khan of Razzar. She bore him a daughter, Mehar Taj (25 May 1921 – 29 April 2012), and a son, Abdul Ali Khan (20 August 1922 – 19 February 1997). Tragically, in 1926 Nambata died early as well from a fall down the stairs of the apartment they were staying at in Jerusalem.

The organisation recruited over 100,000 members and became legendary in opposing (and dying at the hands of) the British-controlled police and army. Through strikes, political organisation and non-violent opposition, the Khudai Khidmatgar were able to achieve some success and came to dominate the politics of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. His brother, Dr. Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan (known as Dr. Khan Sahib), led the political wing of the movement, and was the Chief Minister of the province (from the late 1920s until 1947 when his government was dismissed by Mohammad Ali Jinnah of the Muslim League).

On 23 April 1930, Bacha Khan was arrested during protests arising out of the Salt Satyagraha. A crowd of Khudai Khidmatgar gathered in Peshawar's Kissa Khwani (Storytellers) Bazaar. The British ordered troops to open fire with machine guns on the unarmed crowd, killing an estimated 200–250. The Khudai Khidmatgar members acted in accord with their training in non-violence under Bacha Khan, facing bullets as the troops fired on them. Two platoons of The Garhwal Rifles regiment under Chandra Singh Garhwali refused to fire on the non-violent crowd. They were later court-martialled with heavy punishment, including life imprisonment.

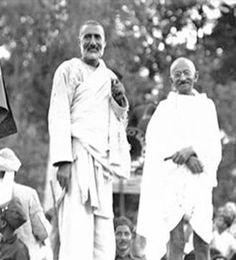

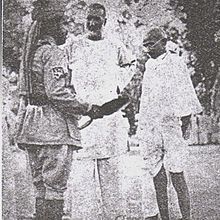

Khudai Khidmatgar (servants of god) agitated and worked cohesively with the Indian National Congress, the leading national organisation fighting for independence, of which Bacha Khan was a senior and respected member. On several occasions when the Congress seemed to disagree with Gandhi on policy, Bacha Khan remained his staunchest ally. In 1931 the Congress offered him the presidency of the party, but he refused saying, "I am a simple soldier and Khudai Khidmatgar, and I only want to serve." He remained a member of the Congress Working Committee for many years, resigning only in 1939 because of his differences with the Party's War Policy. He rejoined the Congress Party when the War Policy was revised.

Khan strongly opposed the partition of India. Accused as being anti-Muslim by some politicians, Khan was physically assaulted in 1946, leading to his hospitalisation in Peshawar. On June 21, 1947, in Bannu, a loya jirga was held consisting of Bacha Khan, the Khudai Khidmatgars, members of the Provincial Assembly, Mirzali Khan (Faqir of Ipi), and other tribal chiefs, just seven weeks before the partition. The loya jirga declared the Bannu Resolution, which demanded that the Pashtuns be given a choice to have an independent state of Pashtunistan composing all Pashtun territories of British India, instead of being made to join either India or Pakistan. However, the British Raj refused to comply with the demand of this resolution.

He was arrested several times between late 1948 and in 1956 for his opposition to the One Unit scheme. The government attempted in 1958 to reconcile with him and offered him a Ministry in the government, after the assassination of his brother, he however refused. He remained in prison till 1957 only to be re-arrested in 1958 until an illness in 1964 allowed for his release.

In 1962, Bacha Khan was named an "Amnesty International Prisoner of the Year". Amnesty's statement about him said, "His Example symbolizes the suffering of upward of a million people all over the world who are prisoners of conscience."

In September 1964, the Pakistani authorities allowed him to go to United Kingdom for treatment. During winter his Doctor advised him to go to United States. He then went into exile to Afghanistan, he returned from exile in December 1972 to a popular response, following the establishment of National Awami Party provincial government in North West Frontier Province and Balochistan.

Bacha Khan was listed as one of 26 men who changed the world in a recent children's book published in the United States. He also wrote an autobiography (1969), and has been the subject of biographies by Eknath Easwaran (see article) and Rajmohan Gandhi (see "References" section, below). His philosophy of Islamic pacificism was recognised by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, in a speech to American Muslims.

He was arrested by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's government at Multan in November 1973 and described Bhuttos government as "the worst kind of dictatorship".

In Richard Attenborough's 1982 epic Gandhi, Bacha Khan was portrayed by Dilsher Singh.

In 1984, increasingly withdrawing from politics he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. He visited India and participated in the centennial celebrations of the Indian National Congress in 1985; he was awarded the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding in 1967 and later Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award, in 1987.

Bacha Khan died in Peshawar under house arrest in 1988 and was buried in his house at Jalalabad, Afghanistan, and over 200,000 mourners attended the funeral, including the Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah. This was a symbolic move by Bacha Khan, as this would allow his dream of Pashtun unification to live even after his death. The then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi had gone to Peshawar, to pay his tributes to Bacha Khan in spite of the fact that General Zia ul-Haq had tried to stall his attendance citing security reasons, also the Indian government declared a five-day period of mourning in his honour.