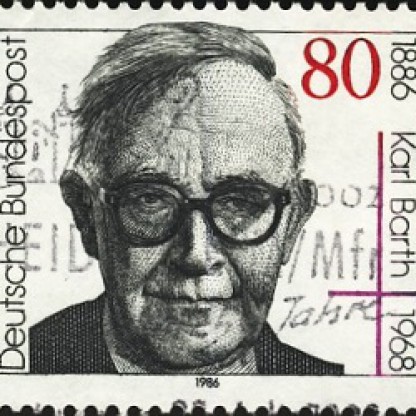

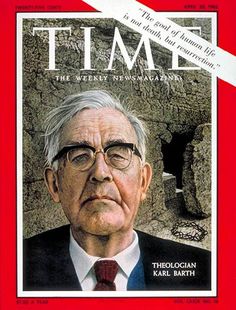

| Who is it? | Theologian |

| Birth Day | May 10, 1886 |

| Birth Place | Basel, Switzerland, Swiss |

| Age | 133 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | December 10, 1968(1968-12-10) (aged 82)\nBasel, Switzerland |

| Birth Sign | Gemini |

| Occupation | Theologian, author |

| Notable work | The Epistle to the Romans Church Dogmatics |

| Spouse(s) | Nelly Hoffmann (m. 1913) |

| Children | Franziska, Markus, Christoph, Matthias and Hans Jakob |

| Tradition or movement | Reformed Neo-Orthodoxy |

| Notable ideas | Dialectical theology analogia fidei |

Karl Barth, a renowned Swiss theologian, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2025. Considered as one of the most influential theologians of the 20th century, Barth's work has had a significant impact on Christian theology. His writings, such as the monumental "Church Dogmatics," continue to be widely studied by scholars and theologians around the world. Despite his contributions to theology, Barth's net worth is modest, reflecting his focus on intellectual pursuits rather than financial gain.

Karl Barth was born on May 10, 1886, in Basel, Switzerland, to Johann Friedrich "Fritz" Barth and Anna Katharina (Sartorius) Barth. Fritz Barth was a theology professor and pastor who would greatly influence his son's life. In particular, Fritz Barth was fascinated by philosophy, especially the implications of Friedrich Nietzsche's theories on free will. Barth spent his childhood years in Bern. One of the places at which he studied was Marburg University, where he was taught for a year by the Jewish Kantian thinker, Hermann Cohen. From 1911 to 1921 he served as a Reformed pastor in the village of Safenwil in the canton of Aargau. In 1913 he married Nelly Hoffmann, a talented Violinist. They had a daughter and four sons, one of whom was the New Testament scholar Markus Barth (October 6, 1915 – July 1, 1994). Later he was professor of theology in Göttingen (1921–1925), Münster (1925–1930) and Bonn (1930–1935) (Germany). While serving at Göttingen he met Charlotte von Kirschbaum, who became his long-time secretary and assistant; she played a large role in the writing of his epic, the Church Dogmatics. He had to leave Germany in 1935 after he refused to swear allegiance to Adolf Hitler and went back to Switzerland and became a professor in Basel (1935–1962).

The most important catalyst, however, was Barth's reaction to the support that most of his liberal teachers voiced for German war aims. The 1914 "Manifesto of the Ninety-Three German Intellectuals to the Civilized World" carried the signature of his former Teacher Adolf von Harnack. Barth believed that his teachers had been misled by a theology which tied God too closely to the finest, deepest expressions and experiences of cultured human beings, into claiming Divine support for a war which they believed was waged in support of that culture – the initial experience of which appeared to increase people's love of and commitment to that culture. Much of Barth's early theology can be seen as a reaction to the theology of Friedrich Schleiermacher.

Barth first began his commentary The Epistle to the Romans (Ger. Der Römerbrief) in the summer of 1916 while he was still a pastor in Safenwil, with the first edition appearing in December 1918 (but with a publication date of 1919). On the strength of the first edition of the commentary, Barth was invited to teach at the University of Göttingen. Barth decided around October 1920 that he was dissatisfied with the first edition and heavily revised it the following eleven months, finishing the second edition around September 1921. Particularly in the thoroughly re-written second edition of 1922, Barth argued that the God who is revealed in the cross of Jesus challenges and overthrows any attempt to ally God with human cultures, achievements, or possessions. The book's popularity led to its republication and reprinting in several languages.

Charlotte von Kirschbaum was Barth's secretary and theological assistant for more than three decades. When Barth first met her in 1924 he had already been married for 12 years and, in 1929, she moved into the Barth family household, which included his wife Nelly and five children. George Hunsinger summarizes the influence of von Kirschbaum on Barth's work: "As his unique student, critic, researcher, adviser, collaborator, companion, assistant, spokesperson, and confidante, Charlotte von Kirschbaum was indispensable to him. He could not have been what he was, or have done what he did, without her."

In 1934, as the Protestant Church attempted to come to terms with the Third Reich, Barth was largely responsible for the writing of the Barmen declaration (Ger. Barmer Erklärung). This declaration rejected the influence of Nazism on German Christianity by arguing that the Church's allegiance to the God of Jesus Christ should give it the impetus and resources to resist the influence of other lords, such as the German Führer, Adolf Hitler. Barth mailed this declaration to Hitler personally. This was one of the founding documents of the Confessing Church and Barth was elected a member of its leadership council, the Bruderrat.

He was forced to resign from his professorship at the University of Bonn in 1935 for refusing to swear an oath to Hitler. Barth then returned to his native Switzerland, where he assumed a chair in systematic theology at the University of Basel. In the course of his appointment he was required to answer a routine question asked of all Swiss civil servants: whether he supported the national defense. His answer was, "Yes, especially on the northern border!" The newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung carried his 1936 criticism of Martin Heidegger for his support of the Nazis. In 1938 he wrote a letter to a Czech colleague Josef Hromádka in which he declared that Soldiers who fought against the Third Reich were serving a Christian cause.

After the end of the Second World War, Barth became an important voice in support both of German penitence and of reconciliation with churches abroad. Together with Hans-Joachim Iwand, he authored the Darmstadt Statement in 1947 – a more concrete statement of German guilt and responsibility for the Third Reich and Second World War than the 1945 Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt. In it, he made the point that the Church's willingness to side with anti-socialist and conservative forces had led to its susceptibility for National Socialist ideology. In the context of the developing Cold War, that controversial statement was rejected by anti-Communists in the West who supported the CDU course of re-militarization, as well as by East German dissidents who believed that it did not sufficiently depict the dangers of Communism. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1950. In the 1950s, Barth sympathized with the peace movement and opposed German rearmament.

Barth wrote a 1960 article for The Christian Century regarding the "East-West question" in which he denied any inclination toward Eastern communism and stated he did not wish to live under Communism or wish anyone to be forced to do so; he acknowledged a fundamental disagreement with most of those around him, writing: "I do not comprehend how either politics or Christianity require [sic] or even permit such a disinclination to lead to the conclusions which the West has drawn with increasing sharpness in the past 15 years. I regard anticommunism as a matter of principle an evil even greater than communism itself."

Princeton Theological Seminary, where Barth lectured in 1962, houses the Center for Barth Studies, which is dedicated to supporting scholarship related to the life and theology of Karl Barth. The Barth Center was established in 1997 and sponsors seminars, conferences, and other events. It also holds the Karl Barth Research Collection, the largest in the world, which contains nearly all of Barth's works in English and German, several first editions of his works, and an original handwritten manuscript by Barth.

Barth died on December 10, 1968, at his home in Basel, Switzerland. The evening before his death, he had encouraged his lifelong friend Eduard Thurneysen that he should not be downhearted, "For things are ruled, not just in Moscow or in Washington or in Peking, but things are ruled – even here on earth—entirely from above, from heaven above.”

The long-standing work relationship was not without its difficulties. It caused offense among some of Barth's friends, as well as his mother. While Nelly supplied the household and the children, von Kirschbaum and Barth shared an academic relationship. The feminist scholar, Suzanne Selinger says "[p]art of any realistic response to the subject of Barth and von Kirschbaum must be anger", because she has been largely unrecognized by Barthian scholars for her work. Barth lauds von Kirschbaum for her assistance in the preface of Church Dogmatics: Volume 3 – The Doctrine of Creation Part 3.

An article written in 2017 by Christiane Tietz (originally a paper she delivered at the 2016 American Academy of Religion in San Antonio, Texas) for the academic journal Theology Today engages letters released in both 2000 and 2008 written by Barth, Charlotte von Kirschbaum, and Nelly Barth, which discuss the complicated relationship between all three individuals that occurred over the span of 40 years. The letters published in 2008 between von Kirschbaum and Barth from 1925-1935 made public "the deep, intense, and overwhelming love between these two human beings."

The relationship between Barth, liberalism, and fundamentalism goes far beyond the issue of inerrancy, however. From Barth's perspective, liberalism, as understood in the sense of the 19th century with Friedrich Schleiermacher and Hegel as its leading exponents and not necessarily expressed in any particular political ideology, is the divinization of human thinking. This, to him, inevitably leads one or more philosophical concepts to become the false God, thus attempting to block the true voice of the living God. This, in turn, leads to the captivity of theology by human ideology. In Barth's theology, he emphasizes again and again that human concepts of any kind, breadth or narrowness quite beside the point, can never be considered as identical to God's revelation. In this aspect, Scripture is also written human language, which bears witness to the self-revelation of God in Jesus Christ. Scripture cannot be considered as identical to God's self-revelation, which is properly only Jesus Christ. However, in his freedom and love, God truly reveals himself through human language and concepts, with a view toward their necessity in reaching fallen humanity. Thus Barth claims that Christ is truly presented in Scripture and the preaching of the church, echoing a stand expressed in his native Swiss Reformed Church's Helvetic Confession of the 16th century.