| Who is it? | A Member of National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) |

| Birth Day | February 12, 1885 |

| Birth Place | Fleinhausen, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire, German |

| Age | 134 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 16 October 1946(1946-10-16) (aged 61)\nNuremberg\nAmerican Zone of Occupation\nGermany |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Leader | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Hans Zimmermann (Acting, 1940) Karl Holz (acting from 1942, permanent from 1944) |

| Political party | Nazi Party |

| Spouse(s) | Kunigunde Roth (m. 1913, died 1943) Adele Tappe (m. 1945) |

| Children | Lothar Elmar |

| Profession | Publisher of propaganda |

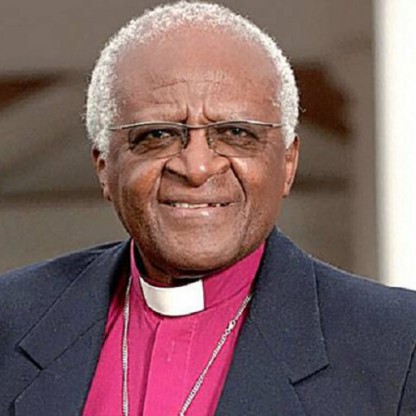

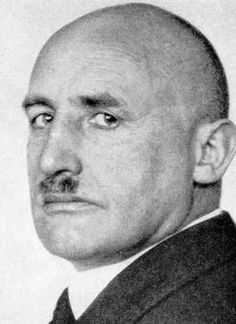

Julius Streicher, a prominent figure in the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) in Germany, is reported to have an estimated net worth of $4 million in 2025. Streicher was known for his staunch loyalty to Adolf Hitler and his propaganda efforts that targeted Jewish people during the Nazi regime. As the publisher of the antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer, he played a significant role in spreading hateful ideologies. Despite his controversial actions, Streicher rose to prominence within the Nazi party and amassed considerable wealth. His estimated net worth serves as a reminder of the financial benefits some individuals obtained from their involvement in the NSDAP.

It was on a winter's day in 1922. I sat unknown in the large hall of the Bürgerbräuhaus...suspense was in the air. Everyone seemed tense with excitement, with anticipation. Then suddenly a shout. "Hitler is coming!" Thousands of men and women jumped to their feet as if propelled by a mysterious power...they shouted, "Heil Hitler! Heil Hitler!"...And then he stood on the podium...Then I knew that in this Adolf Hitler was someone extraordinary...Here was one who could wrest out of the German spirit and the German heart the power to break the chains of slavery. Yes! Yes! This man spoke as a messenger from heaven at a time when the gates of hell were opening to pull down everything. And when he finally finished, and while the crowd raised the roof with the singing of the "Deutschland" song, I rushed to the stage.

Streicher was born in Fleinhausen, in the Kingdom of Bavaria, one of nine children of the Teacher Friedrich Streicher and his wife Anna (née Weiss). He worked as an elementary school Teacher like his father. In 1913, Streicher married Kunigunde Roth, a baker's daughter, in Nuremberg. They had two sons, Lothar (born 1915) and Elmar (born 1918).

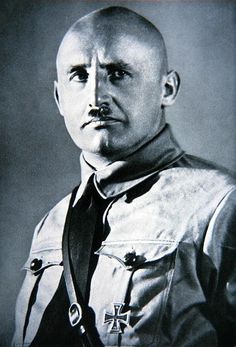

Streicher joined the German Army in 1914. For his outstanding combat performance during the First World War, he was awarded the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class, as well as earning a battlefield commission as an officer (lieutenant), despite having several reported instances of poor behavior in his military record, and at a time when officers were primarily from aristocratic families. Following the end of World War I, Streicher was demobilized and returned to Nuremberg. Upon his return, Steicher took up another teaching position there but something unknown happened in 1919, which turned him into a "radical anti-Semite."

By the end of 1919, the DSP had branches in Düsseldorf, Kiel, Frankfurt am Main, Dresden, Nuremberg and Munich. Streicher sought to move the German Socialists in a more virulently anti-Semitic direction – an effort which aroused enough opposition that he left the group and brought his now-substantial following to yet another organization in 1921, the Deutsche Werkgemeinschaft (German Working Community), which hoped to unite the various anti-Semitic völkisch movements. Meanwhile, Streicher's rhetoric against the Jews continued to intensify to such a degree that the leadership of the Deutsche Werkgemeinschaft thought he was dangerous and criticized him for his obsessive "hatred of the Jews and foreign races."

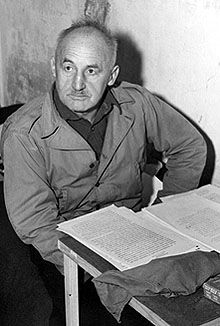

During his trial, Streicher displayed for the last time the flair for courtroom theatrics that had made him famous in the 1920s. He answered questions from his own defence attorney with diatribes against Jews, the Allies, and the court itself, and was frequently silenced by the court officers. Streicher was largely shunned by all of the other Nuremberg defendants. He also peppered his testimony with references to passages of Jewish texts he had so often carefully selected and inserted into the pages of Der Stürmer.

In 1921 Streicher joined the Nazi Party, bringing with him enough members of the German-Socialist Party to almost double the size of the Nazi Party overnight. He would later claim that because his political work brought him into contact with German Jews, he "must therefore have been fated to become later on, a Writer and speaker on racial politics". He visited Munich in order to hear Adolf Hitler speak, an experience that he later said left him transformed. When asked about that moment, Streicher stated:

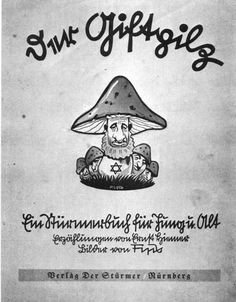

In May 1923 Streicher founded the sensationalist popular newspaper Der Stürmer (The Stormer, or, loosely, The Attacker). From the outset, the chief aim of the paper was to promulgate anti-Semitic propaganda; the first issue had an excerpt that stated, "As long as the Jew is in the German household, we will be Jewish slaves. Therefore he must go". Historian Richard J. Evans describes the newspaper:

Beginning in 1924, Streicher used Der Stürmer as a mouthpiece not only for general antisemitic attacks, but for calculated smear campaigns against specific Jews, such as the Nuremberg city official Julius Fleischmann, who worked for Streicher's nemesis, mayor Hermann Luppe. Der Stürmer accused Fleischmann of stealing socks from his quartermaster during combat in World War I. Fleischmann sued Streicher and disproved the allegations in court, where Streicher was fined 900 marks but the detailed testimony exposed less-than-glorious details of Fleischmann's record, and his reputation was badly damaged. It was proof that Streicher's unofficial motto for his tactics was correct: "Something always sticks." Der Stürmer's infamous official slogan, Die Juden sind unser Unglück (the Jews are our misfortune) was deemed non-actionable under German statutes, since it was not a direct incitement to violence.

As a reward for Streicher's dedication, when the Nazi Party was again legalized and re-organized in 1925, Streicher was appointed Gauleiter (regional leader) of the Bavarian region of Franconia, which included his home town of Nuremberg. In the early years of the party’s rise, Gauleiter were essentially party functionaries without real power; but in the final years of the Weimar Republic, as the Nazi Party grew, so did their power. During the 12 years of the Nazi regime, Gauleiters such as Streicher would wield immense power and authority, both over party matters and civil ones.

In April 1933, after Nazi control of the German state apparatus gave the Gauleiters enormous power, Streicher organised a one-day boycott of Jewish businesses which was used as a dress-rehearsal for other anti-Semitic commercial measures. As he consolidated his hold on power, he came to more or less rule the city of Nuremberg and his Gau Franken, and boasted that every Jew had been removed from Hersbruck. Among the nicknames provided by his enemies were "King of Nuremberg" and the "Beast of Franconia." Because of his role as Gauleiter of Franconia, he also gained the nickname of Frankenführer.

Streicher later claimed that he was only "indirectly responsible" for passage of the anti-Jewish Nuremberg Laws of 1935, and that he felt slighted because he was not directly consulted. Perhaps epitomizing the "profound anti-intellectualism" of the Nazi party, Streicher once opined that, "If the brains of all university professors were put at one end of the scale, and the brains of the Führer at the other, which end do you think would tip?"

Despite his special relationship with Hitler, after 1938 Streicher's position began to unravel. He was accused of keeping Jewish property seized after Kristallnacht in November 1938; he was charged with spreading untrue stories about Göring – such as alleging that Göring's daughter Edda was conceived by artificial insemination; and he was confronted with his excessive personal behaviour, including unconcealed adultery, several furious Verbal attacks on other Gauleiters and striding through the streets of Nuremberg cracking a bullwhip. In February 1940 he was stripped of his party offices and withdrew from the public eye, although he was permitted to continue publishing Der Stürmer. Hitler remained committed to Streicher, whom he considered a loyal friend, despite his unsavory reputation.

After falling out with Hermann Göring in 1939, Streicher was declared unfit for leadership by a Nazi Party Court and stripped of his party posts, although he continued to publish Der Stürmer, which was not an official Party publication.

Streicher's wife, Kunigunde Streicher, died in 1943 after 30 years of marriage.

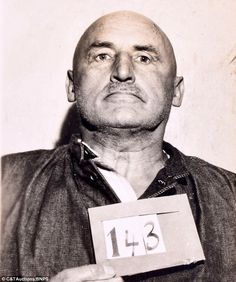

When Germany surrendered to the Allied armies in May 1945, Streicher said later, he decided to commit suicide. Instead, he married his former secretary, Adele Tappe. Days later, on 23 May 1945, Streicher was captured in the town of Waidring, Austria, by a group of American officers led by Major Henry Plitt.

Streicher was hanged at Nuremberg Prison in the early hours of 16 October 1946, along with the nine other condemned defendants from the first Nuremberg trial. Göring, Streicher's nemesis, committed suicide only hours earlier. Streicher's was the most melodramatic of the hangings carried out that night. At the bottom of the scaffold he cried out "Heil Hitler!". When he mounted the platform, he delivered his last sneering reference to Jewish scripture, snapping "Purimfest!" Streicher's final declaration before the hood went over his head was, "The Bolsheviks will hang you one day!" Joseph Kingsbury-Smith, a Journalist for the International News Service who covered the executions, said in his filed report that after the hood descended over Streicher's head, he also apparently said "Adele, meine liebe Frau!" ("Adele, my dear wife!").

During his trial, Streicher claimed that he had been mistreated by Allied Soldiers after his capture. Streicher was not a member of the military and did not take part in planning the Holocaust, or the invasion of other nations, yet his pivotal role in inciting the extermination of Jews was significant enough, in the prosecutors' judgment, to include him in the indictment of Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal – which sat in Nuremberg, where Streicher had once been an unchallenged authority. He complained throughout the process that all his judges were Jews. Most of the evidence against Streicher came from his numerous speeches and articles over the years. In essence, prosecutors contended that Streicher's articles and speeches were so incendiary that he was an accessory to murder, and therefore as culpable as those who actually ordered the mass extermination of Jews. They further argued that he kept them up his anti=Semitic propaganda even after he was aware that Jews were being slaughtered.