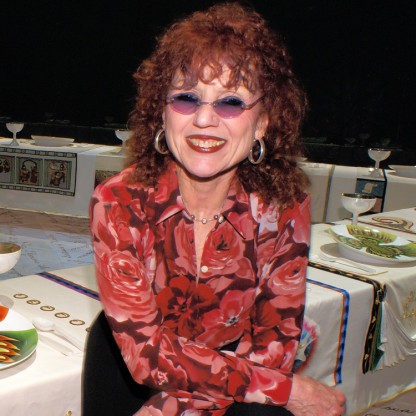

| Who is it? | American artist |

| Birth Day | July 20, 1939 |

| Birth Place | Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Age | 84 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Alma mater | University of California, Los Angeles |

| Known for | Installation Painting Sculpture |

| Notable work | The Dinner Party International Honor Quilt The Birth Project Powerplay The Holocaust Project |

| Movement | Contemporary Feminist art |

| Awards | Tamarind Fellowship, 1972 |

| Patron(s) | Holly Harp Elizabeth A. Sackler |

Judy Chicago, an acclaimed American artist, has garnered significant recognition and success throughout her career. As of 2025, her net worth is estimated to be $1.5 million. Chicago's contributions to the art world have made her a prominent figure within the United States. Her innovative and provocative works have challenged the traditional male-dominated art scene, advocating for gender equality and women's empowerment. Through her unparalleled talent, Chicago has created a lasting impact on the art industry, cementing her status as a trailblazer and a source of inspiration for aspiring artists worldwide.

Judy Chicago was born Judith Sylvia Cohen in 1939, to Arthur and May Cohen, in Chicago, Illinois. Her father came from a twenty-three generation lineage of rabbis, including the Vilna Gaon. Unlike his family predecessors, Arthur became a labor organizer and a Marxist. He worked nights at a post office and took care of Chicago during the day, while May, who was a former Dancer, worked as a medical secretary. Arthur's active participation in the American Communist Party, liberal views towards women and support of worker's rights strongly influenced Chicago's ways of thinking and belief. During the McCarthyism era in the 1950s, Arthur was investigated, which made it difficult for him to find work and caused the family much turmoil. In 1945, while Chicago was alone at home with her infant brother, Ben, an FBI agent visited their house. The agent began to ask the six-year-old Chicago questions about her father and his friends, but the agent was interrupted upon the return of May to the house. Arthur's health declined, and he died in 1953 from peritonitis. May would not discuss his death with her children and did not allow them to attend the funeral. Chicago did not come to terms with his death until she was an adult; in the early 1960s she was hospitalized for almost a month with a bleeding ulcer attributed to unresolved grief.

While at UCLA, she became politically active, designing posters for the UCLA NAACP chapter and eventually became its corresponding secretary. In June 1959, she met and became romantically linked with Jerry Gerowitz. She left school and moved in with him, for the first time having her own studio space. The couple hitch hiked to New York in 1959, just as Chicago's mother and brother moved to Los Angeles to be closer to her. The couple lived in Greenwich Village for a time, before returning in 1960 from Los Angeles to Chicago so she could finish her degree. Chicago married Gerowitz in 1961. She graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1962 and was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society. Gerowitz died in a car crash in 1963, devastating Chicago and causing her to suffer from an identity crisis until later that decade. She received her Master of Fine Arts from UCLA in 1964.

As Chicago made a name for herself as an Artist and came to know herself as a woman, she no longer felt connected to her last name, Cohen. This was due to the late grief of the death of her father and the lost connection to her name through marriage, Judith Gerowitz, after her husband's death. She decided she wanted to change her last name to something independent of being connected to a man by marriage or heritage. During this time, she married Sculptor Lloyd Hamrol, in 1965. (They divorced in 1979.) Gallery owner Rolf Nelson nicknamed her "Judy Chicago" because of her strong personality and thick Chicago accent. She decided this would be her new name, and sought to change it legally. She changed her last name from an ethnically charged, Gerowitz, to an ethnically neutral Chicago. In doing so, she freed herself from a certain social identity. Chicago was described as being "appalled" by the fact that she had to have her new husband's signature on the paperwork to change her name legally. To celebrate the name change, she posed for the exhibition invitation dressed like a boxer, wearing a sweatshirt with her new last name on it. She also posted a banner across the gallery at her 1970 solo show at California State University at Fullerton, that read: "Judy Gerowitz hereby divests herself of all names imposed upon her through male social dominance and chooses her own name, Judy Chicago." An advertisement with the same statement was also placed in Artforum's October 1970 issue.

In 1969, the Pasadena Art Museum exhibited a series of Chicago's spherical acrylic plastic dome sculptures and drawings in an "experimental" gallery. Art in America noted that Chicago's work was at the forefront of the conceptual art movement, and the Los Angeles Times described the work as showing no signs of "theoretical New York type art." Chicago would describe her early artwork as minimalist and as her trying to be "one of the boys". Chicago would also experiment with performance art, using fireworks and pyrotechnics to create "atmospheres", which involved flashes of colored smoke being manipulated outdoors. Through this work she attempted to "feminize" and "soften" the landscape.

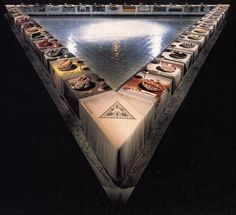

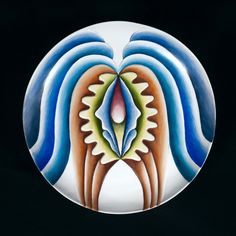

Chicago decided to take Lerner's lesson to heart and took action to teach women about their history. This action would become Chicago's masterpiece, The Dinner Party, now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum. It took her five years and cost about $250,000 to complete. First, Chicago conceived the project in her Santa Monica studio: a large triangle, which measures 48-feet by 43-feet by 36-feet, consisting of 39 place settings. Each place setting commemorates a historical or mythical female figure, such as artists, goddesses, Activists and martyrs. The project came into fruition with the assistance of over 400 people, mainly women, who volunteered to assist in needlework, creating sculptures and other aspects of the process. When The Dinner Party was first constructed it was a traveling exhibition. Through the Flower, her non-profit organization, was originally created to cover the expense of the creation and travel of the artwork. Jane Gerhard dedicated a book to Judy Chicago and The Dinner Party, entitled "The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and The Power of Popular Feminism, 1970-2007".

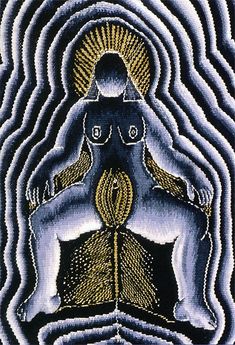

Womanhouse was a project that involved Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. It began in the fall of 1971. They wanted to start the year with a large scale collaborative project that involved woman artists who spent much of their time talking about their problems as women. They used those problems as fuel and dealt with them while working on the project. Judy thought that female students often approach art-making with an unwillingness to push their limits due to their lack of familiarity with tools and processes, and an inability to see themselves as working people. “The aim of the Feminist Art Program is to help women restructure their personalities to be more consistent with their desires to be artists and to help them build their art-making out of their experiences as women.” Womanhouse is a "true" dramatic representation of woman's experience beginning in childhood, encompassing the struggles at home, with housework, menstruation, marriage, etc.

Chicago became a Teacher at the California Institute for the Arts, and was a leader for their Feminist Art Program. In 1972, the program created Womanhouse, alongside Miriam Schapiro, which was the first art exhibition space to display a female point of view in art. With Arlene Raven and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Chicago co-founded the Los Angeles Woman's Building in 1973. This art school and exhibition space was in a structure named after a pavilion at the 1893 World's Colombian Exhibition that featured art made by women from around the world. This housed the Feminist Studio Workshop, described by the founders as "an experimental program in female education in the arts. Our purpose is to develop a new concept of art, a new kind of Artist and a new art community built from the lives, feelings, and needs of women." During this period, Chicago began creating spray-painted canvas, primarily abstract, with geometric forms on them. These works evolved, using the same medium, to become more centered around the meaning of the "feminine". Chicago was strongly influenced by Gerda Lerner, whose writings convinced her that women who continued to be unaware and ignorant of women's history would continue to struggle independently and collectively.

In 1975, Chicago's first book, Through the Flower, was published; it "chronicled her struggles to find her own identity as a woman Artist."

In 1978, Chicago founded Through the Flower, a non-profit feminist art organization. The organization seeks to educate the public about the importance of art and how it can be used as a tool to emphasize women's achievements. Through the Flower also serves as the maintainer of Chicago's works, having handled the storage of The Dinner Party, before it found a permanent home at the Brooklyn Museum. The organization also maintained The Dinner Party Curriculum, which serves as a "living curriculum" for education about feminist art ideas and pedagogy. The online aspect of the curriculum was donated to Penn State University in 2011.

In the mid-1980s Chicago's interests "shifted beyond 'issues of female identity' to an exploration of masculine power and powerlessness in the context of the Holocaust." Chicago's The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985–93) is a collaboration with her husband, Photographer Donald Woodman, whom she married on New Year's Eve 1985. Although Chicago's previous husbands were both Jewish, it wasn't until she met Woodman that she began to explore her own Jewish heritage. Chicago met poet Harvey Mudd, who had written an epic poem about the Holocaust. Chicago was interested in illustrating the poem, but decided to create her own work instead, using her own art, visual and written. Chicago worked alongside her husband to complete the piece, which took eight years to finish. The piece, which documents victims of the Holocaust, was created during a time of personal loss in Chicago's life: the death of her brother Ben, from Lou Gehrig's disease, and the death of her mother from cancer.

In 1985, Chicago was remarried, to Photographer Donald Woodman. To celebrate the couple's 25th wedding anniversary, Chicago created a “Renewal Ketubah” in 2010.

In 1994, Judy Chicago started "Resolutions: A Stitch in Time" which took 6 years to complete. The public audience later got to see this project at the Museum of Art and Design in New York in 2000.

Over the next six years, Chicago created works that explored the experiences of concentration camp victims. Galit Mana of Jewish Renaissance magazine notes, "This shift in focus led Chicago to work on other projects with an emphasis on Jewish tradition", including Voices from the Song of Songs (1997), where Chicago "introduces feminism and female sexuality into her representation of strong biblical female characters."

Chicago's archives are held at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College, and her collection of women's history and culture books are held in the collection of the University of New Mexico. In 1999, Chicago received the UCLA Alumni Professional Achievement Award, and has been awarded honorary degrees from Lehigh University, Smith College, Duke University and Russell Sage College. In 2004, Chicago received a Visionary Woman Award from Moore College of Art & Design. Chicago was named a National Women's History Project honoree for Women's History Month in 2008. Chicago donated her collection of feminist art educational materials to Penn State University in 2011. She lives in New Mexico. In the fall of 2011, Chicago returned to Los Angeles for the opening of the "Concurrents" exhibition at the Getty Museum. For the exhibition, she returned to the Pomona College football field, where in the late 1960s she had held a firework-based installation, and performed the piece again.

Chicago trained herself in "macho arts," taking classes in auto body work, boat building, and pyrotechnics. Through auto body work she learned spray painting techniques and the skill to fuse color and surface to any type of media, which would become a signature of her later work. The skills learned through boat building would be used in her sculpture work, and pyrotechnics would be used to create fireworks for performance pieces. These skills allowed Chicago to bring fiberglass and metal into her sculpture, and eventually she would become an apprentice under Mim Silinsky to learn the art of porcelain painting, which would be used to create works in The Dinner Party. Chicago also added the skill of stained glass to her artistic tool belt, which she used for The Holocaust Project. Photography became more present in Chicago's work as her relationship with Photographer Donald Woodman developed. Since 2003, Chicago has been working with glass.

Chicago had two solo exhibitions in the United Kingdom in 2012, one in London and another in Liverpool. The Liverpool exhibition included the launch of Chicago's book about Virginia Woolf. Once a peripheral part of her artistic expression, Chicago now considers writing to be well integrated into her career. That year, she was also awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Palm Springs Art Fair.

The art created in the Feminist Art Program and Womanhouse introduced perspectives and content about women’s lives that had been taboo topics in society, including the art world. In 1970 Chicago developed the Feminist Art Program at California State University, Fresno, and has implemented other teaching projects that conclude with an art exhibition by students such as Womanhouse with Miriam Schapiro at CalArts, and SINsation in 1999 at Indiana University, From Theory to Practice: A Journey of Discovery at Duke University in 2000, At Home: A Kentucky Project with Judy Chicago and Donald Woodman at Western Kentucky University in 2002, Envisioning the Future at California Polytechnic State University and Pomona Arts Colony in 2004, and Evoke/Invoke/Provoke at Vanderbilt University in 2005. Several students involved in Judy Chicago’s teaching projects established successful careers as artists, including Suzanne Lacy, Faith Wilding, and Nancy Youdelman.