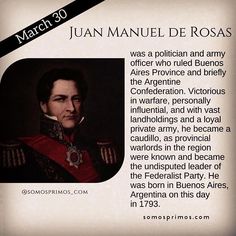

| Who is it? | Dictator of Argentina |

| Birth Day | March 30, 1793 |

| Birth Place | Buenos Aires, Argentine |

| Age | 226 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 14 March 1877(1877-03-14) (aged 83)\nSouthampton, United Kingdom |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Preceded by | Juan José Viamonte |

| Succeeded by | Juan Ramón Balcarce |

| Resting place | La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires |

| Political party | Unitarian Party (1820–26) Federalist Party (1826–52) |

| Spouse(s) | Encarnación Ezcurra |

| Children | Juan Bautista Ortiz de Rosas Manuela Robustiana Rosas |

Juan Manuel de Rosas, famously recognized as the Dictator of Argentina in the mid-19th century, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million by 2025. Rosas amassed significant wealth during his controversial reign, characterized by a strict autocratic rule. Known for his influential role in shaping Argentine politics and society, his accumulation of assets was primarily the product of his control over vast portions of the country's agricultural economy. His net worth is a testament to the profound impact he had on Argentina's history, both as a political figure and as a wealthy landowner.

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas was born on 30 March 1793 at his family's town house in Buenos Aires, the capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He was the first child of León Ortiz de Rosas and Agustina López de Osornio. León Ortiz was the son of an immigrant from the Spanish Province of Burgos. A military officer with an undistinguished career, León Ortiz had married into a wealthy Criollo family. The young Juan Manuel de Rosas's character was heavily influenced by his mother Agustina, a strong-willed and domineering woman who derived these character traits from her father Clemente López de Osornio, a landowner who died defending his estate from an Indian attack in 1783.

In 1806, a British expeditionary force invaded Buenos Aires. A 13-year-old Rosas served distributing ammunition to troops in a force organised by Viceroy Santiago Liniers to counter the invasion. The British were defeated in August 1806, but returned a year later. Rosas was then assigned to the Caballería de los Migueletes (a militia cavalry), although he was probably barred from active duty during this time due to illness.

The breakup of the old Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata during the 1810s eventually resulted in the emergence of independent nations of Paraguay, Bolivia and Uruguay in the northern portion of the Viceroyalty, while its southern territories coalesced into the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. Rosas planned to restore, if not all, at least a considerable part of the former borders of the old Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He never recognized the independence of Paraguay and regarded it a rebel Argentine province that would inevitably be reconquered. He sent an army under Manuel Oribe who invaded Uruguay and conquered most of the country, except for its capital Montevideo that endured a long siege starting in 1843. When pressed by the British, Rosas declined to guarantee Uruguayan independence. In South America, all potential foreign threats to Rosas's plans of conquest collapsed, including Gran Colombia and the Peru–Bolivian Confederation, or were troubled by internal turmoil, as was the Empire of Brazil. To reinforce his claims over Uruguay and Paraguay, and maintain his dominance over the Argentine provinces, Rosas blockaded the port of Montevideo and closed the interior rivers to foreign trade.

Rosas acquired a working knowledge of administering ranchlands and, beginning in 1811, took charge of his family's estancias. In 1813, he married Encarnación Ezcurra, daughter of a wealthy family from Buenos Aires. He soon afterwards sought to establish a career for himself, leaving his parent's estate. He produced salted meat and acquired landholdings in the process. As the years passed he became an estanciero (rancher) in his own right, accumulating land while establishing a successful partnership with second cousins from the politically powerful Anchorena clan. His hard work and organisational skills in deploying labour were key to his success, rather than creating new or applying nontraditional approaches to production.

When the Congress of Tucumán severed all remaining ties with Spain in July 1816, Rosas and his peers accepted independence as an accomplished fact. Independence resulted in a breakup of the territories that had formed the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. The province of Buenos Aires fought a civil war with the other provinces over the degree of autonomy which the provincial governments were to have. The Unitarian Party supported the preeminence of Buenos Aires, while the Federalist Party defended provincial autonomy. A decade of strife over the issue destroyed the ties between capital and provinces, with new republics being declared throughout the country. Efforts by the Buenos Aires government to quash these independent states were met with determined local resistance. In 1820 Rosas and his gauchos, all dressed in red and nicknamed "Colorados del Monte" ("Reds of the Mount"), enlisted in the army of Buenos Aires as the Fifth Regiment of Militia. They repulsed invading provincial armies, saving Buenos Aires.

Rosas' early administration was preoccupied with the severe deficits, large public debts and the impact of currency devaluation which his government inherited. A great drought that began in December 1828, which would last until April 1832, greatly impacted the economy. The Unitarians were still at large, controlling several provinces that had banded together in the Unitarian League. The capture of José María Paz, the main Unitarian leader, in March 1831 resulted in the end of the Unitarian–Federalist civil war and the collapse of the Unitarian League. Rosas was content, for the moment, to agree to recognize provincial autonomy in the Federal Pact. In an effort to alleviate the government's financial problems, he improved revenue collection while not raising taxes and curtailed expenditure.

Around 1845, Rosas managed to establish absolute dominance over the region. He exercised complete control over all aspects of society with the solid backing of the army. Rosas was raised from colonel to brigadier general (the highest army rank) on 18 December 1829. On 12 November 1840 he declined the newly created and higher rank of grand marshal (gran mariscal), which had been bestowed on him by the House of Representatives. The army was led by officers who had backgrounds and values similar to his. Confident of his power, Rosas made some concessions by returning confiscated properties to their owners, disbanding the Mazorca and ending torture and political assassinations. The inhabitants of Buenos Aires still dressed and behaved according to the set of rules Rosas had imposed, but the climate of constant and widespread fear greatly diminished.

At the end of the conflict, Rosas returned to his estancias having acquired prestige for his military Service. He was promoted to cavalry colonel and was awarded further landholdings by the government. These additions, together with his successful Business and fresh property acquisitions, greatly boosted his wealth. By 1830, he was the 10th largest landowner in the province of Buenos Aires (in which the city of the same name was located), owning 300,000 cattle and 420,000 acres (170,000 ha) of land. With his newly gained influence, military background, vast landholdings and a private army of gauchos loyal only to him, Rosas became the quintessential caudillo, as provincial Warlords in the region were known.

By the end of his first term, Rosas was generally credited with having staved off political and financial instability, but he faced increased opposition in the House of Representatives. All members of the House were Federalists, as Rosas had restored the legislature that had been in place under Dorrego, and which had subsequently been dissolved by Lavalle. A liberal Federalist faction, which accepted dictatorship as a temporary necessity, called for the adoption of a constitution. Rosas was unwilling to govern constrained by a constitutional framework and only grudgingly relinquished his dictatorial powers. His term of office ended soon after, on 5 December 1832.

While the government in Buenos Aires was distracted with political infighting, ranchers began moving into territories in the south inhabited by indigenous peoples. The resulting conflict with native peoples necessitated a government response. Rosas steadfastly endorsed policies which supported this expansion. During his governorship he granted lands in the south to war veterans and to ranchers seeking alternative pasture lands during the drought. Although the south was regarded as a virtual desert at the time, it had great potential and resources for agricultural development, particularly for ranching operations. The government gave Rosas command of an army with orders to subdue the Indian tribes in the coveted territory. Rosas was generous to those Indians who surrendered, rewarding them with animals and goods. Although he personally disliked killing Indians, he relentlessly hunted down those who refused to yield. The Desert Campaign lasted from 1833 to 1834, with Rosas subjugating the entire region. His conquest of the south opened up many possibilities for further territorial expansion, which led him to state: "The fine territories, which extend from the Andes to the coast and down to the Magellan Straits are now wide open for our children."

When Rosas was elected governor for the first time in 1829, he held no power outside the province of Buenos Aires. There was no national government or national parliament. The former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata had been succeeded by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, which by 1831, following the Federal Pact and officially from 22 May 1835, had increasingly been known as the Argentine Confederation, or simply, Argentina. Rosas's victory over the other Argentine provinces in the early 1840s turned them into satellites of Buenos Aires. He gradually put in place provincial governors who were either allied or too weak to have real independence, which allowed him to exercise dominance over all the provinces. By 1848, Rosas began calling his government the "government of the confederacy" and the "general government", which would have been inconceivable a few years before. The next year, with acquiescence of the provinces, he named himself "Supreme Head of the Confederacy" and became the indisputable ruler of Argentina.

Throughout the late 1830s and early 1840s, Rosas faced a series of major threats to his power. The Unitarians found an ally in Andrés de Santa Cruz, the ruler of the Peru–Bolivian Confederation. Rosas declared war against the Peru–Bolivian Confederation on 19 March 1837, joining the War of the Confederation between Chile and Peru–Bolivia. The Rosista army played a minor role in the conflict, which resulted in the overthrow of Santa Cruz and the dissolution of the Peru–Bolivian Confederation. On 28 March 1838, France declared a blockade of the Port of Buenos Aires, eager to extend its influence over the region. Unable to confront the French, Rosas increased internal repression to forestall potential uprisings against his regime.

As Rosas aged and his health declined, the question of who would succeed him became a growing concern among his supporters. His wife Encarnación had died in October 1838 after a long illness. Although devastated by his loss, Rosas exploited her death to raise support for his regime. Not long after, at the age of 47, he began an affair with his fifteen-year-old maid, María Eugenia Castro, with whom he had five illegitimate children. From his marriage to Encarnación, Rosas had two children: Juan Bautista Pedro and Manuela Robustiana. Rosas established a hereditary dictatorship, naming the children from his marriage as his successors, stating that "[t]hey are both worthy children of my beloved Encarnación, and if, God willing, I die, then you will find that they are capable of succeeding me." It is unknown whether Rosas was a closet monarchist. Later during his exile, Rosas would declare that Princess Alice of the United Kingdom would be the ideal ruler for his country. Nonetheless, in public he stated that his regime was republican in nature.

The blockade caused severe damage to the economy across all the provinces, as they exported their goods through the port of Buenos Aires. Despite the 1831 Federal Pact, all provinces had long been discontent with the de facto primacy that Buenos Aires province held over them. On 28 February 1839, the province of Corrientes revolted and attacked both Buenos Aires and Entre Ríos provinces. Rosas counterattacked and defeated the rebels, killing their leader, the governor of Corrientes. In June, Rosas uncovered a plot by dissident Rosistas to oust him from power in what became known as the Maza conspiracy. Rosas imprisoned some of the plotters and executed others. Manuel Vicente Maza, President of both the House of Representatives and the Supreme Court, was murdered by Rosas's Mazorca agents within the halls of the parliament on the pretext that his son was involved in the conspiracy. In the countryside, estancieros, including a younger brother of Rosas, revolted, beginning the Rebellion of the South. The rebels attempted to ally with France, but were easily crushed, many losing their lives and properties in the process.

Rosas failed to realize that discontent was steadily growing throughout the country. Throughout the 1840s he became increasingly secluded in his country house in Palermo, some miles away from Buenos Aires. There he ruled and lived under heavy protection provided by guards and patrols. He declined to meet with his ministers and relied solely on Secretaries. His daughter Manuela replaced his wife at his right hand and became the link between Rosas and the outside world. The reason for Rosas's increasing isolation was given by a member of his secretariat: "The dictator is not stupid: he knows the people hate him; he goes in constant fear and always has one eye on the chance to rob and abuse them and the other on making a getaway. He has a horse ready saddled at the door of his office day and night".

The loss of trade was unacceptable to Britain and France. On 17 September 1845 both nations established the Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata and enforced the free navigation in the Río de la Plata Basin (or Platine region). Argentina resisted the pressure and fought back to a standstill. This undeclared war caused more economic harm to France and Britain than to Argentina. The British faced increasing pressure at home once they realised that the access gained to the other ports within the Platine region did not compensate for the loss of trade with Buenos Aires. Britain ended all hostilities and lifted the blockade on 15 July 1847, followed by France on 12 June 1848. Rosas had successfully resisted the two most powerful nations on Earth; his standing, and Argentina's, increased among Hispanic American nations. The Venezuelan humanist Andrés Bello, summarizing the prevailing opinion, considered Rosas among "the leading ranks of the great men of America".

Although his prestige was on the rise, Rosas made no serious attempts to further liberalise his regime. Every year he presented his resignation and the pliant House of Representatives predictably declined, claiming that maintaining him in office was vital for the nation's welfare. Rosas also allowed exiled Argentines to return to their homeland, but only because he was so confident of his control and that no one was willing to risk defying him. The execution in August 1848 of the pregnant young Camila O'Gorman, charged with a forbidden romance with a priest, caused a backlash throughout the continent. Nonetheless, it served as a clear warning that Rosas had no intention of loosening his grip.

Meanwhile, Brazil, now ascendant under Emperor Dom Pedro II, provided support to the Uruguayan government that still held out in Montevideo, as well as to the ambitious Justo José de Urquiza, a caudillo in Entre Ríos who rebelled against Rosas. Once one of Rosas' most trusted lieutenants, Urquiza now claimed to fight for a constitutional government, although his ambition to become head of state was barely disguised. In retaliation, Rosas declared war on Brazil on 18 August 1851, beginning the Platine War. The army under Oribe in Uruguay surrendered to Urquiza in October. With arms and financial aid given by Brazil, Urquiza then marched through Argentine territory heading to Buenos Aires.

Rosas arrived in Plymouth, Great Britain, on 26 April 1852. The British gave him asylum, paid for his travel and welcomed him with a 21-gun salute. These honours were granted because, according to the British Foreign Secretary James Harris, 3rd Earl of Malmesbury, "General Rosas was no Common refugee, but one who had shown great distinction and kindness to the British merchants who had traded with his country". Months before his fall, Rosas had arranged with the British chargé d'affaires Captain Robert Gore for protection and asylum in the event of his defeat. Both his children by Encarnación followed him into exile, although Juan Bautista soon returned with his family to Argentina. His daughter Manuela married the son of an old associate of Rosas, an act which the former dictator never forgave. A domineering father, Rosas wanted his daughter to remain devoted to him alone. Although he forbade her from writing or visiting, Manuela remained loyal to him and maintained contact.

In exile Rosas was not destitute, but he lived modestly amid financial constraints during the remainder of his life. A very few loyal friends sent him money, but it was never enough. He sold one of his estancias before the confiscation and became a tenant farmer in Swaythling, near Southampton. He employed a housekeeper and two to four laborers, to whom he paid above-average wages. Despite constant concern over his shortage of funds, Rosas found joy in farm life, once remarking: "I now consider myself happy on this farm, living in modest circumstances as you see, earning a living the hard way by the sweat of my brow". A contemporary described him in final years: "He was then eighty, a man still handsome and imposing; his manners were most refined, and the modest environment did nothing to lessen his air of a great lord, inherited from his family." After a walk on a cold day, Rosas caught pneumonia and died at 07:00 on the morning of 14 March 1877. Following a private mass attended by his family and a few friends, he was buried in the town cemetery of Southampton.

Serious attempts to reassess Rosas's reputation began in the 1880s with the publication of scholarly works by Adolfo Saldías and Ernesto Quesada. Later, a more blatant "Revisionist" movement would flourish under Nacionalismo (Nationalism). Nacionalismo was a political movement that appeared in Argentina in the 1920s and reached its apex in the 1930s. It was the Argentine equivalent of the authoritarian ideologies that arose during the same period, such as Nazism, Fascism and Integralism. Argentine Nationalism was an authoritarian, anti-Semitic, racist and misogynistic political movement with support for racially based pseudo-scientific theories such as eugenics. Revisionismo (Revisionism) was the historiographical wing of Argentine Nacionalismo. The main goal of Argentine Nacionalismo was to establish a national dictatorship. For the Nacionalismo movement, Rosas and his regime were idealized and portrayed as paragons of governmental virtue. Revisionismo served as a useful tool, as the main purpose of the revisionists within the Nacionalismo agenda was to rehabilitate Rosas's image.

Despite a decades-long struggle, Revisionismo failed to be taken seriously. According to Michael Goebel, the revisionists had a "lack of interest in scholarly standards" and were known for "their institutional marginality in the intellectual field". They also never succeeded in changing mainstream views regarding Rosas. william Spence Robertson said in 1930: "Among the enigmatical personages of the 'Age of Dictators' in South America none played a more spectacular role than the Argentine dictator, Juan Manuel de Rosas, whose gigantic and ominous figure bestrode the Plata River for more than twenty years. So despotic was his power that Argentine Writers have themselves styled this age of their history as 'The Tyranny of Rosas'." In 1961, william Dusenberry said: "Rosas is a negative memory in Argentina. He left behind him the black legend of Argentine history—a legend which Argentines in general wish to forget. There is no monument to him in the entire nation; no park, plaza, or street bears his name."

In the 1980s, Argentina was a fractured, deeply divided nation, having faced military dictatorships, severe economic crises and a defeat in the Falklands War. President Carlos Menem decided to repatriate Rosas's remains and take advantage of the occasion to unite the Argentines. Menem believed that if the Argentines could forgive Rosas and his regime, they might do the same regarding the more recent and vividly remembered past. On 30 September 1989, an elaborate and enormous cortege organized by the government was held, after which the remains of the Argentine ruler were interred in his family vault at La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires. Closely allied with neorevisionists, Menem (and his fellow Peronist presidential successors Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner) have honoured Rosas on banknotes, postage stamps and monuments, causing mixed reactions among the public. Rosas remains a controversial figure among Argentines, who "have long been fascinated and outraged" by him, as Historian John Lynch noted.

National unity crumbled under the weight of a continuous round of civil wars, rebellions and coups. The Unitarian–Federalist struggle brought perennial instability while caudillos fought for power and laid waste to the countryside. By 1826, Rosas had built a power base, consisting of relatives, friends and clients, and joined the Federalist Party. He remained a strong advocate of his native province of Buenos Aires, with little concern for political ideology. In 1820, Rosas fought alongside the Unitarians because he saw the Federalist invasion as a menace to Buenos Aires. When the Unitarians sought to appease the Federalists by proposing to grant the other provinces a share in the customs revenues flowing through Buenos Aires, Rosas saw this as a threat to his province's interests. In 1827, four provinces led by Federalist caudillos rebelled against the Unitarian government. Rosas was the driving force behind the Federalist takeover of Buenos Aires and the election of Manuel Dorrego as provincial governor that year. Rosas was awarded with the post of general commander of the rural militias of the province of Buenos Aires on 14 July, which increased his influence and power.

The new Argentine government confiscated all of Rosas' properties and tried him as a Criminal, later sentencing him to death. Rosas was appalled that most of his friends, supporters and allies abandoned him and became either silent or openly critical of him. Rosismo vanished overnight. "The landed class, supporters and beneficiaries of Rosas, now had to make their peace—and their profits—with his successors. Survival, not allegiance, was their politics", argued Lynch. Urquiza, a one-time ally and later an enemy, reconciled with Rosas and sent him financial assistance, hoping for political support in return—although Rosas had scant political capital left. Rosas followed Argentina's developments while in exile, always hoping for an opportunity to return, but he never again insinuated himself into Argentine affairs.