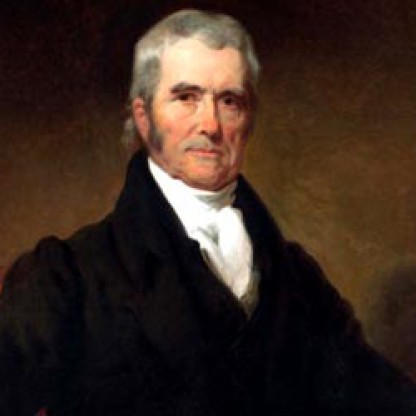

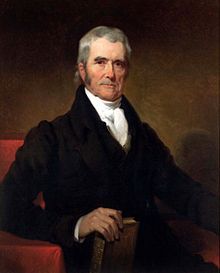

| Who is it? | Former Chief Justice |

| Birth Day | September 24, 1755 |

| Birth Place | Germantown, United States |

| Age | 264 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | July 6, 1835(1835-07-06) (aged 79)\nPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Nominated by | John Adams |

| Preceded by | John Clopton |

| Succeeded by | Littleton Tazewell |

| President | John Adams |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Willis Ambler |

| Children | 10 (including Edward) |

| Education | College of William and Mary |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/branch | Culpeper Minutemen |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

John Marshall, renowned as the former Chief Justice of the United States, is expected to have a net worth of around $9 million by the year 2025. Marshall's significant wealth can be attributed to his illustrious career in the legal field and his influential role as Chief Justice. Throughout his tenure, Marshall left a lasting impact on the nation's judicial system, shaping constitutional interpretations and strengthening the power of the federal government. His expertise and contribution to American jurisprudence have not only earned him a place in history but also a substantial personal fortune.

To say that the intention of the instrument must prevail; that this intention must be collected from its words; that its words are to be understood in that sense in which they are generally used by those for whom the instrument was intended; that its provisions are neither to be restricted into insignificance, nor extended to objects not comprehended in them, nor contemplated by its framers—is to repeat what has been already said more at large, and is all that can be necessary.

Two days before his death, Marshall enjoined his friends to place only a plain slab over his and his wife's graves, and wrote the simple inscription himself. His body, which was taken to Richmond, lies in Shockoe Hill Cemetery. The memorial inscription on his tombstone reads as follows: "Son of Thomas and Mary Marshall/was born September 24, 1755/Intermarried with Mary Willis Ambler/the 3rd of January 1783/Departed this life/the 6th day of July 1835."

In the early 1760s, the Marshall family left Germantown and moved about 30 miles (48 km) to Leeds Manor (so named by Lord Fairfax) on the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge Mountains. On the banks of Goose Creek, Thomas Marshall built a wood frame house, with two rooms on the first floor and a two-room loft above. Thomas Marshall was not yet well established, so he leased it from Colonel Richard Henry Lee. The Marshalls called their new home "the Hollow", and the ten years they resided there were John Marshall's formative years.

In 1773, the Marshall family moved once again. Thomas Marshall, by then a man of substantial means, purchased an estate adjacent to North Cobbler Mountain in Delaplane. The new farm was located adjacent to the main stage road (now US 17) between Salem (the modern day village of Marshall, Virginia) and Delaplane. When John was 17, Thomas Marshall built Oak Hill there, a seven-room frame home with four rooms on the first floor and three above. Although modest in comparison to the estates of George Washington, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson, it was a substantial home for the period. John Marshall became the owner of Oak Hill in 1785 when his father moved to Kentucky. Although John Marshall lived his later life in Richmond, Virginia, and Washington D.C., he kept his Fauquier County property, making substantial improvements to the house until he transferred the property as a wedding present to his eldest son Thomas in 1809.

Marshall served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and was friends with George Washington. He served first as a lieutenant in the Culpeper Minutemen from 1775 to 1776, and went on to serve as a lieutenant and then a captain in the Eleventh Virginia Continental Regiment from 1776 to 1780. During his time in the army, he enjoyed running races with the other Soldiers and was nicknamed Silverheels for the white heels his mother had sewn into his stockings. Marshall endured the brutal winter conditions at Valley Forge (1777–1778). After his time in the Army, he read law under the famous Chancellor George Wythe at the College of william and Mary, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and was admitted to the Bar in 1780. He was in private practice in Fauquier County before entering politics.

In 1782, Marshall won a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, in which he served until 1789 and again from 1795 to 1796. The Virginia General Assembly elected him to serve on the Council of State later in the same year. In 1785, Marshall took up the additional office of Recorder of the Richmond City Hustings Court.

Meanwhile, Marshall's private law practice continued to flourish. He successfully represented the heirs of Lord Fairfax in Hite v. Fairfax (1786), an important Virginia Supreme Court case involving a large tract of land in the Northern Neck of Virginia. In 1796, he appeared before the United States Supreme Court in another important case, Ware v. Hylton, a case involving the validity of a Virginia law providing for the confiscation of debts owed to British subjects. Marshall argued that the law was a legitimate exercise of the state's power; however, the Supreme Court ruled against him, holding that the Treaty of Paris in combination with the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution required the collection of such debts.

The Constitution does not explicitly give judicial review to the Court, and Jefferson was very angry with Marshall's position, for he wanted the President to decide whether his acts were constitutional or not. Historians mostly agree that the framers of the Constitution did plan for the Supreme Court to have some sort of judicial review; Marshall made their goals operational. Judicial review was not new and Marshall himself mentioned it in the Virginia ratifying convention of 1788. Marshall's opinion expressed and fixed in the American tradition and legal system a more basic theory—government under law. That is, judicial review means a government in which no person (not even the President) and no institution (not even Congress or the Supreme Court itself), nor even a majority of voters, may freely work their will in violation of the written Constitution. Marshall himself never declared another law of Congress or act of a President unconstitutional.

Marshall loved his home, built in 1790, in Richmond, Virginia, and spent as much time there as possible in quiet contentment. For approximately three months each year, Marshall lived in Washington during the Court's annual term, boarding with Justice Story during his final years at the Ringgold-Carroll House. Marshall also left Richmond for several weeks each year to serve on the circuit court in Raleigh, North Carolina. He also maintained the D. S. Tavern property in Albemarle County, Virginia, from 1810–1813.

Marshall himself was not religious, and although his grandfather was a priest, never formally joined a church. He did not believe Jesus was a Divine being, and in some of his opinions referred to a deist "Creator of all things." He was an active Freemason and served as Grand Master of Masons in Virginia in 1794–1795 of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of Ancient, Free, and Accepted Masons of the Commonwealth of Virginia. While in Richmond, Marshall attended St. John's Church on Church Hill until 1814 when he led the movement to hire Robert Mills as Architect of Monumental Church, which was near his home and rebuilt to commemorate 72 people who died in a theater fire. The Marshall family occupied Monumental Church's pew No. 23 and entertained the Marquis de Lafayette there during his visit to Richmond in 1824.

In 1795, Marshall declined Washington's offer of Attorney General of the United States and, in 1796, declined to serve as minister to France.

The other members of this commission were Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry. However, when the envoys arrived in October 1797, they were kept waiting for several days, and then granted only a 15-minute meeting with French Foreign Minister Talleyrand. After this, the diplomats were met by three of Talleyrand's agents. Each refused to conduct diplomatic negotiations unless the United States paid enormous bribes, one to Talleyrand personally, and another to the Republic of France. The Americans refused to negotiate on such terms. Marshall and Pinckney returned home, while Gerry remained. This diplomatic scandal became known as the XYZ Affair, inflaming anti-French opinion in the United States. Marshall arrived in New York on June 17. His handling of the affair, as well as public resentment toward the French, made him popular with the American public. He opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts, enacted by the Federalists in response to the crisis.

In 1798, Marshall declined a Supreme Court appointment, recommending Bushrod Washington, who would later become one of Marshall's staunchest allies on the Court. In 1799, Marshall reluctantly ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. Although his congressional district (which included the city of Richmond) favored the Democratic-Republican Party, Marshall won the race, in part due to his conduct during the XYZ Affair and in part due to the support of Patrick Henry. His most notable speech was related to the case of Thomas Nash (alias Jonathan Robbins), whom the government had extradited to Great Britain on charges of murder. Marshall defended the government's actions, arguing that nothing in the Constitution prevents the United States from extraditing one of its citizens.

On May 7, 1800, President Adams nominated Congressman Marshall as Secretary of War. However, on May 12, Adams withdrew the nomination, instead naming him Secretary of State, as a replacement for Timothy Pickering. Confirmed by the United States Senate on May 13, Marshall took office on June 6, 1800. As Secretary of State, Marshall directed the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which ended the Quasi-War with France and brought peace to the nation.

Marshall was thrust into the office of Chief Justice in the wake of the presidential election of 1800. With the Federalists soundly defeated and about to lose both the executive and legislative branches to Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, President Adams and the lame duck Congress passed what came to be known as the Midnight Judges Act, which made sweeping changes to the federal judiciary, including a reduction in the number of Justices from six to five (upon the next vacancy in the court) so as to deny Jefferson an appointment until two vacancies occurred. As the incumbent Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth was in poor health, Adams first offered the seat to ex-Chief Justice John Jay, who declined on the grounds that the Court lacked "energy, weight, and dignity." Jay's letter arrived on January 20, 1801, and as there was precious little time left, Adams surprised Marshall, who was with him at the time and able to accept the nomination immediately. The Senate at first delayed, hoping that Adams would make a different choice, such as promoting Justice william Paterson of New Jersey. According to New Jersey Senator Jonathan Dayton, the Senate finally relented "lest another not so qualified, and more disgusting to the Bench, should be substituted, and because it appeared that this gentleman [Marshall] was not privy to his own nomination". Marshall was confirmed by the Senate on January 27, 1801, and received his commission on January 31, 1801. While Marshall officially took office on February 4, at the request of the President he continued to serve as Secretary of State until Adams' term expired on March 4. President John Adams offered this appraisal of Marshall's impact: "My gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life."

Marshall used Federalist approaches to build a strong federal government over the opposition of the Jeffersonian Republicans, who wanted stronger state governments. His influential rulings reshaped American government, making the Supreme Court the final arbiter of constitutional interpretation. The Marshall Court struck down an act of Congress in only one case (Marbury v. Madison in 1803) but that established the Court as a center of power that could overrule the Congress, the President, the states, and all lower courts if that is what a fair reading of the Constitution required. He also defended the legal rights of corporations by tying them to the individual rights of the stockholders, thereby ensuring that corporations have the same level of protection for their property as individuals had, and shielding corporations against intrusive state governments.

Marshall greatly admired George Washington, and between 1804 and 1807 published an influential five-volume biography. Marshall's Life of Washington was based on records and papers provided to him by the late president's family. The first volume was reissued in 1824 separately as A History of the American Colonies. The work reflected Marshall's Federalist principles. His revised and condensed two-volume Life of Washington was published in 1832. Historians have often praised its accuracy and well-reasoned judgments, while noting his frequent paraphrases of published sources such as william Gordon's 1801 history of the Revolution and the British Annual Register. After completing the revision to his biography of Washington, Marshall prepared an abridgment. In 1833 he wrote, "I have at length completed an abridgment of the Life of Washington for the use of schools. I have endeavored to compress it as much as possible. ... After striking out every thing which in my judgment could be properly excluded the volume will contain at least 400 pages." The Abridgment was not published until 1838, three years after Marshall died.

The Burr trial (1807) was presided over by Marshall together with Judge Cyrus Griffin. This was the great state trial of former Vice President Aaron Burr, who was charged with treason and high misdemeanor. Prior to the trial, President Jefferson condemned Burr and strongly supported conviction. Marshall, however, narrowly construed the definition of treason provided in Article III of the Constitution; he noted that the prosecution had failed to prove that Burr had committed an "overt act", as the Constitution required. As a result, the jury acquitted the defendant, leading to increased animosity between the President and the Chief Justice.

Fletcher v. Peck (1810) was the first case in which the Supreme Court ruled a state law unconstitutional, though the Court had long before voided a state law as conflicting with the combination of the Constitution together with a treaty (Marshall had represented the losing side in that 1796 case). In Fletcher, the Georgia legislature had approved a land grant, known as the Yazoo Land Act of 1795. It was then revealed that the land grant had been approved in return for bribes, and therefore voters rejected most of the incumbents; the next legislature repealed the law and voided all subsequent transactions (even honest ones) that resulted from the Yazoo land scandal. The Marshall Court held that the state legislature's repeal of the law was void because the sale was a binding contract, which according to Article I, Section 10, Clause I (the Contract Clause) of the Constitution, cannot be invalidated. Marshall emphasized that the rescinding act would seize property from individuals who had honestly acquired it, and transfer that property to the public without any compensation. He then expanded upon his own famous statement in Marbury about the province of the judiciary:

In Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 518 (1819), the legal structure of modern corporations began to develop, when the Court held that private corporate charters are protected from state interference by the Contract Clause of the Constitution.

Cohens v. Virginia (1821) displayed Marshall's nationalism as he enforced the supremacy of federal law over state law, under the Constitution's Supremacy Clause. In this case, he established that the Federal judiciary could hear appeals from decisions of state courts in Criminal cases as well as the civil cases over which the court had asserted jurisdiction in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816). Justices Bushrod Washington and Joseph Story proved to be his strongest allies in these cases.

In 1823, Marshall became the first President of the Richmond branch of the American Colonization Society, which was dedicated to resettling freed American slaves in Liberia, on the West coast of Africa. In 1825, as Chief Justice, Marshall wrote an opinion in the case of the captured slave ship Antelope, in which he acknowledged that slavery was against natural law, but upheld the continued enslavement of approximately 1/3 of the ship's cargo (although the remainder were to be sent to Liberia). In his last will and testament, Marshall gave his elderly manservant the choice either of freedom and travel to Liberia, or continued enslavement under his choice of Marshall's children.

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) overturned a monopoly granted by the New York state legislature to certain steamships operating between New York and New Jersey. Daniel Webster argued that the Constitution, by empowering Congress to regulate interstate commerce, implied that states do not have any concurrent power to regulate interstate commerce. Chief Justice Marshall avoided that issue about the exclusivity of the federal commerce power because that issue was not necessary to decide the case. Instead, Marshall relied on an actual, existing federal statute for licensing ships, and he held that that federal law was a legitimate exercise of the congressional power to regulate interstate commerce, so the federal law superseded the state law granting the monopoly.

In 1828, Marshall presided over a convention to promote internal improvements in Virginia. The following year, Marshall was a delegate to the state constitutional convention of 1829–30, where he was again joined by fellow American statesman and loyal Virginians, James Madison and James Monroe, although all were quite old by that time (Madison was 78, Monroe 71, and Marshall 74). Although proposals to reduce the power of the Tidewater region's slave-owning aristocrats compared to growing western population proved controversial, Marshall mainly spoke to promote the necessity of an independent judiciary.

Elected as a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830, John Marshall advanced his view that the electorate should be expanded in Virginia by the provision that any white male who had served in the War of 1812 or who would serve in the militia in the Future defense of the country deserved the right to vote.

In 1831, the 76-year-old Marshall traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and underwent an operation to remove bladder stones. He recovered from it without complications, but his wife died at the end of the year and his health quickly declined from that point onward. In June 1835, Marshall again traveled to Philadelphia for medical treatment, where he died on July 6 at the age of 79, having served as Chief Justice for over 34 years.

In Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832), the Court laid out the foundations of tribal sovereignty and established the relations between the US and the Native American nations. It vacated the conviction of Samuel Worcester for being on tribal lands without a license from the Georgia, finding the state requirement to do so violated the Constitution.

In Barron v. Baltimore, 32 U.S. 243 (1833), the Court held that the Bill of Rights was intended to apply only against the federal government, and therefore does not apply against the states. The courts have since incorporated most of the Bill of Rights with respect to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was adopted 33 years after Marshall's death.

Having grown from a Reformed Church academy, Marshall College, named upon the death of Chief Justice John Marshall, officially opened in 1836 with a well-established reputation. After a merger with Franklin College in 1853, the school was renamed Franklin and Marshall College. The college went on to become one of the nation's foremost liberal arts colleges.

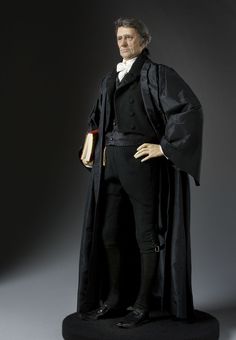

Marshall's home in Richmond, Virginia, has been preserved by Preservation Virginia (formerly known as the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities). It is considered to be an important landmark and museum, essential to an understanding of the Chief Justice's life and work. The United States Bar Association commissioned Sculptor william Wetmore Story to execute the statue of Marshall that now stands inside the Supreme Court on the ground floor. Another casting of the statue is located at Constitution Ave. and 4th Street in Washington D.C. and a third on the grounds of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Story's father Joseph Story had served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court with Marshall. The statue was originally dedicated in 1884.

An engraved portrait of Marshall appears on U.S. paper money on the series 1890 and 1891 treasury notes. These rare notes are in great demand by note Collectors today. Also, in 1914, an engraved portrait of Marshall was used as the central vignette on series 1914 $500 federal reserve notes. These notes are also quite scarce. (William McKinley replaced Marshall on the $500 bill in 1928.) Example of both notes are available for viewing on the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco website. Marshall was also featured on a commemorative silver dollar in 2005.

In the course of his opinion in this case, Marshall began the careful work of determining what the phrase "commerce...among the several states" means in the Constitution. He stressed that one must look at whether the commerce in question has wide-ranging effects, suggesting that commerce which does "affect other states" may be interstate commerce, even if it does not cross state lines. Of course, the steamboats in this case did cross a state line, but Marshall suggested that his opinion had a broader scope than that. Indeed, Marshall's opinion in Gibbons would be cited by the Supreme Court much later when it upheld aspects of the New Deal in cases like Wickard v. Filburn in 1942. But, the opinion in Gibbons can also be read more narrowly. After all, Marshall also wrote:

On September 24, 1955, the United States Postal Service issued the 40¢ Liberty Issue postage stamp honoring Marshall with a 40 cent stamp.

Marshall's forceful personality allowed him to steer his fellow Justices; only once did he find himself on the losing side in a constitutional case. In that case—Ogden v. Saunders in 1827—Marshall set forth his general principles of constitutional interpretation: