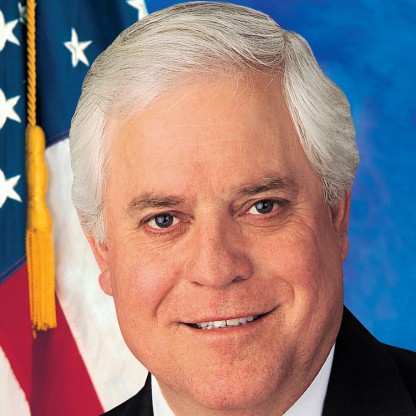

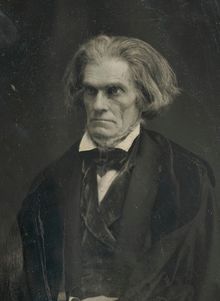

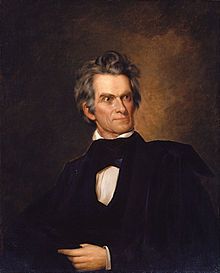

| Who is it? | 7th Vice President of the U.S.A |

| Birth Day | March 18, 1782 |

| Birth Place | Abbeville, United States |

| Age | 237 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | March 31, 1850(1850-03-31) (aged 68)\nWashington, D.C., U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| President | James Monroe |

| Preceded by | Joseph Calhoun |

| Succeeded by | Eldred Simkins |

| Resting place | St. Philip's Church |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (Before 1828) Nullifier (1828–1839) Democratic (1839–1850) |

| Spouse(s) | Floride Bonneau (m. 1811) |

| Children | 10, including Anna Maria Calhoun Clemson |

| Parents | Patrick Calhoun Martha Caldwell |

| Education | Yale University Litchfield Law School |

John C. Calhoun, famous for serving as the 7th Vice President of the United States, is estimated to have a net worth of $850,000 in 2025. Calhoun, known for his influential role in American politics during the early 19th century, accumulated his wealth through various means, including his successful legal career and extensive land holdings. Despite his financial success, Calhoun is primarily remembered for his political accomplishments and contributions to the shaping of his nation.

Calhoun admired Dwight's extemporaneous sermons, his seemingly encyclopedic knowledge, and his awesome mastery of the classics, of the tenets of Calvinism, and of metaphysics. No one, he thought, could explicate the language of John Locke with such clarity.

John Caldwell Calhoun was born in Abbeville District, South Carolina on March 18, 1782, the fourth child of Patrick Calhoun (1727–1796) and his wife Martha Caldwell. Patrick's father, also named Patrick Calhoun, had joined the Scotch-Irish immigration movement from County Donegal to southwestern Pennsylvania. After the death of the elder Patrick in 1741, the family moved to southwestern Virginia. Following the defeat of British General Edward Braddock at the Battle of the Monongahela in 1755, the family, fearing Indian attacks, moved to South Carolina in 1756. Patrick Calhoun belonged to the Calhoun clan in the tight-knit Scotch-Irish community on the Southern frontier. He was known as an Indian fighter and an ambitious surveyor, farmer, planter and Politician, being a member of the South Carolina Legislature. As a Presbyterian, he stood opposed to the Anglican elite based in Charleston. He was a Patriot in the American Revolution, and opposed ratification of the federal Constitution on grounds of states' rights and personal liberties. Calhoun would eventually adopt his father's states' rights beliefs.

Jackson sided with the Eatons. He and his late wife Rachel Donelson had undergone similar political attacks stemming from their marriage in 1791. The two had married in 1791 not knowing that Rachel's first husband, Lewis Robards, had failed to finalize the expected divorce. Once the divorce was finalized, they married legally in 1794, but the episode caused a major controversy, and was used against him in the 1828 campaign. Jackson saw attacks on Eaton stemming ultimately from the political opposition of Calhoun, who had failed to silence his wife's criticisms. The Calhouns were widely regarded as the chief instigators.

Historian Lee H. Cheek, Jr., distinguishes between two strands of American republicanism: the puritan tradition, based in New England, and the agrarian or South Atlantic tradition, which Cheek argues was espoused by Calhoun. While the New England tradition stressed a politically centralized enforcement of moral and religious norms to secure civic virtue, the South Atlantic tradition relied on a decentralized moral and religious order based on the idea of subsidiarity (or localism). Cheek maintains that the "Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions" (1798), written by Jefferson and Madison, were the cornerstone of Calhoun's republicanism. Calhoun emphasized the primacy of subsidiarity——holding that popular rule is best expressed in local communities that are nearly autonomous while serving as units of a larger society.

With financing from his brothers, he went to Yale College in Connecticut in 1802. For the first time in his life, Calhoun encountered serious, advanced, well-organized intellectual dialogue that could shape his mind. Yale was dominated by President Timothy Dwight, a Federalist who became his mentor. Dwight's brilliance entranced (and sometimes repelled) Calhoun. Biographer John Niven says:

Calhoun made friends easily, read widely, and was a noted member of the debating society of Brothers in Unity. He graduated as valedictorian in 1804. He studied law at the nation's only real law school, Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, where he worked with Tapping Reeve and James Gould. He was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1807. Biographer Margaret Coit argues that:

With a base among the Irish and Scotch Irish, Calhoun won election to the House of Representatives in 1810. He immediately became a leader of the War Hawks, along with Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky and South Carolina congressmen william Lowndes and Langdon Cheves. Brushing aside the vehement objections of both anti-war New Englanders and arch-conservative Jeffersonians led by John Randolph of Roanoke, they demanded war against Britain to preserve American honor and republican values, which had been violated by the British refusal to recognize American shipping rights. As a member, and later acting chairman, of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Calhoun played a major role in drafting two key documents in the push for war, the Report on Foreign Relations and the War Report of 1812. Drawing on the linguistic tradition of the Declaration of Independence, Calhoun's committee called for a declaration of war in ringing phrases, denouncing Britain's "lust for power", "unbounded tyranny", and "mad ambition". Historian James Roark says, "These were fighting words in a war that was in large measure about insult and honor." The United States declared war on Britain on June 18, inaugurating the War of 1812. The opening phase involved multiple disasters for American arms, as well as a financial crisis when the Treasury could barely pay the bills. The conflict caused economic hardship for the Americans, as the Royal Navy blockaded the ports and cut off imports, exports and the coastal trade. Several attempted invasions of Canada were fiascos, but the U.S. in 1813 seized control of Lake Erie and broke the power of hostile Indians in battles such as the Battle of the Thames in Canada in 1813 and the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in Alabama in 1814. These Indians had, in many cases, cooperated with the British or Spanish in opposing American interests.

In January 1811, Calhoun married Floride Bonneau Colhoun, a first cousin once removed. She was the daughter of wealthy United States Senator and Lawyer John E. Colhoun, a leader of Charleston high society. The couple had 10 children over 18 years: Andrew Pickens Calhoun, Floride Pure Calhoun, Jane Calhoun, Anna Maria Calhoun, Elizabeth Calhoun, Patrick Calhoun, John Caldwell Calhoun Jr., Martha Cornelia Calhoun, James Edward Calhoun, and william Lowndes Calhoun. Three of them, Floride Pure, Jane, and Elizabeth, died in infancy. Calhoun's fourth child, Anna Maria, married Thomas Green Clemson, founder of Clemson University in South Carolina.

John Niven paints a portrait of Calhoun that is both sympathetic and tragic. He says that Calhoun's ambition and personal desires "were often thwarted by lesser men than he." Niven identifies Calhoun as a "driven man and a tragic figure." He argues that Calhoun was motivated by the near disaster of the War of 1812, of which he was a "thoughtless advocate," to work towards fighting for the freedoms and securities of the white Southern people against any kind of threat. Ultimately, Niven says, he "... would overcompensate and in the end would more than any other individual destroy the culture he sought to preserve, perpetuating for several generations the very insecurity that had shaped his public career."

Calhoun labored to raise troops, provide funds, speed Logistics, rescue the currency, and regulate commerce to aid the war effort. One colleague hailed him as "the young Hercules who carried the war on his shoulders." Disasters on the battlefield made him double his legislative efforts to overcome the obstructionism of John Randolph, Daniel Webster, and other opponents of the war. In December 1814, with the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte apparently defeated, and the British invasions of New York and Baltimore thwarted, British and American diplomats signed the Treaty of Ghent. It called for a return to the borders of 1812 with no gains or losses. Before the treaty reached the Senate for ratification, and even before news of its signing reached New Orleans, a massive British invasion force was utterly defeated in January 1815 at the Battle of New Orleans, making a national hero of General Andrew Jackson. Americans celebrated what they called a "second war of independence" against Britain. This led to the beginning of the "Era of Good Feelings", an era marked by the formal demise of the Federalist Party and increased nationalism.

Despite American successes, the mismanagement of the Army during the war distressed Calhoun, and he resolved to strengthen and centralize the War Department. The militia had proven itself quite unreliable during the war and Calhoun saw the need for a permanent and professional military force. In 1816 he called for building an effective navy, including steam frigates, as well as a standing army of adequate size. The British blockade of the coast had underscored the necessity of rapid means of internal transportation; Calhoun proposed a system of "great permanent roads". The blockade had cut off the import of manufactured items, so he emphasized the need to encourage more domestic manufacture, fully realizing that industry was based in the Northeast. The dependence of the old financial system on import duties was devastated when the blockade cut off imports. Calhoun called for a system of internal taxation that would not collapse from a war-time shrinkage of maritime trade, as the tariffs had done. The expiration of the charter of the First Bank of the United States had also distressed the Treasury, so to reinvigorate and modernize the economy Calhoun called for a new national bank. A new bank was chartered as the Second Bank of the United States by Congress and approved by President James Madison in 1816. Through his proposals, Calhoun emphasized a national footing and downplayed sectionalism and states rights. Historian Ulrich B. Phillips says that at this stage of Calhoun's career, "The word nation was often on his lips, and his conviction was to enhance national unity which he identified with national power."

In 1817, the deplorable state of the War Department led four men to decline offers from President James Monroe to accept the office of Secretary of War before Calhoun finally assumed the role. Calhoun took office on December 8 and served until 1825. He continued his role as a leading nationalist during the Era of Good Feelings. He proposed an elaborate program of national reforms to the infrastructure that he believed would speed economic modernization. His first priority was an effective navy, including steam frigates, and in the second place a standing army of adequate size—and as further preparation for emergency, "great permanent roads", "a certain encouragement" to manufactures, and a system of internal taxation that would not collapse from a war-time shrinkage of maritime trade, like customs duties.

After the war ended in 1815 the "Old Republicans" in Congress, with their Jeffersonian ideology for economy in the federal government, sought to reduce the operations and finances of the War Department. Calhoun's political rivalry with william H. Crawford, the Secretary of the Treasury, over the pursuit of the presidency in the 1824 election complicated Calhoun's tenure as War Secretary. The general lack of military action following the war meant that a large army, such as that preferred by Calhoun, was no longer considered necessary. The "Radicals", a group of strong states' rights supporters who mostly favored Crawford for President in the coming election, were inherently suspicious of large armies. Some allegedly also wanted to hinder Calhoun's own presidential aspirations for that election. Thus, on March 2, 1821, Congress passed the Reduction Act, which reduced the number of enlisted men of the army by half, from 11,709 to 5,586, and the number of the officer corps by a fifth, from 680 to 540. Calhoun, though concerned, offered little protest. Later, to provide the army with a more organized command structure, which had been severely lacking during the War of 1812, he appointed Major General Jacob Brown to a position that would later become known as "Commanding General of the United States Army".

Calhoun was initially a candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1824. Four other men also sought the presidency: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, william H. Crawford, and Henry Clay. Calhoun failed to win the endorsement of the South Carolina legislature, and his supporters in Pennsylvania decided to abandon his candidacy in favor of Jackson's, and instead supported him for vice President. Other states soon followed, and Calhoun therefore allowed himself to become a candidate for vice President rather than President. The Electoral College elected Calhoun vice President by a landslide. He won 182 votes out of 261 electoral votes, while five other men received the remaining votes. No presidential candidate received a majority in the Electoral College, and the election was ultimately resolved by the House of Representatives, where Adams was declared the winner over Crawford and Jackson, who in the election had led Adams in both popular vote and electoral vote. After Clay, the Speaker of the House, was appointed Secretary of State by Adams, Jackson's supporters denounced what they considered a "corrupt bargain" between Adams and Clay to give Adams the presidency in exchange for Clay receiving the office of Secretary of State, the holder of which had traditionally become the next President. Calhoun also expressed some concerns, which caused friction between him and Adams.

As secretary, Calhoun had responsibility for management of Indian affairs. He promoted a plan, adopted by Monroe in 1825, to preserve the sovereignty of eastern Indians by relocating them to western reservations they could control without interference from state governments. In over seven years Calhoun supervised the negotiation and ratification of 40 treaties with Indian tribes. Calhoun opposed the invasion of Florida launched in 1818 by General Jackson during the First Seminole War, which was done without direct authorization from Calhoun or President Monroe. The United States annexed Florida from Spain in 1819 through the Adams–Onís Treaty. A reform-minded modernizer, he attempted to institute centralization and efficiency in the Indian Department and in the Army by establishing new coastal and frontier fortifications and building military roads, but Congress either failed to respond to his reforms or responded with hostility. Calhoun's frustration with congressional inaction, political rivalries, and ideological differences spurred him to create the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1824. The responsibilities of the bureau were to manage treaty negotiations, schools, and trade with Indians, in addition to handling all expenditures and correspondence concerning Indian affairs. Thomas McKenney was appointed as the first head of the bureau.

Calhoun also opposed President Adams' plan to send a delegation to observe a meeting of South and Central American Leaders in Panama, believing that the United States should stay out of foreign affairs. Calhoun became disillusioned with Adams' high tariff policies and increased centralization of government through a network of "internal improvements", which he now saw as a threat to the rights of the states. Calhoun wrote to Jackson on June 4, 1826, informing him that he would support Jackson's second campaign for the presidency in 1828. The two were never particularly close friends. Calhoun never fully trusted Jackson, a frontiersman and popular war hero, but hoped that his election would bring some reprieve from Adams's anti-states' rights policies. Jackson selected Calhoun as his running mate, and together they defeated Adams and his running mate Richard Rush. Calhoun thus became the second of two vice Presidents to serve under two different Presidents. The only other man who accomplished this feat was George Clinton, who served as Vice President from 1805 to 1812 under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

Calhoun had begun to oppose increases in protective tariffs, as they generally benefitted Northerners more than Southerners. While he was Vice President in the Adams administration, Jackson's supporters devised a high tariff legislation that placed duties on imports that were also made in New England. Calhoun had been assured that the northeastern interests would reject the Tariff of 1828, exposing pro-Adams New England congressmen to charges that they selfishly opposed legislation popular among Jacksonian Democrats in the west and Mid-Atlantic States. The southern legislators miscalculated and the so-called "Tariff of Abominations" passed and was signed into law by President Adams. Frustrated, Calhoun returned to his South Carolina plantation, where he anonymously composed "South Carolina Exposition and Protest," an essay rejecting the centralization philosophy and supporting the principle of nullification as a means to prevent tyranny of a central government.

In "South Carolina Exposition and Protest", Calhoun argued that a state could veto any federal law that went beyond the enumerated powers and encroached upon the residual powers of the State. President Jackson, meanwhile, generally supported states' rights, but opposed nullification and secession. At the 1830 Jefferson Day dinner at Jesse Brown's Indian Queen Hotel, Jackson proposed a toast and proclaimed, "Our federal Union, it must be preserved." Calhoun replied, "The Union, next to our liberty, the most dear. May we all remember that it can only be preserved by respecting the rights of the states, and distributing equally the benefit and burden of the Union." Calhoun's publication of letters from the Seminole in the Telegraph caused his relationship with Jackson to deteriorate further, thus contributing to the Nullification crisis. Jackson and Calhoun began an angry correspondence that lasted until Jackson stopped it in July.

Finally in the spring of 1831, at the suggestion of Secretary of State Martin Van Buren, who, like Jackson, supported the Eatons, Jackson replaced all but one of his Cabinet members, thereby limiting Calhoun's influence. Van Buren began the process by resigning as Secretary of State, facilitating Jackson's removal of others. Van Buren thereby grew in favor with Jackson, while the rift between the President and Calhoun was widened. Later, in 1832, Calhoun, as vice President, cast a tie-breaking vote against Jackson's nomination of Van Buren as Minister to Great Britain in a failed attempt to end Van Buren's political career. Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, a staunch supporter of Jackson, then stated that Calhoun had "elected a Vice President", as Van Buren was able to move past his failed nomination as Minister to Great Britain and instead gain the Democratic Party's vice presidential nomination in the 1832 election, in which he and Jackson were victorious.

When Calhoun took his seat in the Senate on December 29, 1832, his chances of becoming President were considered poor due to his involvement in the Nullification Crisis, which left him without connections to a major national party. After implementation of the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which helped solve the Nullification Crisis, the Nullifier Party, along with other anti-Jackson politicians, formed a coalition known as the Whig Party. Calhoun sometimes affiliated with the Whigs, but chose to remain a virtual independent due to the Whig promotion of federally subsidized "internal improvements."

From 1833 to 1834, Jackson was engaged in removing federal funds from the Second Bank of the United States during the Bank War. Calhoun opposed this action, considering it a dangerous expansion of executive power. He called the men of the Jackson administration "artful, cunning, and corrupt politicians, and not fearless warriors." He accused Jackson of being ignorant on financial matters. As evidence, he cited the economic panic caused by Nicholas Biddle as a means to stop Jackson from destroying the Bank. On March 28, 1834, Calhoun voted with the Whig senators on a successful motion to censure Jackson for his removal of the funds. In 1837, he refused to attend the inauguration of Jackson's chosen successor, Van Buren, even as other powerful senators who opposed the administration such as Webster and Clay did witness the inauguration. However, by 1837 Calhoun generally had realigned himself with most of the Democrats' policies.

Whereas other Southern politicians had excused slavery as a "necessary evil," in a famous speech on the Senate floor on February 6, 1837, Calhoun asserted that slavery was a "positive good." He rooted this claim on two grounds: white supremacy and paternalism. All societies, Calhoun claimed, are ruled by an elite group that enjoys the fruits of the labor of a less-exceptional group. Senator william Cabell Rives of Virginia earlier had referred to slavery as an evil that might become a "lesser evil" in some circumstances. Calhoun believed that conceded too much to the abolitionists:

In the 1840s three interpretations of the constitutional powers of Congress to deal with slavery in territories emerged: the "free-soil doctrine," the "popular sovereignty position," and the "Calhoun doctrine." The Free Soilers stated that Congress had the power to outlaw slavery in the territories. The popular sovereignty position argued that the voters living there should decide. The Calhoun doctrine said that Congress and the citizens of the territories could never outlaw slavery in the territories.

Tyler and his allies had, since 1843, devised and encouraged national propaganda promoting Texas annexation, which understated Southern slaveholder's aspirations regarding the Future of Texas. Instead, Tyler chose to portray the annexation of Texas as something that would prove economically beneficial to the nation as a whole. The further introduction of slavery into the vast expanses of Texas and beyond, they argued, would "diffuse" rather than concentrate slavery regionally, ultimately weakening white attachment and dependence on slave labor. This theory was yoked to the growing enthusiasm among Americans for Manifest Destiny, a Desire to see the social, economic and moral precepts of republicanism spread across the continent. Moreover, Tyler declared that national security was at stake: If foreign powers – Great Britain in particular – were to gain influence in Texas, it would be reduced to a British cotton-producing reserve and a base to exert geostrategic influence over North America. Texas might be coerced into relinquishing slavery, inducing slave uprisings in adjoining slave states and deepening sectional conflicts between American free-soil and slave-soil interests. The appointment of Calhoun, with his southern states' rights reputation – which some believed was "synonymous with slavery" – threatened to cast doubt on Tyler's carefully crafted reputation as a nationalist. Tyler, though ambivalent, felt obliged to enlist Calhoun as Secretary of State, because Tyler's closest confidantes had, in haste, offered the position to the South Carolinian statesman in the immediate aftermath of the Princeton disaster. Calhoun would be confirmed by Congress by unanimous vote.

At the Democratic Convention in Baltimore, Maryland in May 1844, Calhoun's supporters, with Calhoun in attendance, threatened to bolt the proceedings and shift support to Tyler's third party ticket if the delegates failed to produce a pro-Texas nominee. Calhoun's Pakenham letter, and its identification with proslavery extremism, moved the presumptive Democratic Party nominee, the northerner Martin Van Buren, into denouncing annexation. Therefore, Van Buren, already not widely popular in the South, saw his support from that region crippled. As a result, James K. Polk, a pro-Texas Jacksonian and Tennessee Politician, won the nomination. Daniel Howe claims that Calhoun's Pakenham letter was a deliberate attempt to influence the outcome of the 1844 election, writing:

Calhoun was reelected to the Senate in 1845 following the resignation of Daniel Elliott Huger. He soon became vocally opposed to the Mexican–American War. He believed that it would distort the national character by undermining republicanism in favor of empire and by bringing non-white persons into the country. (See § The evils of war and political parties.) When Congress declared war against Mexico on May 13, he abstained from voting on the measure. Calhoun also vigorously opposed the Wilmot Proviso, an 1846 proposal by Pennsylvania Representative David Wilmot to ban slavery in all newly acquired territories. The House of Representatives, through its Northern majority, passed the provision several times. However, the Senate, where non-slave and slave states had more equal representation, never passed the measure.

A major crisis emerged from the persistent Oregon boundary dispute between Great Britain and the United States, due to an increasing number of American migrants. The territory included most of present-day British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. American expansionists used the slogan "54–40 or fight" in reference to the Northern boundary coordinates of the Oregon territory. The parties compromised, ending the war threat, by splitting the area down the middle at the 49th parallel, with the British acquiring British Columbia and the Americans accepting Washington and Oregon. Calhoun, along with President Polk and Secretary of State James Buchanan, continued work on the treaty while he was a senator, and it was ratified by a vote of 41–14 on June 18, 1846.

Anti-slavery Northerners denounced the war as a Southern conspiracy to expand slavery; Calhoun in turn perceived a connivance of Yankees to destroy the South. By 1847 he decided the Union was threatened by a totally corrupt party system. He believed that in their lust for office, patronage and spoils, politicians in the North pandered to the anti-slavery vote, especially during presidential campaigns, and politicians in the slave states sacrificed Southern rights in an effort to placate the Northern wings of their parties. Thus, the essential first step in any successful assertion of Southern rights had to be the jettisoning of all party ties. In 1848–49, Calhoun tried to give substance to his call for Southern unity. He was the driving force behind the drafting and publication of the "Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress, to Their Constituents." It alleged Northern violations of the constitutional rights of the South, then warned Southern voters to expect forced emancipation of slaves in the near Future, followed by their complete subjugation by an unholy alliance of unprincipled Northerners and blacks. Whites would flee and the South would "become the permanent abode of disorder, anarchy, poverty, misery, and wretchedness." Only the immediate and unflinching unity of Southern whites could prevent such a disaster. Such unity would either bring the North to its senses or lay the foundation for an independent South. But the spirit of union was still strong in the region and fewer than 40% of the Southern congressmen signed the address, and only one Whig.

Calhoun was consistently opposed to the War with Mexico, arguing that an enlarged military effort would only feed the alarming and growing lust of the public for empire regardless of its constitutional dangers, bloat executive powers and patronage, and saddle the republic with a soaring debt that would disrupt finances and encourage speculation. Calhoun feared, moreover, that Southern slave owners would be shut out of any conquered Mexican territories, as nearly happened with the Wilmot Proviso. He argued that the war would detrimentally lead to the annexation of all of Mexico, which would bring Mexicans into the country, whom he considered deficient in moral and intellectual terms. He said, in a speech on January 4, 1848:

Calhoun's ideas on the concurrent majority are illustrated in A Disquisition on Government. The Disquisition is a 100-page essay on Calhoun's definitive and comprehensive ideas on government, which he worked on intermittently for six years until its 1849 completion. It systematically presents his arguments that a numerical majority in any government will typically impose a despotism over a minority unless some way is devised to secure the assent of all classes, sections, and interests and, similarly, that innate human depravity would debase government in a democracy.

Shortly after delivering his speech against the Compromise of 1850, Calhoun predicted the destruction of the Union over the slavery issue. Speaking to Senator Mason, he said:

In what Historian Robert R. Russell calls the "Calhoun Doctrine," Calhoun argued that the Federal Government's role in the territories was only that of the trustee or agent of the several sovereign states: it was obliged not to discriminate among the states and hence was incapable of forbidding the bringing into any territory of anything that was legal property in any state. Calhoun argued that citizens from every state had the right to take their property to any territory. Congress and local voters, he asserted, had no authority to place restrictions on slavery in the territories. As constitutional Historian Hermann von Holst noted, "Calhoun's doctrine made it a solemn constitutional duty of the United States government and of the American people to act as if the existence or non-existence of slavery in the Territories did not concern them in the least." The Calhoun Doctrine was opposed by the Free Soil forces, which merged into the new Republican Party around 1854. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney based his decision in the 1857 Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which he ruled that the federal government could not prohibit slavery in any of the territories, upon Calhoun's arguments. However, moderates at this time rejected these beliefs, and Taney's decision became a major point of partisan attack by the Republican Party.

Calhoun was despised by Jackson and his supporters for his alleged attempts to subvert the unity of the nation for his own political gain. On his deathbed, Jackson regretted that he had not had Calhoun executed for treason. "My country," he declared, "would have sustained me in the act, and his fate would have been a warning to traitors in all time to come." Even after his death, Calhoun's reputation among Jacksonians remained poor. They disparaged him by portraying him as a man thirsty for power, who when he failed to attain it, sought to tear down his country with him. According to Parton, writing in 1860:

Calhoun's widow, Floride, died on July 25, 1866, and was buried in St. Paul's Episcopal Church Cemetery in Pendleton, South Carolina, near their children, but apart from her husband.

Many different places, streets and schools were named after Calhoun, as may be seen on the above list. The "Immortal Trio" were memorialized with streets in Uptown New Orleans. Calhoun Landing, on the Santee-Cooper River in Santee, South Carolina, was named after him. In 1887, a monument to Calhoun was erected in Marion Square, Charleston; it was not well-liked by the residents and was replaced in 1896 by a different monument that still stands. The USS John C. Calhoun, in commission from 1963 to 1994, was a Fleet Ballistic Missile nuclear submarine.

Historian Richard Hofstadter (1948) emphasizes that Calhoun's conception of minority was very different from the minorities of a century later:

Calhoun is often remembered for his defense of minority rights, in the context of defending white Southern interests from perceived Northern threats, by use of the "concurrent majority." He is also noted and criticized for his strong defense of slavery. These positions played an enormous role in influencing Southern secessionist Leaders by strengthening the trend of sectionalism, thus contributing to the Civil War. During his lifetime and after, Calhoun was seen as one of the Senate's most important figures. In 1957, a Senate committee chaired by John F. Kennedy selected Calhoun as one of the five greatest United States senators in history. Biographer Irving Bartlett wrote:

Biographer John Niven argues "that these moves were part of a well-thought-out plan whereby Hayne would restrain the hotheads in the state legislature and Calhoun would defend his brainchild, nullification, in Washington against administration stalwarts and the likes of Daniel Webster, the new apostle of northern nationalism." Calhoun was the first of two vice Presidents to resign, the second being Spiro Agnew in 1973. During his terms as vice President, he made a record of 31 tie-breaking votes in Congress.

Calhoun was portrayed by actor Arliss Howard in the 1997 film Amistad. The film depicts the controversy and legal battle surrounding the status of slaves who in 1839 rebelled against their transporters on La Amistad slave ship.

Dwight repeatedly denounced Jeffersonian democracy, and Calhoun challenged him in class. Dwight could not shake Calhoun's commitment to republicanism. "Young man," retorted Dwight, "your talents are of a high order and might justify you for any station, but I deeply regret that you do not love sound principles better than sophistry – you seem to possess a most unfortunate bias for error." Dwight also expounded on the strategy of secession from the Union as a legitimate solution for New England's disagreements with the national government.

Calhoun's basic concern for protecting the diversity of minority interests is expressed in his chief contribution to political science—the idea of a concurrent majority across different groups as distinguished from a numerical majority. A concurrent majority is a system in which a minority group is permitted to exercise a sort of veto power over actions of a majority that are believed to infringe upon the minority's rights.

Recently, Calhoun's reputation has suffered particularly due to his defense of slavery. The racially motivated Charleston church shooting in South Carolina in June 2015 reinvigorated demands for the removal of monuments dedicated to prominent pro-slavery and Confederate States figures. That month, the monument to Calhoun in Charleston was found vandalized, with spray-painted denunciations of Calhoun as a racist and a defender of slavery.

In response to decades of requests, Yale President Peter Salovey announced that the university's Calhoun College will be renamed in 2017 to honor Grace Murray Hopper, a pioneering computer programmer, Mathematician and Navy rear admiral who graduated from Yale. Calhoun is commemorated elsewhere on the campus, including the exterior of Harkness Tower, a prominent campus landmark, as one of Yale's "Eight Worthies."