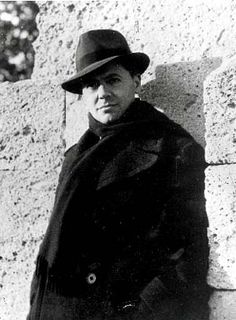

| Who is it? | An Emblem of the Resistance |

| Birth Day | June 18, 20 |

| Birth Place | Béziers, French |

| Died On | July 8, 1943 |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

Jean Moulin, the renowned emblem of the French Resistance, is anticipated to have a net worth of $13 million by 2025. Jean Moulin has been an iconic figure in French history due to his unwavering dedication to the Resistance during World War II. His influential role in unifying different factions of the Resistance and organizing resistance cells has earned him immense respect. Apart from his courageous efforts, Jean Moulin's legacy lives on as an inspiration for liberty and resistance against oppression. Though financial figures cannot truly represent his significance, his estimated net worth serves as a testament to his lasting impact on French society.

Jean Pierre Moulin was born at 6 rue d'Alsace in Béziers (Hérault), son of Antoine-Émile Moulin and Blanche Élisabeth Pègue. He is the grandson of an insurgent of 1851. Antoine-Émile Moulin is a lay Teacher at the Université Populaire, and Freemason at the lodge Action sociale. He was baptized on August 6, 1899 by Father Guigues in the Saint-Vincent church of Saint-Andiol (Bouches-du-Rhône), the original village of his parents: his godfather is his brother Joseph Moulin and his godmother is his cousin Jeanne Sabatier. He spent an uneventful childhood in the company of his sister Laure and his brother Joseph (who died of pneumonia in 1907). In high school Henri IV of Beziers, he is an average student.

Later, and in the tradition of his father, elected general counsel of the Herault in 1913 under the radical-socialist banner.

In 1917, he enrolled at the Faculty of Law of Montpellier, where he is not a brilliant student, but thanks to the interpersonal skills of his father, he was appointed attaché to the cabinet of the prefect of Herault under the presidency of Raymond Poincaré.

Mobilized April 17, 1918, Jean Moulin is assigned to the 2nd Regiment of Engineering (based in Metz after the victory). After an accelerated training, he arrived in the Vosges at Charmes on September 20th and was preparing to go online when the armistice was proclaimed. He was sent successively to Seine-et-Oise, to Verdun, then to Chalon-sur-Saone; he works as a carpenter, a digger and later a telephonist for the 7th and 9th Engineer Regiments. He was then demobilized and he resumed his duties at the Prefecture of Montpellier on 4 November 1919.

After World War I, he resumed his studies and obtained a law degree in 1921. Moulin then entered the prefectural administration as chef de cabinet to the deputy of Savoie in 1922, then as sous-préfet of Albertville, from 1925 to 1930.

After being rejected by Jeanette Auran, Moulin, aged 27, married professional singer, Marguerite Cerruti, 19, in the town of Betton-Bettonet in September 1926. Cerruti quickly became bored with the marriage and Moulin responded by offering her further singing lessons in Paris whereupon she disappeared for 2 days Biographer Patrick Marnham cites one of the causes of the divorce being Moulin's mother-in-law, who had by then, wanted to prevent her estate passing to Moulin's control upon Cerruti's 21 birthday. Moulin attempted to hide his rejection by the bourgeoisie by excusing his wife's disappearances and only informing his family after the divorce.

Moulin was appointed sous-préfet of Châteaulin, Brittany in 1930, when he drew political cartoons for the newspaper Le Rire on the side under the pseudonym Romanin. He also illustrated books by the Breton poet Tristan Corbière, including an etching for La Pastorale de Conlie, Corbière's poem about Camp Conlie where many Breton Soldiers died in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. He also made friends with the Breton poets Saint-Pol-Roux in Camaret and Max Jacob in Quimper.

In 1932, Pierre Cot, a Radical Socialist Politician, named Moulin his chef adjoint when he was serving as Foreign Minister under Paul Doumer's presidency. In 1933, Moulin was appointed sous-préfet of Thonon-les-Bains, parallel to his function of head of cabinet of Pierre Cot in the Air ministry under Albert Lebrun. On 19 January 1934, Moulin was appointed sous-préfet of Montargis, but he did not assume this office and chose to remain under Pierre Cot. In the first half of April Moulin was appointed to the Seine préfecture, and, 1 July, took his place as secretary general in Somme, in Amiens. In 1936 he was once more named chief of cabinet of Pierre Cot's Air ministry of the Popular Front. In this capacity, Moulin was involved in Cot's efforts to assist the Spanish Republic by sending them planes and pilots. For the Istres-Damas-Le Bourget race he presented the winners with their prize; Benito Mussolini's son was one of those winners. He became France's youngest préfet in the Aveyron département, based in the commune of Rodez, in January 1937. It has been claimed that during the Spanish Civil War Moulin assisted with the shipment of arms from the Soviet Union to Spain. A more commonly accepted version of events is that he used his position in the French aviation ministry to deliver planes to the Spanish Republican forces.

On 3 November 1940, the Vichy government ordered all préfets to dismiss left-wing elected mayors of towns and villages. When Moulin refused, he was himself removed from office on 16 November 1940.

He then went to live in Saint-Andiol (Bouches-du-Rhône), and joined the French Resistance. He reached London in September 1941 under the name Joseph Jean Mercier, and met General Charles de Gaulle on 24 October, who gave him the assignment of unifying the various Resistance groups. On 1 January 1942, he parachuted into the Alpilles and met with the Leaders of the resistance groups under code names Rex and Max:

It has also been suggested, principally in Marnham's biography, that Moulin was betrayed by communists. Marnham points the finger specifically at Raymond Aubrac and possibly his wife, Lucie. He alleges that communists did at times betray non-communists to the Gestapo, and that Aubrac was linked to harsh actions during the purge of collaborators after the war. In 1990, Klaus Barbie, by then "a bitter dying Nazi", named Aubrac as the traitor. To counteract the accusations levelled at Moulin, Daniel Cordier, his personal secretary during the war, wrote a biography of his former leader. In April 1997, Vergès produced a "Barbie testament" which he claimed that Barbie had given him ten years earlier which purported to show the Aubracs had tipped off Barbie. Vergès's "Barbie testament" which was timed for the publication of the book Aubrac Lyon 1943 by Gérard Chauvy, which was meant to prove that the Aubracs were the ones who informed Barbie about the fateful meeting at Caluire on 21 June 1943. On 2 April 1998 following a civil suit launched by the Aubracs, a Paris court fined Chauvy and his publisher Albin Michel for "public defamation". In 1998, the French Historian Jacques Baynac in his book Les Secrets de l'affaire Jean Moulin claimed that Moulin was planning to break with de Gaulle to recognize General Giraud, which led the Gaullists to tip off Barbie before this could happen.

The British intelligence officer Peter Wright in his 1987 book Spy Catcher wrote that Pierre Cot was an "active Russian agent" and called his protege Moulin a "dedicated Communist". Clinton wrote that Wright based his allegations against Moulin entirely on secret documents that he claimed to have seen, which no Historian has ever seen, and on conversations that he is supposed to have had decades ago with others long dead, which made his case against Moulin very "dubious". Henri-Christian Giraud, the grandson of General Henri Giraud who had been outmaneuvered by de Gaulle for the leadership of the Free French movement hit back in his two volume work De Gaulle et les communistes published in 1988 and 1989 which outlined a conspiracy theory suggesting that de Gaulle had been "manipulated" by the "Soviet agent" Moulin into the following the PCF's line of "national insurrection" and thereby eclipsed his grandfather, who he maintained should have been the rightful leader of Free France. Taking up Giraud's theories, the Lawyer Charles Benfredj argued in his 1990 book L'Affaire Jean Moulin: Le contre-enquête that Moulin was a Soviet agent who had been not killed by Barbie, but had allowed by the German government to go to the Soviet Union in 1943, where Moulin supposedly died sometime after the war. Benfredj's book was published with an introduction with Jacques Soustelle, the archaeologist of Mexico and wartime Gaullist whose commitment to Algérie française had made him a bitter enemy of de Gaulle by 1959. The essence of all the theories about Moulin the alleged Soviet agent was that because de Gaulle had agreed to co-operate with the Communists during WW II (which was apparently all Moulin's work), that this had set France on the wrong course and led to de Gaulle granting Algeria independence in 1962, instead of keeping Algeria as a part of France as he should have done.

Jean Moulin's private life has been a subject of debate, and he has been called a gay apostle. In 2003, the 'Dictionary of Gay and Lesbian Cultures', supervised by Didier Eribon, evokes "the possible homosexuality or bisexuality of a great resistance member, like Jean Moulin", also pointing out the predispositions of homosexuals of the time to enter the resistance, emanating from clandestine activity in their private life. Jean-Paul Sartre, in a 1949 article recalled the predispositions of Parisian homosexual circles to collaboration. In 'Jean Moulin, the ultimate mystery', Pierre Péan and Laurent Ducastel dedicate a chapter on this subject, "Was it?", evoking "a seducer, tasting carnal pleasures with girls, possibly with boys, noting that the official voices of the Liberation will always try to deny the presence of homosexuals in the Resistance, an image that was long not very consistent with the idea of French heroes". Both a friend of Jean Moulin, the poet Max Jacob, were confirmed homosexuals while his secretary, Daniel Cordier, a homosexual 20 years his junior, interviewed for the book of Pierre Péan, claims not to have read the chapter devoted to his sexuality, contenting himself with saying that "he was a ladies' man". The Jean-Moulin museum contains a text saying that Moulin was "a ladies' man, seducer with that - a real 'ladykiller'", while the Historian Thomas Rabino, in 'The other Jean Moulin (2013)' can provide only three female relationships during his life, including one with Marguerite Cerruti, his 'bored' wife who deserted him between 1927 and 1928. In 2013, a remembrance ceremony in France attended by the prime minister was disturbed by anti-gay protestors and a piece of theatre 'The Evangelical Jean Moulin' again discusses this point.

After interrogation, Moulin attempted suicide by cutting his throat with a piece of broken glass. This left him with a scar he would often hide with a scarf—the image of Jean Moulin remembered today. He was discovered by a guard and taken to hospital for treatment.

The current French education curriculum commemorates Jean Moulin as a symbol of the French resistance and a model of civic virtuousness, moral rectitude and patriotism. As of 2015, Jean Moulin was the fifth most popular name for a French school and as of 2016, and his is the 3rd most popular French street name of which 98 percent are male. Lyon 3 university and a Paris metro station have also been named after him. Another member of the resistance, Antoinette Sasse bequeathed her will to found The Musée Jean Moulin in 1994.