| Who is it? | Surgeon |

| Birth Day | April 11, 1755 |

| Birth Place | Shoreditch, British |

| Age | 264 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 21 December 1824(1824-12-21) (aged 69)\nShoreditch, London, England |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Resting place | St Leonard's Church, Shoreditch |

| Residence | 1 Hoxton Square, Shoreditch |

| Alma mater | The London Hospital |

| Occupation | Surgeon |

| Known for | First description of Parkinson's disease |

| Notable work | The Shaking Palsy, 1817 |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Dale |

| Children | 8 |

| Parents | John Parkinson (father) Mary (mother) |

According to current estimates, James Parkinson's net worth is projected to be approximately $1.4 million by 2025. James Parkinson is renowned for his contributions as a British surgeon. He gained considerable recognition for his pioneering work in the medical field, particularly for describing a neurological disorder that would later be named after him, Parkinson's disease. Despite his remarkable achievements in the scientific community, James Parkinson's financial success stems primarily from his medical practice and various investments, leading to a substantial net worth.

On 21 May 1783, he married Mary Dale, with whom he subsequently had eight children; two did not survive past childhood. Soon after he was married, Parkinson succeeded his Father in his practice in 1 Hoxton Square. He believed that any worthwhile surgeon should know shorthand, at which he was adept.

James Parkinson was born in Shoreditch, London, England. He was the son of John Parkinson, an apothecary and surgeon practising in Hoxton Square in London. He was the oldest of five siblings, who included his brother william and his sister Mary Sedgwick. In 1784 Parkinson was approved by the City of London Corporation as a surgeon.

Parkinson called for representation of the people in the House of Commons, the institution of annual parliaments, and universal suffrage. He was a member of several secret political societies, including the London Corresponding Society and the Society for Constitutional Information. In 1794 his membership in the organisation led to his being examined under oath before william Pitt and the Privy Council to give evidence about a trumped-up plot to assassinate King George III. He refused to testify regarding his part in the Popgun Plot, until he was certain he would not be forced to incriminate himself. The plan was to use a poisoned dart fired from a pop-gun to bring the king's reign to a premature conclusion. No charges were ever brought against Parkinson but several of his friends languished in prison for many months before being acquitted.

Parkinson turned away from his tumultuous political career, and between 1799 and 1807 published several medical works, including a work on gout in 1805. He was also responsible for early writings on ruptured appendix.

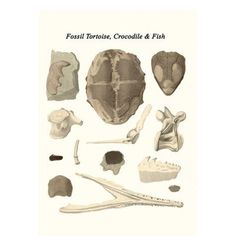

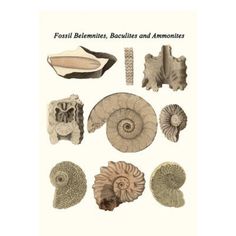

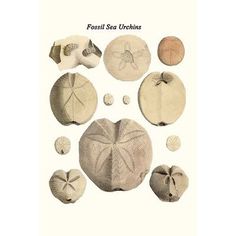

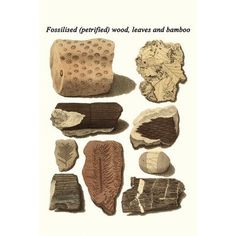

In 1804, the first volume of his Organic Remains of a Former World was published. Gideon Mantell praised it as "the first attempt to give a familiar and scientific account of fossils". A second volume was published in 1808, and a third in 1811. Parkinson illustrated each volume and his daughter Emma coloured some of the plates. The plates were later re-used by Gideon Mantell. In 1822 Parkinson published the shorter "Outlines of Oryctology: an Introduction to the Study of Fossil Organic Remains, especially of those found in British Strata".

Parkinson also contributed several papers to william Nicholson's "A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts", and in the first, second, and fifth volumes of the "Geological Society's Transactions". He wrote a single volume 'Outlines of Oryctology' in 1822, a more popular work. On 13 November 1807, Parkinson and other distinguished gentlemen met at the Freemasons' Tavern in London. The gathering included such great names as Sir Humphry Davy, Arthur Aikin and George Bellas Greenough. This was to be the first meeting of the Geological Society of London.

In 1812 Parkinson assisted his son with the first described case of appendicitis in English, and the first instance in which perforation was shown to be the cause of death.

He died on 21 December 1824 after a stroke that interfered with his speech, bequeathing his houses in Langthorne to his sons and wife and his apothecary's shop to his son, John. His collection of organic remains was given to his wife and much of it went on to be sold in 1827, a catalogue of the sale has never been found. He was buried at St. Leonard's Church, Shoreditch.