| Who is it? | Painter |

| Birth Day | July 10, 1834 |

| Birth Place | Lowell, United States |

| Age | 185 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | July 17, 1903(1903-07-17) (aged 69)\nLondon, England |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Education | United States Military Academy, West Point, New York |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Whistler's Mother |

| Movement | Founder of Tonalism |

| Awards | 1884, elected honorary member, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Munich, Bavaria, Germany 1892, made an officer of the Légion d'honneur, France 1898, charter member and first president of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers |

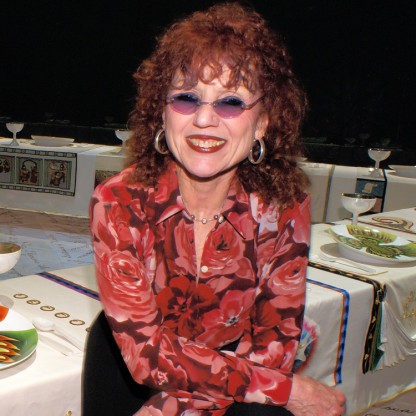

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, a renowned American painter, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in 2025. Highly regarded for his contributions to the art world, Whistler's unique style and innovative techniques have captivated audiences for generations. Known for his influential work, including the famous painting "Whistler's Mother," Whistler's artistic talent has not only earned him critical acclaim but also substantial financial success. As one of the most celebrated painters in the United States, James Abbott McNeill Whistler has solidified his position as an icon in the art industry.

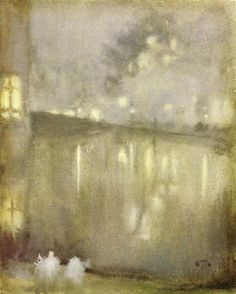

I say I can't thank you too much for the name 'Nocturne' as a title for my moonlights! You have no idea what an irritation it proves to the critics and consequent pleasure to me—besides it is really so charming and does so poetically say all that I want to say and no more than I wish!

James Abbott Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, on July 10, 1834, the first child of Anna Matilda McNeill and George Washington Whistler, and the brother of Confederate surgeon Dr. william McNeill Whistler. His father was a railroad Engineer, and Anna was his second wife. James lived the first three years of his life in a modest house at 243 Worthen Street in Lowell. Today, the house is a museum dedicated to Whistler. During the Ruskin trial (see below), Whistler claimed St. Petersburg, Russia, as his birthplace, declaring, "I shall be born when and where I want, and I do not choose to be born in Lowell."

In 1837, the Whistlers moved from Lowell to Stonington, Connecticut, where George Whistler worked for the Stonington Railroad. Sadly, during this period, three of George and Anna Whistlers' children died in infancy.

In 1839, the Whistlers' fortunes improved considerably when George Whistler received the appointment that would make his fortune and fame - that of chief Engineer for the Boston & Albany Railroad. Thus, the family moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, then one of the United States' most prosperous cities, where they constructed a mansion in a posh district. (The Whistler Mansion, as it came to be known, stood at the corner of Chestnut and Edwards Streets in Springfield, where currently the Wood Museum of History stands.) The Whistlers lived in Springfield until they left the United States in late 1842.

Beginning in 1842, his father was employed to work on a railroad in Russia. After moving to St. Petersburg to join his father a year later, the young Whistler took private art lessons, then enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts at age eleven. The young Artist followed the traditional curriculum of drawing from plaster casts and occasional live Models, reveled in the atmosphere of art talk with older peers, and pleased his parents with a first-class mark in anatomy. In 1844, he met the noted Artist Sir william Allan, who came to Russia with a commission to paint a history of the life of Peter the Great. Whistler's mother noted in her diary, "the great Artist remarked to me 'Your little boy has uncommon genius, but do not urge him beyond his inclination.'"

In 1847-48, his family spent some time in London with relatives, while his father stayed in Russia. Whistler's brother-in-law Francis Haden, a physician who was also an Artist, spurred his interest in art and photography. Haden took Whistler to visit Collectors and to lectures, and gave him a watercolor set with instruction. Whistler already was imagining an art career. He began to collect books on art and he studied other artists' techniques. When his portrait was painted by Sir william Boxall in 1848, the young Whistler exclaimed that the portrait was "very much like me and a very fine picture. Mr. Boxall is a beautiful colourist…It is a beautiful creamy surface, and looks so rich." In his blossoming enthusiasm for art, at fifteen, he informed his father by letter of his Future direction, "I hope, dear father, you will not object to my choice." His father, however, died from cholera at the age of forty-nine, and the Whistler family moved back to his mother's hometown of Pomfret, Connecticut. His art plans remained vague and his Future uncertain. The family lived frugally and managed to get by on a limited income. His cousin reported that Whistler at that time was "slight, with a pensive, delicate face, shaded by soft brown curls…he had a somewhat foreign appearance and manner, which, aided by natural abilities, made him very charming, even at that age."

Whistler was sent to Christ Church Hall School with his mother's hopes that he would become a minister. Whistler was seldom without his sketchbook and was popular with his classmates for his caricatures. However, it became clear that a career in religion did not suit him, so he applied to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where his father had taught drawing and other relatives had attended. He was admitted to the highly selective institution in July 1851 on the strength of his family name, despite his extreme nearsightedness and poor health history. However, during his three years there, his grades were barely satisfactory, and he was a sorry sight at drill and dress, known as "Curly" for his hair length which exceeded regulations. Whistler bucked authority, spouted sarcastic comments, and racked up demerits. Colonel Robert E Lee was the West Point Superintendent and, after considerable indulgence toward Whistler, he had no choice but to dismiss the young cadet. Whistler's major accomplishment at West Point was learning drawing and map making from American Artist Robert W. Weir.

Whistler arrived in Paris in 1855, rented a studio in the Latin Quarter, and quickly adopted the life of a bohemian Artist. Soon, he had a French girlfriend, a dressmaker named Héloise. He studied traditional art methods for a short time at the Ecole Impériale and at the atelier of Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre. The latter was a great advocate of the work of Ingres, and impressed Whistler with two principles that he used for the rest of his career: line is more important than color and that black is the fundamental color of tonal harmony. Twenty years later, the Impressionists would largely overthrow this philosophy, banning black and brown as "forbidden colors" and emphasizing color over form. Whistler preferred self-study (including copying at the Louvre) and enjoying the café life. While letters from home reported his mother's efforts at economy, Whistler spent freely, sold little or nothing in his first year in Paris, and was in steady debt. To relieve the situation, he took to painting and selling copies he made at the Louvre and finally moved to cheaper quarters. As luck would have it, the arrival in Paris of George Lucas, another rich friend, helped stabilize Whistler's finances for a while. In spite of a financial respite, the winter of 1857 was a difficult one for Whistler. His poor health, made worse by excessive smoking and drinking, laid him low.

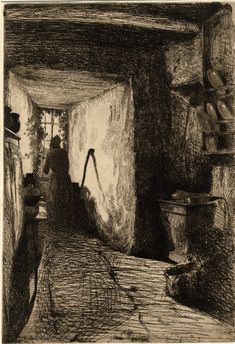

After a year in London, as counterpoint to his 1858 French set, in 1860, he produced another set of etchings called Thames Set, as well as some early impressionistic work, including The Thames in Ice. At this stage, he was beginning to establish his technique of tonal harmony based on a limited, pre-determined palette.

Whistler's famous butterfly signature first developed in the 1860s out of his interest in Asian art. He studied the potter's marks on the china he had begun to collect and decided to design a monogram of his initials. Over time this evolved into the shape of an abstract butterfly. By around 1880, he added a stinger to the butterfly image to create a mark representing both his gentle, sensitive nature and his provocative, feisty spirit. He took great care in the appropriate placement of the image on both his paintings and his custom-made frames. His focus on the importance of balance and harmony extended beyond the frame to the placement of his paintings to their settings, and further to the design of an entire architectural element, as in the Peacock Room.

In 1861, after returning to Paris for a time, Whistler painted his first famous work, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl. The portrait of his mistress and Business manager Joanna Hiffernan was created as a simple study in white; however, others saw it differently. The critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary thought the painting an allegory of a new bride's lost innocence. Others linked it to Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White, a popular novel of the time, or various other literary sources. In England, some considered it a painting in the Pre-Raphaelite manner. In the painting, Hiffernan holds a lily in her left hand and stands upon a bear skin rug (interpreted by some to represent masculinity and lust) with the bear's head staring menacingly at the viewer. The portrait was refused for exhibition at the conservative Royal Academy, but was shown in a private gallery under the title The Woman in White. In 1863 it was shown at the Salon des Refusés in Paris, an event sponsored by Emperor Napoleon III for the exhibition of works rejected from the Salon.

Two years later, Whistler painted another portrait of Hiffernan in white, this time displaying his newfound interest in Asian motifs, which he entitled The Little White Girl. His Lady of the Land Lijsen and The Golden Screen, both completed in 1864, again portray his mistress, in even more emphatic Asian dress and surroundings. During this period Whistler became close to Gustave Courbet, the early leader of the French realist school, but when Hiffernan modeled in the nude for Courbet, Whistler became enraged and his relationship with Hiffernan began to fall apart. In January 1864, Whistler's very religious and very proper mother arrived in London, upsetting her son's bohemian existence and temporarily exacerbating family tensions. As he wrote to Henri Fantin-Latour, "General upheaval!! I had to empty my house and purify it from cellar to eaves." He also immediately moved Hiffernan to another location.

In 1866, Whistler decided to visit Valparaíso, Chile, a journey that has puzzled scholars, although Whistler stated that he did it for political reasons. Chile was at war with Spain and perhaps Whistler thought it a heroic struggle of a small nation against a larger one, but no evidence supports that theory. What the journey did produce was Whistler's first three nocturnal paintings—which he termed "moonlights" and later re-titled as "nocturnes"—night scenes of the harbor painted with a blue or light green palette. After he returned to London, he painted several more nocturnes over the next ten years, many of the River Thames and of Cremorne Gardens, a pleasure park famous for its frequent fireworks displays, which presented a novel challenge to paint. In his maritime nocturnes, Whistler used highly thinned paint as a ground with lightly flicked color to suggest ships, Lights, and shore line. Some of the Thames paintings also show compositional and thematic similarities with the Japanese prints of Hiroshige.

Whistler's lover and model for The White Girl, Joanna Hiffernan, also posed for Gustave Courbet. Historians speculate that Courbet's erotic painting of her as L'Origine du monde led to the breakup of the friendship between Whistler and Courbet. During the 1870s and much of the 1880s, he lived with his model-mistress Maud Franklin. Her ability to endure his long, repetitive sittings helped Whistler develop his portrait skills. He not only made several excellent portraits of her but she was also a helpful stand-in for other sitters.

By 1871, Whistler returned to portraits and soon produced his most famous painting, the nearly monochromatic full-length figure entitled Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, but usually (and incorrectly) referred to as Whistler's Mother. A model failed to appear one day, according to a letter from his mother, so Whistler turned to his mother and suggested that he do her portrait. In his typically slow and experimental way, at first he had her stand, but that proved too tiring so the famous seated pose was adopted. It took dozens of sittings to complete.

At that point, Whistler painted another self-portrait and entitled it Arrangement in Gray: Portrait of the Painter (c. 1872), and he also began to re-title many of his earlier works using terms associated with music, such as a "nocturne", "symphony", "harmony", "study" or "arrangement", to emphasize the tonal qualities and the composition and to de-emphasize the narrative content. Whistler's nocturnes were among his most innovative works. Furthermore, his submission of several nocturnes to art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel after the Franco-Prussian War gave Whistler the opportunity to explain his evolving "theory in art" to artists, buyers, and critics in France. His good friend Fantin-Latour, growing more reactionary in his opinions, especially in his negativity concerning the emerging Impressionist school, found Whistler's new works surprising and confounding. Fantin-Latour admitted, "I don't understand anything there; it's bizarre how one changes. I don't recognize him anymore." Their relationship was nearly at an end by then, but they continued to share opinions in occasional correspondence. When Edgar Degas invited Whistler to exhibit with the first show by the Impressionists in 1874, Whistler turned down the invitation, as did Manet, and some scholars attributed this in part to Fantin-Latour's influence on both men.

Other important portraits by Whistler include those of Thomas Carlyle (historian,1873), Maud Franklin (his mistress, 1876), Cicely Alexander (daughter of a London banker, 1873), Lady Meux (socialite, 1882), and Théodore Duret (critic, 1884). In the 1870s, Whistler painted full-length portraits of F.R. Leyland and his wife Frances. Leyland subsequently commissioned the Artist to decorate his dining room (see Peacock Room below).

Whistler had been disappointed over the irregular acceptance of his works for the Royal Academy exhibitions and the poor hanging and placement of his paintings. In response, Whistler staged his first solo show in 1874. The show was notable and noticed, however, for Whistler's design and decoration of the hall, which harmonized well with the paintings, in keeping with his art theories. A reviewer wrote, "The visitor is struck, on entering the gallery, with a curious sense of harmony and fitness pervading it, and is more interested, perhaps, in the general effect than in any one work."

Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room is Whistler's masterpiece of interior decorative mural art. He painted the paneled room in a rich and unified palette of brilliant blue-greens with over-glazing and metallic gold leaf. Painted in 1876–77, it now is considered a high Example of the Anglo-Japanese style. Unhappy with the first decorative result of the original scheme designed by Thomas Jeckyll (1827-1881), Frederick Leyland left the room in Whistler's care to make minor changes, "to harmonize" the room whose primary purpose was to display Leyland's china collection. Whistler let his imagination run wild, however: "Well, you know, I just painted on. I went on—without design or sketch—putting in every touch with such freedom…And the harmony in blue and gold developing, you know, I forgot everything in my joy of it." He completely painted over 16th-century Cordoba leather wall coverings first brought to Britain by Catherine of Aragon that Leyland had paid £1,000 for.

Whistler had counted on many artists to take his side as witnesses, but they refused, fearing damage to their reputations. The other witnesses for him were unconvincing and the jury's own reaction to the work was derisive. With Ruskin's witnesses more impressive, including Edward Burne-Jones, and with Ruskin absent for medical reasons, Whistler's counter-attack was ineffective. Nonetheless, the jury reached a verdict in favor of Whistler, but awarded a mere farthing in nominal damages, and the court costs were split. The cost of the case, together with huge debts from building his residence ("The White House" in Tite Street, Chelsea, designed with E. W. Godwin, 1877–8), bankrupted him by May 1879, resulting in an auction of his work, collections, and house. Stansky notes the irony that the Fine Art Society of London, which had organized a collection to pay for Ruskin's legal costs, supported him in etching "The Stones of Venice" (and in exhibiting the series in 1883), which helped recoup Whistler's costs.

Whistler, seeing the attack in the newspaper, replied to his friend George Boughton, "It is the most debased style of criticism I have had thrown at me yet." He then went to his solicitor and drew up a writ for libel which was served to Ruskin. Whistler hoped to recover £1,000 plus the costs of the action. The case came to trial the following year after delays caused by Ruskin's bouts of mental illness, while Whistler's financial condition continued to deteriorate. It was heard in the Exchequer Division of the High Court on November 25 and 26 of 1878 before Mr Baron Huddleston and a special jury. Counsel for John Ruskin, Attorney General Sir John Holker, cross-examined Whistler:

During a trip to Venice in 1880, Whistler created a series of etchings and pastels that not only reinvigorated his finances, but also re-energized the way in which artists and Photographers interpreted the city—focusing on the back alleys, side canals, entrance ways, and architectural patterns—and capturing the city's unique atmospherics.

In January 1881, Anna Whistler died. In his mother's honor, thereafter, he publicly adopted her maiden name McNeill as a middle name.

Whistler published his first book, Ten O'clock Lecture in 1885, a major expression of his belief in "art for art's sake". At the time, the opposing Victorian notion reigned, namely, that art, and indeed much human activity, had a moral or social function. To Whistler, however, art was its own end and the artist's responsibility was not to society, but to himself, to interpret through art, and to neither reproduce nor moralize what he saw. Furthermore, he stated, "Nature is very rarely right", and must be improved upon by the Artist, with his own vision.

Whistler joined the Society of British Artists in 1884, and on June 1, 1886, he was elected President. The following year, during Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee, Whistler presented to the Queen, on the Society's behalf, an elaborate album including a lengthy written address and illustrations that he made. Queen Victoria so admired "the beautiful and artistic illumination" that she decreed henceforth, "that the Society should be called Royal." This achievement was widely appreciated by the members, but soon it was overshadowed by the dispute that inevitably arose with the Royal Academy of Arts. Whistler proposed that members of the Royal Society should withdraw from the Royal Academy. This ignited a feud within the membership ranks that overshadowed all other society Business. In May 1888, nine members wrote to Whistler to demand his resignation. At the annual meeting on June 4, he was defeated for reelection by a vote of 18–19, with nine abstentions. Whistler and twenty-five supporters resigned, while the anti-Whistler majority (in his view) was successful in purging him for his "eccentricities" and "non-English" background.

In 1888, Whistler married Beatrice Godwin, (who was called 'Beatrix' or 'Trixie' by Whistler). She was the widow of the Architect E. W. Godwin, who had designed Whistler's White House. Beatrix was the daughter of the Sculptor John Birnie Philip and his wife Frances Black. Beatrix and her sisters Rosalind Birnie Philip and Ethel Whibley posed for many of Whistler's paintings and drawings; with Ethel Whibley being the model for Mother of pearl and silver: The Andalusian (1888–1900). The first five years of their marriage were very happy but her later life was a time of misery for the couple, because of her illness and eventual death from cancer. Near the end, she lay comatose much of the time, completely subdued by morphine, given for pain relief. Her death was a strong blow Whistler never quite overcame. Whistler had several illegitimate children, of whom Charles Hanson is the best documented.After parting from his mistress Joanna Hiffernan, she helped to raise Whistler's son, Charles James Whistler Hanson (1870–1935), the result of an affair with a parlour maid, Louisa Fanny Hanson.By his Common law mistress Maud Franklin Whistler had two daughters: Ione (born circa 1877) and Maud McNeill Whistler Franklin (born 1879). She sometimes referred to herself as 'Mrs. Whistler', and in the census of 1881 gave her name as 'Mary M. Whistler'.

During his life, he affected two generations of artists, in Europe and in the United States. Whistler had significant contact and exchanged ideas and ideals with Realist, Impressionist, and Symbolist Painters. Famous protégés for a time included Walter Sickert and Writer Oscar Wilde. His Tonalism had a profound effect on many American artists, including John Singer Sargent, william Merritt Chase and Willis Seaver Adams (whom he befriended in Venice). Another significant influence was upon Arthur Frank Mathews, whom Whistler met in Paris in the late 1890s. Mathews took Whistler's Tonalism to San Francisco, spawning a broad use of that technique among turn-of-the-century California artists. As American critic Charles Caffin wrote in 1907:

After an indifferent reception to his solo show in London, featuring mostly his nocturnes, Whistler abruptly decided he had had enough of London. He and Trixie moved to Paris in 1892 and resided at n° 110 Rue du Bac, Paris, with his studio at the top of 86 Rue Notre Dame des Champs in Montparnasse. He felt welcomed by Monet, Auguste Rodin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and by Stéphane Mallarmé, and he set himself up a large studio. He was at the top of his career when it was discovered that Trixie had cancer. They returned to London in February 1896, taking rooms at the Savoy Hotel while they sought medical treatment. He made drawings on lithographic transfer paper of the view of the River Thames, from the hotel window or balcony, as he sat with her. She died a few months later.

Whistler's approach to portraiture in his late maturity was described by one of his sitters, Arthur J. Eddy, who posed for the Artist in 1894:

In the final seven years of his life, Whistler did some minimalist seascapes in watercolor and a final self-portrait in oil. He corresponded with his many friends and colleagues. Whistler founded an art school in 1898, but his poor health and infrequent appearances led to its closure in 1901. He died in London on July 17, 1903. He is buried in Chiswick Old Cemetery in west London, adjoining St Nicholas Church, Chiswick.

Having acquired the centerpiece of the room, Whistler's painting of The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, American industrialist and aesthete Charles Lang Freer purchased the entire room in 1904 from Leyland's heirs, including Leyland's daughter and her husband, the British Artist Val Prinsep. Freer then had the contents of the Peacock Room installed in his Detroit mansion. After Freer's death in 1919, The Peacock Room was permanently installed in the Freer Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. The gallery opened to the public in 1923. A large painted caricature by Whistler of Leyland portraying him as an anthropomorphic peacock playing a piano, and entitled The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilthy Lucre - a pun on Leyland's fondness for frilly shirt fronts - is now in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Whistler was the subject of a 1908 biography by his friends, the husband and wife team of Joseph Pennell and Elizabeth Robins Pennell, printmaker and art critic respectively. The Pennells' vast collection of Whistler material was bequeathed to the Library of Congress. The artist's entire estate was left to his sister-in-law Rosalind Birnie Philip. She spent the rest of her life defending his reputation and managing his art and effects, much of which eventually was donated to Glasgow University.

During the Depression, the picture was billed as a "million dollar" painting and was a big hit at the Chicago World's Fair. It was accepted as a universal icon of motherhood by the worldwide public, which was not particularly aware or concerned with Whistler's aesthetic theories. In public recognition of its status and popularity, the United States issued a postage stamp in 1934 featuring an adaptation of the painting.

In 1940 Whistler was commemorated on a United States postage stamp when the U.S. Post Office issued a set of 35 stamps commemorating America's famous Authors, Poets, Educators, Scientists, Composers, Artists, and Inventors: the 'Famous Americans Series'.

A statue of James McNeill Whistler by Nicholas Dimbleby was erected in 2005 at the north end of Battersea Bridge on the River Thames in the United Kingdom.

On October 27, 2010, Swann Galleries set a record price for a Whistler print at auction, when Nocturne, an etching and drypoint printed in black on warm, cream Japan paper, 1879–80 sold for $282,000. It was likely one of the first etchings Whistler made for the Fine Art Society on his arrival in Venice in September 1879 and also one of his most celebrated views of the city.

Whistler had a high-pitched, drawling voice and a unique manner of speech, full of calculated pauses. A friend said, "In a second you discover that he is not conversing—he is sketching in words, giving impressions in sound and sense to be interpreted by the hearer."

In 2015, the New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote that the painting "remains the most important American work residing outside the United States."