| Who is it? | Financier and Banker |

| Birth Day | April 17, 1837 |

| Birth Place | Hartford, United States |

| Age | 182 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | March 31, 1913(1913-03-31) (aged 75)\nRome, Italy |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Resting place | Cedar Hill Cemetery, Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Education | English High School of Boston |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen (B.A.) |

| Occupation | Financier, banker, art collector |

| Spouse(s) | Amelia Sturges (m. 1861; d. 1862) Frances Louise Tracy (m. 1865) |

| Children | Louisa Pierpont Morgan John Pierpont Morgan Jr. Juliet Morgan Anne Morgan |

| Parent(s) | Junius Spencer Morgan Juliet Pierpont |

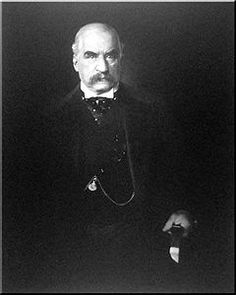

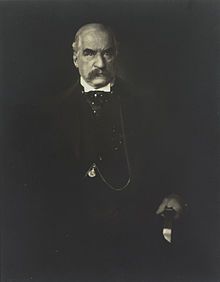

J. P. Morgan, a prominent figure in the world of finance and banking, is estimated to have a net worth of $9 million by 2025. Widely recognized as a brilliant financier and banker, Morgan has left an indelible mark on the United States. His remarkable wealth is a testament to his exceptional acumen in managing financial affairs and establishing successful ventures. Throughout his illustrious career, Morgan has played a pivotal role in shaping the American economy, paving the way for countless innovations and developments. His name has become synonymous with financial expertise and his contributions have had a lasting impact on the nation's financial landscape.

Morgan was born into the influential Morgan family in Hartford, Connecticut, and was raised there. He was the son of Junius Spencer Morgan (1813–1890) and Juliet Pierpont (1816–1884). Pierpont, as he preferred to be known, had a varied education due in part to the plans of his Father. In the fall of 1848, Pierpont transferred to the Hartford Public School and then to the Episcopal Academy in Cheshire, Connecticut (now called Cheshire Academy), boarding with the principal. In September 1851, Morgan passed the entrance exam for The English High School of Boston, a school specializing in mathematics to prepare young men for careers in commerce. In the spring of 1852, an illness struck which was to become more Common as his life progressed. Rheumatic fever left him in so much pain that he could not walk, and Junius sent him to the Azores to recover.

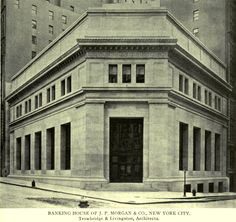

Morgan went into banking in 1857 at the London branch of merchant banking firm Peabody, Morgan & Co., a partnership between his Father and George Peabody founded three years earlier. In 1858, he moved to New York City to join the banking house of Duncan, Sherman & Company, the American representatives of George Peabody and Company. During the American Civil War, in an incident known as the Hall Carbine Affair, Morgan financed the purchase of five thousand rifles from an army arsenal at $3.50 each, which were then resold to a field general for $22 each. Morgan had avoided serving during the war by paying a substitute $300 to take his place. From 1860 to 1864, as J. Pierpont Morgan & Company, he acted as agent in New York for his father's firm, renamed "J.S. Morgan & Co." upon Peabody's retirement in 1864. From 1864–72, he was a member of the firm of Dabney, Morgan, and Company. In 1871, he partnered with the Drexels of Philadelphia to form the New York firm of Drexel, Morgan & Company. At that time, Anthony J. Drexel became Pierpont's mentor at the request of Junius Morgan.

In 1861, Morgan married Amelia Sturges, called Mimi (1835–1862). She died the following year. He married Frances Louisa Tracy, known as Fanny (1842–1924), on May 31, 1865. They had four children:

By the turn of the century, Morgan had become one of America's most important Collectors of gems and had assembled the most important GEM collection in the U.S. as well as of American gemstones (over 1,000 pieces). Tiffany & Co. assembled his first collection under their Chief Gemologist, George Frederick Kunz. The collection was exhibited at the World's Fair in Paris in 1889. The exhibit won two golden awards and drew the attention of important scholars, lapidaries, and the general public.

Morgan was a lifelong member of the Episcopal Church, and by 1890 was one of its most influential Leaders. He was a founding member of the Church Club of New York, an Episcopal private member's club in Manhattan. In 1910, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church established a commission, proposed by Bishop Charles Brent, to implement a world conference of churches to address their differences in their “faith and order.” Morgan was so impressed by the proposal for such a conference that he contributed $100,000 to Finance the commission’s work.

Morgan was a member of the Union Club in New York City. When his friend, Erie Railroad President John King, was black-balled, Morgan resigned and organized the Metropolitan Club of New York. He donated the land on 5th Avenue and 60th Street at a cost of $125,000, and commanded Stanford White to "...build me a club fit for gentlemen, forget the expense..." He invited King in as a charter member and served as club President from 1891 to 1900.

In 1892 Morgan arranged the merger of Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric. He also played important roles in the formation of the United States Steel Corporation, International Harvester and AT&T. At the height of Morgan's career during the early twentieth century, he and his partners had financial Investments in many large corporations and had significant influence over the nation's high Finance and United States Congress members. He directed the banking coalition that stopped the Panic of 1907. He was the leading financier of the Progressive Era, and his dedication to efficiency and modernization helped transform American Business. Adrian Wooldridge characterized Morgan as America's "greatest banker".

His house at 219 Madison Avenue was originally built in 1853 by John Jay Phelps and purchased by Morgan in 1882. It became the first electrically lit private residence in New York. His interest in the new Technology was a result of his financing Thomas Alva Edison's Edison Electric Illuminating Company in 1878. It was there that a reception of 1,000 people was held for the marriage of Juliet Morgan and william Pierson Hamilton on April 12, 1894, where they were given a favorite clock of Morgan's. Morgan also owned East Island in Glen Cove, New York, where he had a large summer house.

Enemies of banking attacked Morgan for the terms of his loan of gold to the federal government in the 1895 crisis and, together with Writer Upton Sinclair, they attacked him for the financial resolution of the Panic of 1907. They also attempted to attribute to him the financial ills of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. In December 1912, Morgan testified before the Pujo Committee, a subcommittee of the House Banking and Currency committee. The committee ultimately concluded that a small number of financial Leaders was exercising considerable control over many industries. The partners of J.P. Morgan & Co. and Directors of First National and National City Bank controlled aggregate resources of $22.245 billion, which Louis Brandeis, later a U.S. Supreme Court Justice, compared to the value of all the property in the twenty-two states west of the Mississippi River.

In 1896, Adolph Simon Ochs owned the Chattanooga Times, and he secured financing from Morgan to purchase the financially struggling New York Times.

George Frederick Kunz continued to build a second, even finer, collection which was exhibited in Paris in 1900. These collections have been donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York where they were known as the Morgan-Tiffany and the Morgan-Bement collections. In 1911 Kunz named a newly found GEM after his best customer, morganite.

U.S. Steel aimed to achieve greater economies of scale, reduce transportation and resource costs, expand product lines, and improve distribution. It was also planned to allow the United States to compete globally with the United Kingdom and Germany. Schwab and others claimed that U.S. Steel's size would allow the company to be more aggressive and effective in pursuing distant international markets ("globalization"). U.S. Steel was regarded as a monopoly by critics, as the Business was attempting to dominate not only steel but also the construction of bridges, ships, railroad cars and rails, wire, nails, and a host of other products. With U.S. Steel, Morgan had captured two-thirds of the steel market, and Schwab was confident that the company would soon hold a 75 percent market share. However, after 1901 the business' market share dropped. Schwab resigned from U.S. Steel in 1903 to form Bethlehem Steel, which became the second largest U.S. steel Producer.

In 1902, J.P. Morgan & Co. financed the formation of International Mercantile Marine Company (IMMC), an Atlantic shipping company which absorbed several major American and British lines in an attempt to monopolize the shipping trade. IMMC was a holding company that controlled subsidiary corporations that had their own operating subsidiaries. Morgan hoped to dominate transatlantic shipping through interlocking directorates and contractual arrangements with the railroads, but that proved impossible because of the unscheduled nature of sea transport, American antitrust legislation, and an agreement with the British government. One of IMMC's subsidiaries was the White Star Line, which owned the RMS Titanic. The ship's famous sinking in 1912, the year before Morgan's death, was a financial disaster for IMMC, which was forced to apply for bankruptcy protection in 1915. Analysis of financial records shows that IMMC was over-leveraged and suffered from inadequate cash flow causing it to default on bond interest payments. Saved by World War I, IMMC eventually re-emerged as the United States Lines, which went bankrupt in 1986.

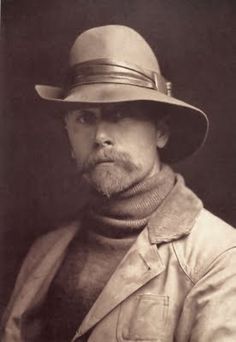

Morgan was a patron to Photographer Edward S. Curtis, offering Curtis $75,000 in 1906, to create a series on the American Indians. Curtis eventually published a 20-volume work entitled The North American Indian. Curtis also produced a motion picture, In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914), which was restored in 1974 and re-released as In the Land of the War Canoes. Curtis was also famous for a 1911 magic lantern slide show The Indian Picture Opera which used his photos and original musical compositions by Composer Henry F. Gilbert.

A delicate political issue arose regarding the brokerage firm of Moore and Schley, which was deeply involved in a speculative pool in the stock of the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company. Moore and Schley had pledged over $6 million of the Tennessee Coal and Iron (TCI) stock for loans among the Wall Street banks. The banks had called the loans, and the firm could not pay. If Moore and Schley should fail, a hundred more failures would follow and then all Wall Street might go to pieces. Morgan decided they had to save Moore and Schley. TCI was one of the chief competitors of U.S. Steel and it owned valuable iron and coal deposits. Morgan controlled U.S. Steel and he decided it had to buy the TCI stock from Moore and Schley. Elbert Gary, head of U.S. Steel, agreed, but was concerned there would be antitrust implications that could cause grave trouble for U.S. Steel, which was already dominant in the steel industry. Morgan sent Gary to see President Theodore Roosevelt, who promised legal immunity for the deal. U.S. Steel thereupon paid $30 million for the TCI stock and Moore and Schley was saved. The announcement had an immediate effect; by November 7, 1907, the panic was over. The crisis underscored the need for a powerful oversight mechanism.

Morgan died while traveling abroad on March 31, 1913, just shy of his 76th birthday. He died in his sleep at the Grand Hotel in Rome, Italy. Flags on Wall Street flew at half-staff, and in an honor usually reserved for heads of state, the stock market closed for two hours when his body passed through New York City. His body was brought to lie in his home and adjacent library the first night of arrival in New York City. His remains were interred in the Cedar Hill Cemetery in his birthplace of Hartford, Connecticut. His son, John Pierpont "Jack" Morgan Jr., inherited the banking Business. He bequeathed his mansion and large book collections to the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.

Morgan was a notable collector of books, pictures, paintings, clocks and other art objects, many loaned or given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (of which he was President and was a major force in its establishment), and many housed in his London house and in his private library on 36th Street, near Madison Avenue in New York City. His son, J. P. Morgan Jr., made the Pierpont Morgan Library a public institution in 1924 as a memorial to his Father, and kept Belle da Costa Greene, his father's private librarian, as its first Director. Morgan was painted by many artists including the Peruvian Carlos Baca-Flor and the Swiss-born American Adolfo Müller-Ury, who also painted a double portrait of Morgan with his favorite grandchild, Mabel Satterlee, that for some years stood on an easel in the Satterlee mansion but has now disappeared.

An avid yachtsman, Morgan owned several large yachts. The well-known quote, "If you have to ask the price, you can't afford it" is commonly attributed to Morgan in response to a question about the cost of maintaining a yacht, although the story is unconfirmed. A similarly unconfirmed legend attributes the quote to his son, J. P. Morgan Jr., in connection with the launching of the son's yacht Corsair IV at Bath Iron Works in 1930.

His son, J. P. Morgan Jr., took over the Business at his father's death, but was never as influential. As required by the 1933 Glass–Steagall Act, the "House of Morgan" became three entities: J.P. Morgan & Co., which later became Morgan Guaranty Trust; Morgan Stanley, an investment house formed by his grandson Henry Sturgis Morgan; and Morgan Grenfell in London, an overseas securities house.

The Cragston Dependencies, associated with his estate, Cragston (at Highlands, New York), was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

Labor policy was a contentious issue. U.S. Steel was non-union, and experienced steel producers, led by Schwab, wanted to keep it that way with the use of aggressive tactics to identify and root out pro-union "troublemakers." The lawyers and Bankers who had organized the merger—notably Morgan and CEO Elbert Gary—were more concerned with long-range profits, stability, good public relations, and avoiding trouble. The bankers' views generally prevailed, and the result was a "paternalistic" labor policy. (U.S. Steel was eventually unionized in the late 1930s.)