| Who is it? | Novelist, Short Story Writer |

| Birth Day | February 05, 1914 |

| Birth Place | St. Louis, Missouri, U.S., United States |

| Age | 106 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | August 2, 1997(1997-08-02) (aged 83)\nLawrence, Kansas, United States |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Pen name | William Lee |

| Occupation | Author |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Genre | Beat literature, paranoid fiction |

| Literary movement | Beat Generation, postmodernism |

| Notable works | Naked Lunch (1959), Junkie (1953) |

| Spouse | Ilse von Klapper (1937–1946) Joan Vollmer (1946–1951) |

| Children | William S. Burroughs Jr. |

| Relatives | William Seward Burroughs I, grandfather Ivy Lee, maternal uncle |

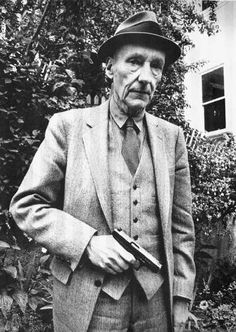

William S. Burroughs, the renowned American novelist and short story writer, is expected to have a net worth of approximately $1.4 million in the year 2025. Burroughs, regarded as one of the most influential writers of the Beat Generation, has made significant contributions to the literary world through his unconventional and avant-garde style. From his groundbreaking novel "Naked Lunch" to his intriguingly dark and surreal stories, Burroughs' works have earned him critical acclaim and a devoted following. Throughout his career, his innovative approach to literature has not only garnered him literary success but also contributed to his estimated net worth.

His parents, upon his graduation, had decided to give him a monthly allowance of $200 out of their earnings from Cobblestone Gardens, a substantial sum in those days. It was enough to keep him going, and indeed it guaranteed his survival for the next twenty-five years, arriving with welcome regularity. The allowance was a ticket to freedom; it allowed him to live where he wanted to and to forgo employment.

Burroughs was born in 1914, the younger of two sons born to Mortimer Perry Burroughs (June 16, 1885 – January 5, 1965) and Laura Hammon Lee (August 5, 1888 – October 20, 1970). His was a prominent family of English ancestry in St. Louis, Missouri. His grandfather, william Seward Burroughs I, founded the Burroughs Adding Machine company, which evolved into the Burroughs Corporation. Burroughs' mother was the daughter of a minister whose family claimed to be closely related to Robert E. Lee. His maternal uncle, Ivy Lee, was an advertising pioneer later employed as a publicist for the Rockefellers. His father ran an antique and gift shop, Cobblestone Gardens in St. Louis; and later in Palm Beach, Florida when they relocated.

Burroughs' parents sold the rights to his grandfather's invention and had no share in the Burroughs Corporation. Shortly before the 1929 stock market crash, they sold their stock for $200,000 (equivalent to approximately $2,850,388 in today's funds).

Burroughs finished high school at Taylor School in Clayton, Missouri, and in 1932, left home to pursue an arts degree at Harvard University, where he was affiliated with Adams House. During the summers, he worked as a cub reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, covering the police docket. He disliked the work, and refused to cover some events, like the death of a drowned child. He lost his virginity in an East St. Louis, Illinois brothel that summer with a female prostitute whom he regularly patronized. While at Harvard, Burroughs made trips to New York City and was introduced to the gay subculture there. He visited lesbian dives, piano bars, and the Harlem and Greenwich Village homosexual underground with Richard Stern, a wealthy friend from Kansas City. They would drive from Boston to New York in a reckless fashion. Once, Stern scared Burroughs so badly that he asked to be let out of the vehicle.

Burroughs graduated from Harvard in 1936. According to Ted Morgan's Literary Outlaw,

After Burroughs graduated from Harvard, his formal education ended, except for brief flirtations with graduate study of anthropology at Columbia and Medicine in Vienna, Austria. He traveled to Europe and became involved in Austrian and Hungarian Weimar-era LGBT culture; he picked up young men in steam baths in Vienna and moved in a circle of exiles, homosexuals, and runaways. There, he met Ilse Klapper, a Jewish woman fleeing the country's Nazi government. The two were never romantically involved, but Burroughs married her, in Croatia, against the wishes of his parents, to allow her to gain a visa to the United States. She made her way to New York City, and eventually divorced Burroughs, although they remained friends for many years. After returning to the United States, he held a string of uninteresting jobs. In 1939, his mental health became a concern for his parents, especially after he deliberately severed the last joint of his left little finger at the knuckle to impress a man with whom he was infatuated. This event made its way into his early fiction as the short story "The Finger."

Burroughs enlisted in the U.S. Army early in 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II. But when he was Classified as a 1-A Infantry, not an officer, he became dejected. His mother recognized her son's depression and got Burroughs a civilian disability discharge —a release from duty based on the premise that he should have not been allowed to enlist due to previous mental instability. After being evaluated by a family friend, who was also a Neurologist at a psychiatric treatment center, Burroughs waited five months in limbo at Jefferson Barracks outside St. Louis before being discharged. During that time he met a Chicago soldier also awaiting release, and once Burroughs was free, he moved to Chicago and held a variety of jobs, including one as an exterminator. When two of his friends from St. Louis, Lucien Carr, a University of Chicago student, and David Kammerer, Carr's admirer, left for New York City, Burroughs followed.

In 1944, Burroughs began living with Joan Vollmer Adams in an apartment they shared with Jack Kerouac and Edie Parker, Kerouac's first wife. Vollmer Adams was married to a G.I. with whom she had a young daughter, Julie Adams. Burroughs and Kerouac got into trouble with the law for failing to report a murder involving Lucien Carr, who had killed David Kammerer in a confrontation over Kammerer's incessant and unwanted advances. This incident inspired Burroughs and Kerouac to collaborate on a novel titled And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, completed in 1945. The two fledgling authors were unable to get it published, but the manuscript was eventually published in November 2008 by Grove Press and Penguin Books.

In any case, he had begun to write in 1945. Burroughs and Kerouac collaborated on And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, a mystery novel loosely based on the Carr/Kammerer situation and that at the time remained unpublished. Years later, in the documentary What Happened to Kerouac?, Burroughs described it as "not a very distinguished work". An excerpt of this work, in which Burroughs and Kerouac wrote alternating chapters, was finally published in Word Virus, a compendium of william Burroughs' writing that was published by his biographer after his death in 1997.

Burroughs fled to Mexico to escape possible detention in Louisiana's Angola state prison. Vollmer and their children followed him. Burroughs planned to stay in Mexico for at least five years, the length of his charge's statute of limitations. Burroughs also attended classes at the Mexico City College in 1950 studying Spanish, as well as "Mexican picture writing" (codices) and the Mayan language with R. H. Barlow.

Much of Burroughs' work is semiautobiographical, primarily drawn from his experiences as a heroin addict, as he lived throughout Mexico City, London, Paris and Tangier in Morocco, as well as from his travels in the South American Amazon. Burroughs accidentally killed his second wife, Joan Vollmer, in 1951 in Mexico City with a pistol during a drunken "William Tell" game; he was consequently convicted of manslaughter. Burroughs found success with his confessional first novel, Junkie (1953), but he is perhaps best known for his third novel Naked Lunch (1959), a highly controversial work that was the subject of a court case after it was challenged as being in violation of the U.S. sodomy laws. With Brion Gysin, he also popularized the literary cut-up technique in works such as The Nova Trilogy (1961–1964).

During 1953, Burroughs was at loose ends. Due to legal problems, he was unable to live in the cities toward which he was most inclined. He spent time with his parents in Palm Beach, Florida, and New York City with Allen Ginsberg. When Ginsberg refused his romantic advances, Burroughs went to Rome to meet Alan Ansen on a vacation financed from his parents' continuing support. When he found Rome and Ansen's company dreary, and inspired by Paul Bowles' fiction, he decided to head for Tangier, Morocco. In a home owned by a known procurer of homosexual prostitutes for visiting American and English men, he rented a room and began to write a large body of text that he personally referred to as Interzone.

To Burroughs, all signs directed a return to Tangier, a city where drugs were freely available and where financial support from his family would continue. He realized that in the Moroccan culture he had found an environment that synchronized with his temperament and afforded no hindrances to pursuing his interests and indulging in his chosen activities. He left for Tangier in November 1954 and spent the next four years there working on the fiction that would later become Naked Lunch, as well as attempting to write commercial articles about Tangier. He sent these writings to Ginsberg, his literary agent for Junkie, but none was published until 1989 when Interzone, a collection of short stories, was published. Under the strong influence of a marijuana confection known as majoun and a German-made opioid called Eukodol, Burroughs settled in to write. Eventually, Ginsberg and Kerouac, who had traveled to Tangier in 1957, helped Burroughs type, edit, and arrange these episodes into Naked Lunch.

Although Burroughs was writing before the shooting of Joan Vollmer, this event marked him and, biographers argue, his work for the rest of his life. Vollmer's death also resonated with Allen Ginsberg, who wrote of her in Dream Record: June 8, 1955, "Joan, what kind of knowledge have the dead? can you still love your mortal acquaintances? What do you remember of us?"

Excerpts from Naked Lunch were first published in the United States in 1958. The novel was initially rejected by City Lights Books, the publisher of Ginsberg's Howl; and Olympia Press publisher Maurice Girodias, who had published English-language novels in France that were controversial for their subjective views of sex and antisocial characters. But Allen Ginsberg managed to get excerpts published in Black Mountain Review and Chicago Review in 1958. Irving Rosenthal, student Editor of Chicago Review, a quarterly journal partially subsidized by the university, promised to publish more excerpts from Naked Lunch, but he was fired from his position in 1958 after Chicago Daily News columnist Jack Mabley called the first excerpt obscene. Rosenthal went on to publish more in his newly created literary journal Big Table No. 1; however, the United States Postmaster General ruled that copies could not be mailed to subscribers on the basis of obscenity laws. John Ciardi did get a copy and wrote a positive review of the work, prompting a telegram from Allen Ginsberg praising the review. This controversy made Naked Lunch interesting to Girodias again, and he published the novel in 1959.

The "Beat Hotel" was a typical European-style boarding house hotel, with Common toilets on every floor, and a small place for personal cooking in the room. Life there was documented by the Photographer Harold Chapman, who lived in the attic room. This shabby, inexpensive hotel was populated by Gregory Corso, Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky for several months after Naked Lunch first appeared. The actual process of publication was partly a function of its "cut-up" presentation to the printer. Girodias had given Burroughs only ten days to prepare the manuscript for print galleys, and Burroughs sent over the manuscript in pieces, preparing the parts in no particular order. When it was published in this authentically random manner, Burroughs liked it better than the initial plan. International rights to the work were sold soon after, and Burroughs used the $3,000 advance from Grove Press to buy drugs (equivalent to approximately $25,000 in today's funds). Naked Lunch was featured in a 1959 Life magazine cover story, partly as an article that highlighted the growing Beat literary movement. During this time Burroughs found an outlet for material otherwise rendered unpublishable in Jeff Nuttall's My Own Mag. Also, some of Burroughs' poetry appeared in the avant garde little magazine Nomad at the beginning of the 1960s.

Numerous bands have found their names in Burroughs' work. The most widely known of these is Steely Dan, a group named after a dildo in Naked Lunch. Also from Naked Lunch came the names Clarknova, The Mugwumps and The Insect Trust. The novel Nova Express inspired the names of Grant Hart's post-Hüsker Dü band Nova Mob, as well as Australian 1960s R&B band Nova Express. British band Soft Machine took its moniker from the Burroughs novel of the same name. Alt-country band Clem Snide is named for a Burroughs character. Thin White Rope took their name from Burroughs' euphemism for ejaculation.

The Word Hoard, the collection of manuscripts that produced Naked Lunch, also produced parts of the later works The Soft Machine (1961), The Ticket That Exploded (1962), and Nova Express (1964). These novels feature extensive use of the cut-up technique that influenced all of Burroughs' subsequent fiction to a degree. During Burroughs' friendship and artistic collaborations with Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville, the technique was combined with images, Gysin's paintings, and sound, via Somerville's tape recorders. Burroughs was so dedicated to the cut-up method that he often defended his use of the technique before editors and publishers, most notably Dick Seaver at Grove Press in the 1960s and Holt, Rinehart & Winston in the 1980s. The cut-up method, because of its random or mechanical basis for text generation, combined with the possibilities of mixing in text written by other Writers, deemphasizes the traditional role of the Writer as creator or originator of a string of words, while simultaneously exalting the importance of the writer's sensibility as an Editor. In this sense, the cut-up method may be considered as analogous to the collage method in the visual arts. New restored editions of The Nova Trilogy (or Cut-Up Trilogy), edited by Oliver Harris and published in 2014, included notes and materials to reveal the care with which Burroughs used his methods and the complex histories of his manuscripts.

After leaving Mexico, Burroughs drifted through South America for several months, seeking out a drug called yagé, which promised to give the user telepathic abilities. A book composed of letters between Burroughs and Ginsberg, The Yage Letters, was published in 1963 by City Lights Books. In 2006, a re-edited version, The Yage Letters Redux, showed that the letters were largely fictionalised from Burroughs' notes.

Burroughs played Opium Jones in the 1966 Conrad Rooks cult film Chappaqua, which also featured cameo roles by Allen Ginsberg, Moondog, and others. In 1968, an abbreviated—77 minutes as opposed to the original's 104 minutes—version of Benjamin Christensen's 1922 film Häxan was released, subtitled Witchcraft Through The Ages. This version, produced by Antony Balch, featured an eclectic jazz score by Daniel Humair and expressionist narration by Burroughs. He also appeared alongside Brion Gysin in a number of short films in the 1960s directed by Balch. Jack Sargeant's book Naked Lens: Beat Cinema details Burroughs film work at length, covering his collaborations with Balch and Burroughs' theories of film.

Burroughs appears in the first part of The Illuminatus! Trilogy by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson during the 1968 Democratic National Convention riots and is described as a person devoid of anger, passion, indignation, hope, or any other recognizable human emotion. He is presented as a polar opposite of Allen Ginsberg, as Ginsberg believed in everything and Burroughs believed in nothing. Wilson would recount in his Cosmic Trigger II: Down to Earth having interviewed both Burroughs and Ginsberg for Playboy the day the riots began, as well as his experiences with Shea during the riots, providing some detail on the creation of the fictional sequence.

Burroughs supported himself and his addiction by publishing pieces in small literary presses. His avant-garde reputation grew internationally as hippies and college students discovered his earlier works. He developed a close friendship with Antony Balch and lived with a young hustler named John Brady who continuously brought home young women despite Burroughs' protestations. In the midst of this personal turmoil, Burroughs managed to complete two works: a novel written in screenplay format, The Last Words of Dutch Schultz (1969); and the traditional prose-format novel The Wild Boys (1971).

Burroughs continues to be named as an influence by contemporary Writers of fiction. Both the New Wave and, especially, the cyberpunk schools of science fiction are indebted to him. Admirers from the late 1970s—early 1980s milieu of this subgenre include william Gibson and John Shirley, to name only two. First published in 1982, the British slipstream fiction magazine Interzone (which later evolved into a more traditional science fiction magazine) paid tribute to him with its choice of name. He is also cited as a major influence by Musicians Roger Waters, David Bowie, Patti Smith, Genesis P-Orridge, Ian Curtis, Lou Reed, Laurie Anderson, Tom Waits and Kurt Cobain.

In 1974, concerned about his friend's well-being, Allen Ginsberg gained for Burroughs a contract to teach creative writing at the City College of New York. Burroughs successfully withdrew from heroin use and moved to New York. He eventually found an apartment, affectionately dubbed "The Bunker", on the Lower East Side of Manhattan at 222 Bowery. The dwelling was a partially converted YMCA gym, complete with lockers and communal showers. The building fell within New York City rent control policies that made it extremely cheap; it was only about four hundred dollars a month until 1981 when the rent control rules changed, doubling the rent overnight. Burroughs added "teacher" to the list of jobs he did not like, as he lasted only a semester as a professor; he found the students uninteresting and without much creative talent. Although he needed income desperately, he turned down a teaching position at the University at Buffalo for $15,000 a semester. "The teaching gig was a lesson in never again. You were giving out all this Energy and nothing was coming back." His savior was the newly arrived, twenty-one-year-old bookseller and Beat Generation devotee James Grauerholz, who worked for Burroughs part-time as a secretary as well as in a bookstore. Grauerholz suggested the idea of reading tours. Grauerholz had managed several rock bands in Kansas and took the lead in booking for Burroughs reading tours that would help support him throughout the next two decades. It raised his public profile, eventually aiding in his obtaining new publishing contracts. Through Grauerholz, Burroughs became a monthly columnist for the noted popular culture magazine Crawdaddy, for which he interviewed Led Zeppelin's Jimmy Page in 1975. Burroughs decided to relocate back to the United States permanently in 1976. He then began to associate with New York cultural players such as Andy Warhol, John Giorno, Lou Reed, Patti Smith, and Susan Sontag, frequently entertaining them at the Bunker; he also visited venues like CBGB to watch the likes of Patti Smith perform. Throughout early 1977, Burroughs collaborated with Southern and Dennis Hopper on a screen adaptation of Junky. Financed by a reclusive acquaintance of Burroughs, the project lost traction after financial problems and creative disagreements between Hopper and Burroughs.

In 1976, Billy Burroughs was eating dinner with his father and Allen Ginsberg in Boulder, Colorado, at Ginsberg's Buddhist poetry school (Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics) at Chogyam Trungpa's Naropa University when he began to vomit blood. Burroughs senior had not seen his son for over a year and was alarmed at his appearance when Billy arrived at Ginsberg's apartment. Although Billy had successfully published two short novels in the 1970s, and was deemed by literary critics like Ann Charters as a bona fide "second generation beat writer", his brief marriage to a teenage waitress had disintegrated. Billy was a constant drinker, and there were long periods when he was out of contact with any of his family or friends. The diagnosis was liver cirrhosis so complete that the only treatment was a rarely performed liver transplant operation. Fortunately, the University of Colorado Medical Center was one of two places in the nation that performed transplants under the pioneering work of Dr. Thomas Starzl. Billy underwent the procedure and beat the thirty-percent survival odds. His father spent time in 1976 and 1977 in Colorado, helping Billy through additional surgeries and complications. Ted Morgan's biography asserts that their relationship was not spontaneous and lacked real warmth or intimacy. Allen Ginsberg was supportive to both Burroughs and his son throughout the long period of recovery.

Organized by Columbia professor Sylvère Lotringer, Giorno, and Grauerholz, the Nova Convention was a multimedia retrospective of Burroughs' work held from November 30 to December 2, 1978, at various locations throughout New York. The event included readings from Southern, Ginsberg, Smith, and Frank Zappa (who filled in at the last minute for Keith Richards, then entangled in a legal problem), in addition to panel discussions with Timothy Leary and Robert Anton Wilson and concerts featuring The B-52's, Suicide, Philip Glass, and Debbie Harry and Chris Stein.

Burroughs, by 1979, was once again addicted to heroin. The cheap heroin that was easily purchased outside his door on the Lower East Side "made its way" into his veins, coupled with "gifts" from the overzealous if well-intentioned admirers who frequently visited the Bunker. Although Burroughs would have episodes of being free from heroin, from this point until his death he was regularly addicted to the drug. He died in 1997 on a methadone maintenance program. In an introduction to Last Words: The Final Journals of william S. Burroughs, James Grauerholz (who managed Burroughs' reading tours in the 1980s and 1990s) mentions that part of his job was to deal with the "underworld" in each city to secure the author's needed drugs.

Burroughs narrated part of the 1980 documentary Shamans of the Blind Country by Anthropologist and filmmaker Michael Oppitz. He gave a reading on Saturday Night Live on November 7, 1981, in an episode hosted by Lauren Hutton.

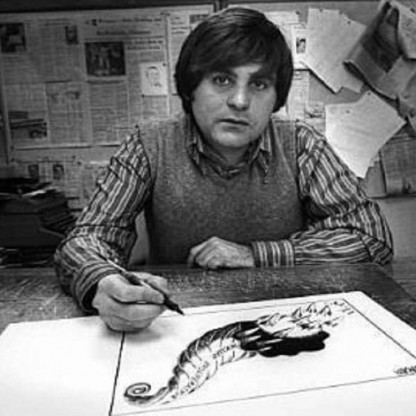

During 1982, Burroughs developed a painting technique whereby he created abstract compositions by placing spray paint cans some distance in front of blank surfaces, and then shooting at the paint cans with a shotgun. These splattered and shot panels and canvasses were first exhibited in the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York City in 1987. By this time he had developed a comprehensive visual art practice, using ink, spray paint, collage and unusual things such as mushrooms and plungers to apply the paint. He created file-folder paintings featuring these mediums as well as "automatic calligraphy" inspired by Brion Gysin. He originally used the folders to mix pigments before observing that they could be viewed as art in themselves. He also used many of these painted folders to store manuscripts and correspondence in his personal archive Until his last years, he prolifically created visual art. Burroughs' work has since been featured in more than fifty international galleries and museums including Royal Academy of the Arts, Centre Pompidou, Guggenheim Museum, ZKM Karlsruhe, Sammlung Falckenberg, New Museum, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Los Angeles County Museum, and Whitney Museum of American Art.

Filmmakers Lars Movin and Steen Moller Rasmussen used footage of Burroughs taken during a 1983 tour of Scandinavia in the documentary Words of Advice: william S. Burroughs on the Road. A 2010 documentary, William S. Burroughs: A Man Within, was made for Independent Lens on PBS.

Burroughs reads a passage from his novel Nova Express during the bridge of the title song from Todd Tamanend Clark's 1984 album Into The Vision, which also features Cheetah Chrome from The Dead Boys on guitar.

Burroughs said in his 1985 introduction to Queer that shooting Vollmer was a pivotal event in his life, and one which provoked his writing:

Burroughs created visual art throughout his life-time, but never exhibited it until 1987, after the death of his friend and collaborator Brion Gysin. For the next and last 10 years of his life, he presented his paintings and drawings at museums and galleries worldwide.

Burroughs subsequently made cameo appearances in a number of other films and videos, such as David Blair's Wax or the Discovery of Television Among the Bees, an elliptic story about the first Gulf War in which Burroughs plays a beekeeper, and Decoder by Klaus Maeck. He played an aging junkie priest in Gus Van Sant's 1989 film Drugstore Cowboy. He also appears briefly at the beginning of Van Sant's Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (based on the Tom Robbins novel), in which he is seen crossing a city street; as the noise of the city rises around him he pauses in the middle of the intersection and speaks the single word "ominous". Van Sant's short film "Thanksgiving Prayer" features Burroughs reading the poem "Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 28, 1986", from Tornado Alley, intercut with a collage of black and white images.

In 1990, Island Records released Dead City Radio, a collection of readings set to a broad range of musical compositions. It was produced by Hal Willner and Nelson Lyon, with musical accompaniment from John Cale, Donald Fagen, Lenny Pickett, Chris Stein, Sonic Youth, and others. The remastered edition of Sonic Youth's album Goo includes a longer version of "Dr. Benway's House", which had appeared, in shorter form, on Dead City Radio.

Burroughs was fictionalized in Jack Kerouac's autobiographical novel On the Road as "Old Bull Lee". He also makes an appearance in J. G. Ballard's semi-autobiographical 1991 novel The Kindness of Women. In the 2004 novel Move Under Ground, Burroughs, Kerouac, and Neal Cassady team up to defeat Cthulhu.

In 1992 Burroughs worked with The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy on Spare Ass Annie and Other Tales, with the duo providing musical background and accompaniment to Burroughs' spoken readings from several of his books. A 12" Ep was released with five different remixes of the Spare Ass Annie track Words of Advice for Young People, all done by Bill Laswell.

He became a member of a chaos magic organization, the Illuminates of Thanateros, in 1993.

Since 1997, several posthumous collections of Burroughs' work have been published. A few months after his death, a collection of writings spanning his entire career, Word Virus, was published (according to the book's introduction, Burroughs himself approved its contents prior to his death). Aside from numerous previously released pieces, Word Virus also included what was promoted as one of the few surviving fragments of And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, a novel by Burroughs and Kerouac (later published in 2008). A collection of journal entries written during the final months of Burroughs' life was published as the book Last Words in 2000. Publication of a memoir by Burroughs entitled Evil River by Viking Press has been delayed several times; after initially being announced for a 2005 release, online booksellers indicated a 2007 release, complete with an ISBN number (ISBN 0670813516), but it remains unpublished. In December 2007, Ohio State University Press released Everything Lost: The Latin American Journals of william S. Burroughs. Edited by Oliver Harris, the book contains transcriptions of journal entries made by Burroughs during the time of composing Queer and The Yage Letters, with cover art and review information. In addition, restored editions of numerous texts have been published in recent years, all containing additional material and essays on the works. The complete Kerouac/Burroughs manuscript And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks was published for the first time in November 2008.

Burroughs was portrayed by Kiefer Sutherland in the 2000 film Beat, written and directed by Gary Walkow. Loosely biographical, the plot involves a car trip to Mexico City with Vollmer, Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Lucien Carr, and includes a scene of Vollmer's shooting.

Drugs, homosexuality, and death, Common among Burroughs' themes, have been taken up by Dennis Cooper, of whom Burroughs said, "Dennis Cooper, God help him, is a born writer". Cooper, in return, wrote, in his essay 'King Junk', "along with Jean Genet, John Rechy, and Ginsberg, [Burroughs] helped make homosexuality seem cool and highbrow, providing gay liberation with a delicious edge". Splatterpunk Writer Poppy Z. Brite has frequently referenced this aspect of Burroughs' work. Burroughs' writing continues to be referenced years after his death; for Example, a November 2004 episode of the TV series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation included an evil character named Dr. Benway (named for an amoral physician who appears in a number of Burroughs' works.) This is an echo of the hospital scene in the movie Repo Man, made during Burroughs' life-time, in which both Dr. Benway and Mr. Lee (a Burroughs pen name) are paged.

The 25th anniversary edition of Queer published in 2010, edited by Oliver Harris, called into question Burroughs' claim, and clarified the importance for Queer of Burroughs' traumatic relationship with the boyfriend fictionalized in the story as Eugene Allerton, rather than the shooting of Vollmer.

Burroughs is portrayed by Ben Foster in the 2013 film Kill Your Darlings, directed by John Krokidas and written by John Krokidas and Austin Bunn. The film tells the story of Lucien Carr (Dane DeHaan) and David Kammerer (Michael C. Hall), with appearances by actors playing Ginsberg (Daniel Radcliffe) and Kerouac (Jack Huston).

Burroughs used photography extensively throughout his career, both as a recording medium in planning his writings, and as a significant dimension of his own artistic practice, in which photographs and other images feature as significant elements in cut-ups. With Ian Sommerville, he experimented with photography's potential as a form of memory-device, photographing and rephotographing his own pictures in increasingly complex time-image arrangements. (See: Patricia Allmer and John Sears (ed.) Taking Shots: The Photography of william S. Burroughs, London: Prestel and The Photographers' Gallery, 2014).

Burroughs appears in Paul La Farge's 2017 novel The Night Ocean, as a student and acquaintance of R. H. Barlow in Mexico City. Barlow was an Anthropologist, poet, and author, as well as the friend and literary executor of H. P. Lovecraft.