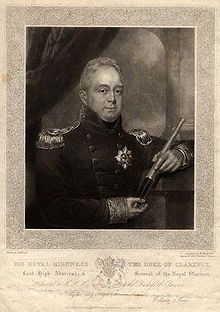

| Who is it? | King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover |

| Birth Day | August 21, 1765 |

| Birth Place | Buckingham Palace, British |

| Age | 254 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 20 June 1837(1837-06-20) (aged 71)\nWindsor Castle, Berkshire |

| Birth Sign | Virgo |

| Reign | 26 June 1830 – 20 June 1837 |

| Coronation | 8 September 1831 |

| Predecessor | George IV |

| Successor | Ernest Augustus |

| Prime Ministers | See list Duke of Wellington Earl Grey Viscount Melbourne Robert Peel |

| Burial | 8 July 1837 St George's Chapel, Windsor |

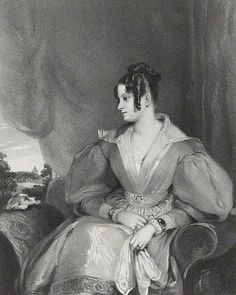

| Spouse | Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen |

| Issue more... | Legitimate: Princess Charlotte of Clarence Princess Elizabeth of Clarence Illegitimate: George FitzClarence, Earl of Munster Henry FitzClarence Sophia Sidney, Baroness De L'Isle and Dudley Lady Mary Fox Lord Frederick FitzClarence Elizabeth Hay, Countess of Erroll Lord Adolphus FitzClarence Lady Augusta Gordon Lord Augustus FitzClarence Amelia Cary, Viscountess Falkland |

| Full name | Full name William Henry William Henry |

| House | Hanover |

| Father | George III of the United Kingdom |

| Mother | Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

| Religion | Anglican |

| Occupation | Military (Naval) |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/branch | Royal Navy (active service) |

| Years of service | 1779–1790 (active service) |

| Rank | Rear-Admiral (active service) |

| Commands held | HMS Andromeda HMS Pegasus |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Cape St Vincent |

William IV of the United Kingdom, also known as the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover in British history, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2025. Despite his royal status and influence, William IV's net worth is relatively modest compared to modern-day monarchs. However, it is important to note that estimating the net worth of historical figures can be challenging due to the lack of precise financial records from that era.

William was born in the early hours of the morning on 21 August 1765 at Buckingham House, the third child and son of King George III and Queen Charlotte. He had two elder brothers, George and Frederick, and was not expected to inherit the Crown. He was baptised in the Great Council Chamber of St James's Palace on 20 September 1765. His godparents were his paternal uncles, the Duke of Gloucester and Prince Henry (later Duke of Cumberland), and his paternal aunt, Princess Augusta, then hereditary Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel.

William was part of the first generation to grow to maturity under the Royal Marriages Act 1772, which forbade descendants of George II from marrying unless they either obtained the monarch's consent or, if over the age of 25, gave twelve months' notice to the Privy Council. Several of George III's sons, including william, chose to cohabit with the women they loved, rather than seek a wife. Having legitimate issue was not a primary concern for william, as he was one of the younger sons of George III, he was not expected to figure in the succession, which was considered secure once the Prince of Wales married and had a daughter, Princess Charlotte, second-in-line to the throne.

He spent most of his early life in Richmond and at Kew Palace, where he was educated by private tutors. At the age of thirteen, he joined the Royal Navy as a midshipman, and was present at the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1780. His experiences in the navy seem to have been little different from those of other midshipmen, though in contrast to other sailors he was accompanied on board ships by a tutor. He did his share of the cooking and got arrested with his shipmates after a drunken brawl in Gibraltar; he was hastily released from custody after his identity became known.

As a son of the sovereign, william was granted the use of the royal arms (without the electoral inescutcheon in the Hanoverian quarter) in 1781, differenced by a label of three points argent, the centre point bearing a cross gules, the outer points each bearing an anchor azure. In 1801 his arms altered with the royal arms, however the marks of difference remained the same.

William IV had a short but eventful reign. In Britain, the Reform Crisis marked the ascendancy of the House of Commons and the corresponding decline of the House of Lords, and the King's unsuccessful attempt to remove the Melbourne ministry indicated a reduction in the political influence of the Crown and of the King's influence with the people. During the reign of George III, the King could have dismissed one ministry, appointed another, dissolved Parliament, and expected the people to vote in favour of the new administration. Such was the result of a dissolution in 1784, after the dismissal of the Fox-North Coalition, and in 1807, after the dismissal of Lord Grenville. But when william IV dismissed the Melbourne ministry, the Tories under Sir Robert Peel failed to win the ensuing elections. The monarch's ability to influence the opinion of the people, and therefore national policy, had been reduced. None of William's successors has attempted to remove a government or to appoint another against the wishes of Parliament. william understood that as a constitutional monarch he had no power to act against the opinion of Parliament. He said, "I have my view of things, and I tell them to my ministers. If they do not adopt them, I cannot help it. I have done my duty."

He became a lieutenant in 1785 and captain of HMS Pegasus the following year. In late 1786, he was stationed in the West Indies under Horatio Nelson, who wrote of William: "In his professional line, he is superior to two-thirds, I am sure, of the [Naval] list; and in attention to orders, and respect to his superior officer, I hardly know his equal." The two were great friends, and dined together almost nightly. At Nelson's wedding, william insisted on giving the bride away. He was given command of the frigate HMS Andromeda in 1788, and was promoted to rear-admiral in command of HMS Valiant the following year.

William sought to be made a duke like his elder brothers, and to receive a similar parliamentary grant, but his father was reluctant. To put pressure on him, william threatened to stand for the House of Commons for the constituency of Totnes in Devon. Appalled at the prospect of his son making his case to the voters, George III created him Duke of Clarence and St Andrews and Earl of Munster on 16 May 1789, supposedly saying: "I well know it is another vote added to the Opposition." William's political record was inconsistent and, like many politicians of the time, cannot be certainly ascribed to a single party. He allied himself publicly with the Whigs as well as his elder brothers George, Prince of Wales, and Frederick, Duke of York, who were known to be in conflict with the political positions of their father.

William ceased his active Service in the Royal Navy in 1790. When Britain declared war on France in 1793, he was anxious to serve his country and expected a command, but was not given a ship, perhaps at first because he had broken his arm by falling down some stairs drunk, but later perhaps because he gave a speech in the House of Lords opposing the war. The following year he spoke in favour of the war, expecting a command after his change of heart; none came. The Admiralty did not reply to his request. He did not lose hope of being appointed to an active post. In 1798 he was made an admiral, but the rank was purely nominal. Despite repeated petitions, he was never given a command throughout the Napoleonic Wars. In 1811, he was appointed to the honorary position of Admiral of the Fleet. In 1813, he came nearest to any actual fighting, when he visited the British troops fighting in the Low Countries. Watching the bombardment of Antwerp from a church steeple, he came under fire, and a bullet pierced his coat.

Before he met Mrs. Jordan, william had an illegitimate son whose mother is unknown; the son, also called william, drowned off Madagascar in HMS Blenheim in February 1807. Caroline von Linsingen, whose father was a general in the Hanoverian infantry, claimed to have had a son, Heinrich, by william in around 1790 but william was not in Hanover at the time that she claims and the story is considered implausible by historians.

William appeared to enjoy the domesticity of his life with Mrs. Jordan, remarking to a friend: "Mrs. Jordan is a very good creature, very domestic and careful of her children. To be sure she is absurd sometimes and has her humours. But there are such things more or less in all families." The couple, while living quietly, enjoyed entertaining, with Mrs. Jordan writing in late 1809: "We shall have a full and merry house this Christmas, 'tis what the dear Duke delights in." George III was accepting of his son's relationship with the Actress (though recommending that he halve her allowance); in 1797, he created william Ranger of Bushy Park, which included a large residence, Bushy House, for William's growing family. william used Bushy as his principal residence until he became king. His London residence, Clarence House, was constructed to the designs of John Nash between 1825 and 1827.

William's elder brother, the Prince of Wales, had been Prince Regent since 1811 because of the mental illness of their father, George III. In 1820, the King died, leaving the Crown to the Prince Regent, who became George IV. william, Duke of Clarence, was now second in the line of succession, preceded only by his brother, Frederick, Duke of York. Reformed since his marriage, william walked for hours, ate relatively frugally, and the only drink he imbibed in quantity was barley water flavoured with lemon. Both of his older brothers were unhealthy, and it was considered only a matter of time before he became king. When the Duke of York died in 1827, william, then more than 60 years old, became heir presumptive. Later that year, the incoming Prime Minister, George Canning, appointed him to the office of Lord High Admiral, which had been in commission (that is, exercised by a board rather than by a single individual) since 1709. While in office, william had repeated conflicts with his Council, which was composed of Admiralty officers. Things finally came to a head in 1828 when, as Lord High Admiral, he put to sea with a squadron of ships, leaving no word of where they were going, and remaining away for ten days. The King, through the Prime Minister, by now Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, requested his resignation; he complied.

Deeply in debt, william made multiple attempts at marrying a wealthy heiress such as Catherine Tylney-Long, but his suits were unsuccessful. Following the death of William's niece Princess Charlotte of Wales, then second-in-line to the British throne, in 1817, the king was left with twelve children, but no legitimate grandchildren. The race was on among the royal dukes to marry and produce an heir. william had great advantages in this race—his two older brothers were both childless and estranged from their wives, who were both beyond childbearing age anyway, and william was the healthiest of the three. If he lived long enough, he would almost certainly ascend the British and Hanoverian thrones, and have the opportunity to sire the next monarch. William's initial choices of potential wives either met with the disapproval of his eldest brother, the Prince of Wales, or turned him down. William's younger brother Adolphus, the Duke of Cambridge, was sent to Germany to scout out the available Protestant princesses; he came up with Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel, but her father Frederick declined the match. Two months later, the Duke of Cambridge married Augusta himself. Eventually, a Princess was found who was amiable, home-loving, and was willing to accept, even enthusiastically welcoming William's nine surviving children, several of whom had not yet reached adulthood. In the Drawing Room at Kew Palace on 11 July 1818, william married Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, the daughter of George I, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen. At 25, Adelaide was half William's age.

At the time, the death of the monarch required fresh elections and, in the general election of 1830, Wellington's Tories lost ground to the Whigs under Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, though the Tories still had the largest number of seats. With the Tories bitterly divided, Wellington was defeated in the House of Commons in November, and Lord Grey formed a government. Grey pledged to reform the electoral system, which had seen few changes since the fifteenth century. The inequities in the system were great; for Example, large towns such as Manchester and Birmingham elected no members (though they were part of county constituencies), while small boroughs, known as rotten or pocket boroughs—such as Old Sarum with just seven voters—elected two members of Parliament each. Often, the rotten boroughs were controlled by great aristocrats, whose nominees were invariably elected by the constituents—who were, most often, their tenants—especially since the secret ballot was not yet used in Parliamentary elections. Landowners who controlled seats were even able to sell them to prospective candidates.

After the rejection of the Second Reform Bill by the Upper House in October 1831, agitation for reform grew across the country; demonstrations grew violent in so-called "Reform Riots". In the face of popular excitement, the Grey ministry refused to accept defeat in the House of Lords, and re-introduced the Bill, which still faced difficulties in the House of Lords. Frustrated by the Lords' recalcitrance, Grey suggested that the King create a sufficient number of new peers to ensure the passage of the Reform Bill. The King objected—though he had the power to create an unlimited number of peers, he had already created 22 new peers in his Coronation Honours. william reluctantly agreed to the creation of the number of peers sufficient "to secure the success of the bill". However, the King, citing the difficulties with a permanent expansion of the peerage, told Grey that the creations must be restricted as much as possible to the eldest sons and collateral heirs of existing peers, so that the created peerages would eventually be absorbed as subsidiary titles. This time, the Lords did not reject the bill outright, but began preparing to change its basic character through amendments. Grey and his fellow ministers decided to resign if the King did not agree to an immediate and large creation to force the bill through in its entirety. The King refused, and accepted their resignations. The King attempted to restore the Duke of Wellington to office, but Wellington had insufficient support to form a ministry and the King's popularity sank to an all-time low. Mud was slung at his carriage and he was publicly hissed. The King agreed to reappoint Grey's ministry, and to create new peers if the House of Lords continued to pose difficulties. Concerned by the threat of the creations, most of the bill's opponents abstained and the Reform Act 1832 was passed. The mob blamed William's actions on the influence of his wife and brother, and his popularity recovered.

Public perception in Germany was that Britain dictated Hanoverian policy. This was not the case. In 1832, Metternich introduced laws that curbed fledgling liberal movements in Germany. Britain's Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston opposed this, and sought William's influence to cause the Hanoverian government to take the same position. The Hanoverian government instead agreed with Metternich, much to Palmerston's dismay, and william declined to intervene. The conflict between william and Palmerston over Hanover was renewed the following year when Metternich called a conference of the German states, to be held in Vienna, and Palmerston wanted Hanover to decline the invitation. Instead, the Viceroy accepted, backed fully by william.

During his reign the British Parliament enacted major reforms, including the Factory Act of 1833 (preventing child labour), the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (emancipating slaves in the colonies), and the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (standardising provision for the destitute). william attracted criticism from reformers, who felt that reform did not go far enough, and from reactionaries, who felt that reform went too far. A modern interpretation sees him as failing to satisfy either political extreme by trying to find compromise between two bitterly opposed factions, but in the process proving himself more capable as a constitutional monarch than many had supposed.

In November 1834, the Leader of the House of Commons and Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Charles Spencer, Viscount Althorp, inherited a peerage, thus removing him from the House of Commons to the Lords. Melbourne had to appoint a new Commons leader and a new Chancellor (who by long custom, must be drawn from the Commons), but the only candidate whom Melbourne felt suitable to replace Althorp as Commons leader was Lord John Russell, who william (and many others) found unacceptable due to his radical politics. william claimed that the ministry had been weakened beyond repair and used the removal of Lord Althorp—who had previously indicated that he would retire from politics upon becoming a peer—as the pretext for the dismissal of the entire ministry. With Lord Melbourne gone, william chose to entrust power to a Tory, Sir Robert Peel. Since Peel was then in Italy, the Duke of Wellington was provisionally appointed Prime Minister. When Peel returned and assumed leadership of the ministry for himself, he saw the impossibility of governing because of the Whig majority in the House of Commons. Consequently, Parliament was dissolved to force fresh elections. Although the Tories won more seats than in the previous election, they were still in the minority. Peel remained in office for a few months, but resigned after a series of parliamentary defeats. Lord Melbourne was restored to the Prime Minister's office, remaining there for the rest of William's reign, and the King was forced to accept Russell as Commons leader.

Both the King and Queen were fond of their niece, Princess Victoria of Kent. Their attempts to forge a close relationship with the girl were frustrated by the conflict between the King and the Duchess of Kent, the young princess's widowed mother. The King, angered at what he took to be disrespect from the Duchess to his wife, took the opportunity at what proved to be his final birthday banquet in August 1836 to settle the score. Speaking to those assembled at the banquet, who included the Duchess and Princess Victoria, william expressed his hope that he would survive until Princess Victoria was 18 so that the Duchess of Kent would never be regent. He said, "I trust to God that my life may be spared for nine months longer ... I should then have the satisfaction of leaving the exercise of the Royal authority to the personal authority of that young lady, heiress presumptive to the Crown, and not in the hands of a person now near me, who is surrounded by evil advisers and is herself incompetent to act with propriety in the situation in which she would be placed." The speech was so shocking that Victoria burst into tears, while her mother sat in silence and was only with difficulty persuaded not to leave immediately after dinner (the two left the next day). William's outburst undoubtedly contributed to Victoria's tempered view of him as "a good old man, though eccentric and singular". william survived, though mortally ill, to the month after Victoria's coming of age. "Poor old man!", Victoria wrote as he was dying, "I feel sorry for him; he was always personally kind to me."

Queen Adelaide attended the dying william devotedly, not going to bed herself for more than ten days. william IV died in the early hours of the morning of 20 June 1837 at Windsor Castle, where he was buried. As he had no living legitimate issue, the Crown of the United Kingdom passed to Princess Victoria of Kent, the only child of Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent, George III's fourth son. Under Salic Law, a woman could not rule Hanover, and so the Hanoverian Crown went to George III's fifth son, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. William's death thus ended the personal union of Britain and Hanover, which had persisted since 1714. The main beneficiaries of his will were his eight surviving children by Mrs. Jordan. Although william IV is not the direct ancestor of the later monarchs of the United Kingdom, he has many notable descendants through his illegitimate family with Mrs. Jordan, including former Prime Minister David Cameron, TV presenter Adam Hart-Davis, author and statesman Duff Cooper, and the first Duke of Fife, who married Queen Victoria's granddaughter Louise.

The King had a mixed relationship with Lord Melbourne. Melbourne's government mooted more ideas to introduce greater democracy, such as the devolution of powers to the Legislative Council of Lower Canada, which greatly alarmed the King, who feared it would eventually lead to the loss of the colony. At first, the King bitterly opposed these proposals. william exclaimed to Lord Gosford, Governor General-designate of Canada: "Mind what you are about in Canada ... mind me, my Lord, the Cabinet is not my Cabinet; they had better take care or by God, I will have them impeached." When William's son Augustus FitzClarence enquired of his father whether the King would be entertaining during Ascot week, william gloomily replied, "I cannot give any dinners without inviting the ministers, and I would rather see the devil than any one of them in my house." Nevertheless, william approved the Cabinet's recommendations for reform. Despite his disagreements with Lord Melbourne, the King wrote warmly to congratulate the Prime Minister when he triumphed in the adultery case brought against him concerning Lady Caroline Norton—he had refused to permit Melbourne to resign when the case was first brought. The King and Prime Minister eventually found a modus vivendi; Melbourne applying tact and firmness when called for; while william realised that his First Minister was far less radical in his politics than the King had feared.