| Birth Day | December 29, 1809 |

| Birth Place | Liverpool, British |

| Age | 210 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 19 May 1898(1898-05-19) (aged 88)\nHawarden Castle, Wales |

| Birth Sign | Capricorn |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Thomas Wilde |

| Succeeded by | John Stuart |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Political party | Tory (1828–34) Conservative (1834–46) Peelite (1846–59) Liberal (1859–98) |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine Glynne (m. 1839) |

| Children | William, Agnes, Stephen, Catherine, Mary, Helen, Henry, Herbert |

| Parents | Sir John Gladstone Anne MacKenzie Robertson |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

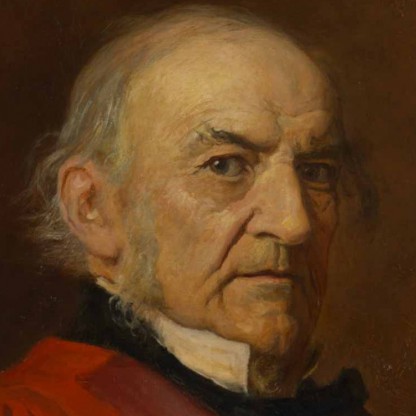

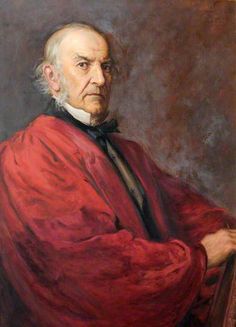

William Ewart Gladstone, a prominent political figure in British history, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in the year 2025. Renowned for his long and influential career, Gladstone served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on four separate occasions during the 19th century. He was deeply involved in political and economic reforms, advocating for issues such as free trade and Irish Home Rule. Throughout his life, Gladstone accumulated wealth through various means, including his successful law practice and astute investments. Despite being an esteemed statesman, he pursued a modest lifestyle, emphasizing public service over personal fortune.

With reference to rumours which I believe were at one time afloat, though I know not with what degree of currency: and also with reference to the times when I shall not be here to answer for myself, I desire to record my solemn declaration and assurance, as in the sight of God and before His Judgement Seat, that at no period of my life have I been guilty of the act which is known as that of infidelity to the marriage bed.

Although born and brought up in Liverpool, william Gladstone was of purely Scottish ancestry. His grandfather Thomas Gladstones (1732–1762) was a prominent merchant from Leith, and his maternal grandfather, Andrew Robertson, was Provost of Dingwall and a Sheriff-Substitute of Ross-shire. His biographer John Morley described him as: "a highlander in the custody of a lowlander," and an adversary as: "an ardent Italian in the custody of a Scotsman." One of his earliest childhood memories was being made to stand on a table and say "Ladies and gentlemen" to the assembled audience, probably at a gathering to promote the election of George Canning as MP for Liverpool in 1812. In 1814, young "Willy" visited Scotland for the first time, as he and his brother John travelled with their father to Edinburgh, Biggar and Dingwall to visit their relatives. Willy and his brother were both made freemen of the burgh of Dingwall. In 1815, Gladstone also travelled to London and Cambridge for the first time with his parents. Whilst in London, he attended a Service of thanksgiving with his family at St Paul's Cathedral following the Battle of Waterloo, where he saw the Prince Regent.

Born in 1809 in Liverpool, at 62 Rodney Street, william Ewart Gladstone was the fourth son of the merchant John Gladstones, and his second wife, Anne MacKenzie Robertson. In 1835, the family name was changed from Gladstones to Gladstone by royal licence. His father was made a baronet, of Fasque and Balfour, in 1846.

William Gladstone was educated from 1816-1821 at a preparatory school at the vicarage of St. Thomas' Church at Seaforth, close to his family's residence, Seaforth House. In 1821, william followed in the footsteps of his elder brothers and attended Eton College before matriculating in 1828 at Christ Church, Oxford, where he read Classics and Mathematics, although he had no great interest in the latter subject. In December 1831, he achieved the double first-class degree he had long desired. Gladstone served as President of the Oxford Union, where he developed a reputation as an orator, which followed him into the House of Commons. At university, Gladstone was a Tory and denounced Whig proposals for parliamentary reform.

Following the success of his double first, william travelled with his brother John on a Grand Tour of Europe, visiting Belgium, France, Germany and Italy. Upon his return to England, william was elected to Parliament in 1832 as a Tory Member of Parliament (MP) for Newark, partly through the influence of the local patron, the Duke of Newcastle. Although Gladstone entered Lincoln's Inn in 1833, with intentions of becoming a barrister, by 1839 he had requested that his name should be removed from the list because he no longer intended to be called to the Bar.

The following year, having met her in 1834 at the London home of Old Etonian friend and then fellow-Conservative MP James Milnes Gaskell, he married Catherine Glynne, to whom he remained married until his death 59 years later. They had eight children together:

Gladstone's early attempts to find a wife proved unsuccessful, with his being rejected by Caroline Eliza Farquhar (daughter of Sir Thomas Harvie Farquhar, 2nd Baronet) in 1835, and by Lady Frances Harriet Douglas (daughter of George Douglas, 17th Earl of Morton) in 1837. Gladstone published his first book, The State in its Relations with the Church, in 1838, in which he argued that the goal of the state should be to promote and defend the interests of the Church of England.

Gladstone's intensely religious mother was an evangelical of Scottish Episcopal origins, and his father joined the Church of England, having been a Presbyterian when he first settled in Liverpool. As a boy william was baptised into the Church of England. He rejected a call to enter the ministry, and on this his conscience always tormented him. In compensation he aligned his politics with the evangelical faith in which he fervently believed. In 1838 Gladstone nearly ruined his career when he tried to force a religious mission upon the Conservative Party. His book The State in its Relations with the Church argued that England had neglected its great duty to the Church of England. He announced that since that church possessed a monopoly of religious truth, nonconformists and Roman Catholics ought to be excluded from all government positions. The Historian Thomas Babington Macaulay and other critics ridiculed his weak arguments and tore them to shreds. Sir Robert Peel, Gladstone's chief, was outraged because this would upset the delicate political issue of Catholic Emancipation and anger the Nonconformists. Since Peel greatly admired his protégé, he redirected his focus from theology to Finance.

The opium trade faced intense opposition from Gladstone. Gladstone called it "most infamous and atrocious" referring to the opium trade between China and British India in particular. Gladstone was fiercely against both of the Opium Wars Britain waged in China, in the First Opium War initiated in 1840 and the Second Opium War initiated in 1857, denouncing British violence against Chinese, and was ardently opposed to the British trade of opium in China. Gladstone lambasted it as "Palmerston's Opium War" and said that he felt "in dread of the judgements of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China" in May 1840. A famous speech was made by Gladstone in Parliament against the First Opium War. Gladstone criticised it as "a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace." His hostility to opium stemmed from the effects of opium upon his sister Helen. Due to the First Opium war brought on by Palmerston, there was initial reluctance to join the government of Peel on the part of Gladstone before 1841.

Gladstone was re-elected in 1841. In September 1842 he lost the forefinger of his left hand in an accident while reloading a gun; thereafter he wore a glove or finger sheath (stall). In the second ministry of Robert Peel he served as President of the Board of Trade (1843–45).

Gladstone became concerned with the situation of "coal whippers". These were the men who worked on London docks, "whipping" in baskets from ships to barges or wharves all incoming coal from the sea. They were called up and relieved through public-houses and therefore a man could not get this job unless he possessed the favourable opinion of the publican, who looked upon most favourably those who drank. The man's name was written down and the "score" followed. Publicans issued employment solely on the capacity of the man to pay, and men often left the pub to work drunk. They spent their savings on drink to secure the favourable opinion of publicans and therefore further employment. Gladstone passed the Coal Vendors Act 1843 to set up a central office for employment. When this Act expired in 1856 a Select Committee was appointed by the Lords in 1857 to look into the question. Gladstone gave evidence to the Committee: "I approached the subject in the first instance as I think everyone in Parliament of necessity did, with the strongest possible prejudice against the proposal [to interfere]; but the facts stated were of so extraordinary and deplorable a character, that it was impossible to withhold attention from them. Then the question being whether legislative interference was required I was at length induced to look at a remedy of an extraordinary character as the only one I thought applicable to the case...it was a great innovation". Looking back in 1883, Gladstone wrote that "In principle, perhaps my Coalwhippers Act of 1843 was the most Socialistic measure of the last half century".

He resigned in 1845 over the Maynooth Grant issue, a matter of conscience for him. To improve relations with the Catholic Church, Peel's government proposed increasing the annual grant paid to Maynooth Seminary for training Catholic Priests in Ireland. Gladstone, who had previously argued in a book that a Protestant country should not pay money to other churches, nevertheless supported the increase in the Maynooth grant and voted for it in Commons – but resigned rather than face charges that he had compromised his principles to remain in office. After accepting Gladstone's resignation, Peel confessed to a friend, "I really have great difficulty sometimes in exactly comprehending what he means." Gladstone returned to Peel's government as Colonial Secretary in December 1845. "As such, he had to stand for re-election, but the strong protectionism of the Duke of Newcastle, his patron in Newark, meant that he could not stand there and no other seat was available. Throughout the corn law crisis of 1846, therefore, Gladstone was in the highly anomalous and possibly unique position of being a secretary of state without a seat in either house and thus unanswerable to parliament."

In 1850/51 Gladstone visited Naples for the benefit of his daughter Mary's eyesight. Giacomo Lacaita, legal adviser to the British embassy, was at the time imprisoned by the Neapolitan government, as were other political dissidents. Gladstone became concerned at the political situation in Naples and the arrest and imprisonment of Neapolitan liberals. In February 1851 Gladstone visited the prisons where they were held and in April and July he published two Letters to the Earl of Aberdeen against the Neapolitan government and responded to his critics in An Examination of the Official Reply of the Neapolitan Government in 1852. Gladstone's first letter described what he saw in Naples as "the negation of God erected into a system of government". Giustino Fortunato, prime minister of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, knew of the letters from Paolo Ruffo, Neapolitan ambassador in London, but he didn't inform the king Ferdinand II. After his unfulfilment, Fortunato was dismissed by the sovereign.

In 1852, following the appointment of Lord Aberdeen as Prime Minister, head of a coalition of Whigs and Peelites, Gladstone became Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Whig Sir Charles Wood and the Tory Disraeli had both been perceived to have failed in the office and so this provided Gladstone with a great political opportunity.

Gladstone inherited a deficit of nearly five million pounds, with income tax now set at 5d (fivepence). Like Peel, Gladstone dismissed the idea of borrowing to cover the deficit. Gladstone argued that "In time of peace nothing but dire necessity should induce us to borrow". Most of the money needed was acquired through raising the income tax to 9d. Usually not more than two-thirds of a tax imposed could be collected in a financial year so Gladstone therefore imposed the extra four pence at a rate of 8d. during the first half of the year so that he could obtain the additional revenue in one year. Gladstone's dividing line set up in 1853 had been abolished in 1858 but Gladstone revived it, with lower incomes to pay 6½d. instead of 9d. For the first half of the year the lower incomes paid 8d. and the higher incomes paid 13d. in income tax.

Britain entered the Crimean War in February 1854, and Gladstone introduced his second budget on 6 March. Gladstone had to increase expenditure on the military and a vote of credit of £1,250,000 was taken to send a force of 25,000 to the East. The deficit for the year would be £2,840,000 (estimated revenue £56,680,000; estimated expenditure £59,420,000). Gladstone refused to borrow the money needed to rectify this deficit and instead increased income tax by half, from sevenpence to tenpence-halfpenny in the pound (From ≈2.92% to ≈4.38%). He proclaimed that "the expenses of a war are the moral check which it has pleased the Almighty to impose on the ambition and the lust of conquest that are inherent in so many nations". By May £6,870,000 was needed to Finance the war and introducing another budget on 8 May, Gladstone raised income tax from tenpence halfpenny to fourteen pence in the pound to raise £3,250,000. Spirits, malt, and sugar were taxed to raise the rest of the money needed.

He served until 1855, a few weeks into Lord Palmerston's first premiership, and resigned along with the rest of the Peelites after a motion was passed to appoint a committee of inquiry into the conduct of the war.

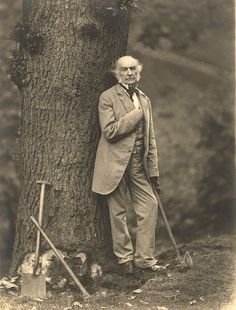

In 1858, Gladstone took up the hobby of tree felling, mostly of oak trees, an exercise he continued with enthusiasm until he was 81 in 1891. Eventually, he became notorious for this activity, prompting Lord Randolph Churchill to observe: "For the purposes of recreation he has selected the felling of trees; and we may usefully remark that his amusements, like his politics, are essentially destructive. Every afternoon the whole world is invited to assist at the crashing fall of some beech or elm or oak. The forest laments in order that Mr Gladstone may perspire." Less noticed at the time was his practice of replacing the trees felled by planting new saplings. Gladstone was a lifelong bibliophile; it has been suggested that in his lifetime, he read around 20,000 books, and eventually owned a library of over 32,000.

When Gladstone first joined Palmerston's government in 1859, he had opposed further electoral reform, but he changed his position during Palmerston's last premiership, and by 1865 he was firmly in favour of enfranchising the working classes in towns; the policy caused friction with Palmerston, who strongly opposed enfranchisement. At the beginning of each session, Gladstone would passionately urge the Cabinet to adopt new policies, while Palmerston would fixedly stare at a paper before him. At a lull in Gladstone's speech, Palmerston would smile, rap the table with his knuckles, and interject pointedly, "Now, my Lords and gentlemen, let us go to business".

Gladstone steadily reduced Income tax over the course of his tenure as Chancellor. In 1861 the tax was reduced to ninepence (£0–0s–9d), in 1863 to sevenpence, in 1864 to fivepence and in 1865 to fourpence. Gladstone believed that government was extravagant and wasteful with taxpayers' money and so sought to let money "fructify in the pockets of the people" by keeping taxation levels down through "peace and retrenchment". In 1859 he wrote to his brother, who was a member of the Financial Reform Association at Liverpool: "Economy is the first and great article (economy such as I understand it) in my financial creed. The controversy between direct and indirect taxation holds a minor, though important place". He wrote to his wife on 14 January 1860: "I am certain, from experience, of the immense advantage of strict account-keeping in early life. It is just like learning the grammar then, which when once learned need not be referred to afterwards".

As Chancellor, Gladstone made a speech at Newcastle on 7 October 1862 in which he supported the independence of the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War, claiming that Jefferson Davis had "made a nation". He did not consider slavery a problem; when Gladstone was first elected to Parliament his father owned over two and a half thousand slaves, and the young man helped his father to obtain full payment for them. Great Britain was officially neutral at the time. Gladstone later regretted the Newcastle speech.

In May 1864 Gladstone said that he saw no reason in principle why all mentally able men could not be enfranchised, but admitted that this would only come about once the working classes themselves showed more interest in the subject. Queen Victoria was not pleased with this statement, and an outraged Palmerston considered it seditious incitement to agitation.

Gladstone's support for electoral reform and disestablishment of the (Anglican) Church of Ireland alienated him from constituents in his Oxford University seat, and he lost it in the 1865 general election. A month later, however, he stood as a candidate in South Lancashire, where he was elected third MP (South Lancashire at this time elected three MPs). Palmerston campaigned for Gladstone in Oxford because he believed that his constituents would keep him "partially muzzled"; many Oxford graduates were Anglican clergymen at that time. A victorious Gladstone told his new constituency, "At last, my friends, I am come among you; and I am come—to use an expression which has become very famous and is not likely to be forgotten—I am come 'unmuzzled'."

Lord Russell retired in 1867 and Gladstone became leader of the Liberal Party. In 1868 the Irish Church Resolutions was proposed as a measure to reunite the Liberal Party in government (on the issue of disestablishment of the Church of Ireland – this would be done during Gladstone's First Government in 1869 and meant that Irish Roman Catholics did not need to pay their tithes to the Anglican Church of Ireland). When it was passed Disraeli took the hint and called a General Election.

Gladstone's proposals went some way to meet working-class demands, such as the realisation of the free breakfast table through repealing duties on tea and sugar, and reform of local taxation which was increasing for the poorer ratepayers. According to the working-class financial reformer Thomas Briggs, writing in the trade unionist newspaper The Bee-Hive, the manifesto relied on "a much higher authority than Mr. Gladstone...viz., the late Richard Cobden". The dissolution itself was reported in The Times on 24 January on 30 January, the names of the first fourteen MPs for uncontested seats were published; by 9 February a Conservative victory was apparent. In contrast to 1868 and 1880 when the Liberal campaign lasted several months, only three weeks separated the news of the dissolution and the election. The working-class newspapers were so taken by surprise they had little time to express an opinion on Gladstone's manifesto before the election was over. Unlike the efforts of the Conservatives, the organisation of the Liberal Party had declined since 1868 and they had also failed to retain Liberal voters on the electoral register. George Howell wrote to Gladstone on 12 February: "There is one lesson to be learned from this Election, that is Organization. ... We have lost not by a change of sentiment so much as by want of organised power". The Liberals received a majority of the vote in each of the constituent countries of the United Kingdom and 189,000 more votes nationally than the Conservatives. However, they obtained a minority of seats in the House of Commons.

He instituted abolition of the sale of commissions in the army: he also instituted the Cardwell Reforms in 1869 that made peacetime flogging illegal. As well as court reorganisation: he secured passage of the Ballot Act for secret ballots, and the Licensing Act 1872. In 1873, his leadership led to the passage of laws restructuring the High Courts. In 1870, the Irish Land Act and Forster's Education Act. In 1871, he instituted the Universities Tests Act. In foreign affairs his over-riding aim was to promote peace and understanding, characterised by his settlement of the Alabama Claims in 1872 in favour of the Americans.

Gladstone's first premiership instituted reforms in the British Army, civil Service, and local government to cut restrictions on individual advancement. The Local Government Board Act 1871 put the supervision of the Poor Law under the Local Government Board (headed by G. J. Goschen) and Gladstone's "administration could claim spectacular success in enforcing a dramatic reduction in supposedly sentimental and unsystematic outdoor poor relief, and in making, in co-operation with the Charity Organization Society (1869), the most sustained attempt of the century to impose upon the working classes the Victorian values of providence, self-reliance, foresight, and self-discipline". Gladstone was associated with the Charity Organization Society's first annual report in 1870. Some leading Conservatives at this time were contemplating an alliance between the aristocracy and the working class against the capitalist class, an idea called the New Social Alliance. At a speech at Blackheath on 28 October 1871, he warned his constituents against these social reformers:

In the wake of Benjamin Disraeli's victory, Gladstone retired from the leadership of the Liberal party, although he retained his seat in the House. In November 1874, he published the pamphlet The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance, directed at the First Vatican Council's dogmatising Papal Infallibility in 1870, which had outraged him. Gladstone claimed that this decree had placed British Catholics in a dilemma over conflicts of loyalty to the Crown. He urged them to reject papal infallibility as they had opposed the Spanish Armada of 1588. The pamphlet sold 150,000 copies by the end of 1874. A second pamphlet followed in Feb 1875, a defence of the earlier pamphlet and a reply to his critics, entitled Vaticanism: an Answer to Reproofs and Replies. He described the Catholic Church as "an Asian monarchy: nothing but one giddy height of despotism, and one dead level of religious subservience". He further claimed that the Pope wanted to destroy the rule of law and replace it with arbitrary tyranny, and then to hide these "crimes against liberty beneath a suffocating cloud of incense".

A pamphlet he published in September 1876, Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East, attacked the Disraeli government for its indifference to the Ottoman Empire's violent repression of the Bulgarian April uprising. Gladstone made clear his hostility focused on the Turkish people, rather than on the Muslim religion. The Turks he said:

During the 1879 election campaign, called the Midlothian campaign, he rousingly denounced Disraeli's foreign policies during the ongoing Second Anglo-Afghan War in Afghanistan. (See Great Game). He saw the war as "great dishonour" and also criticised British conduct in the Zulu War. Gladstone also (on 29 November) condemned what he saw as the Conservative government's profligate spending:

Lord Acton wrote in 1880 that he considered Gladstone one "of the three greatest Liberals" (along with Edmund Burke and Lord Macaulay).

In 1881 he established the Irish Coercion Act, which permitted the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland to detain people for as "long as was thought necessary", as there was rural disturbance in Ireland between landlords and tenants and Cavendish, the Irish Secretary, had been assassinated by Irish rebels in Dublin. He also passed the Second Land Act (the First, in 1870, had entitled Irish tenants, if evicted, to compensation for improvements which they had made on their property, but had had little effect) which gave Irish tenants the "3Fs" – fair rent, fixity of tenure and free sale. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1881.

On 11 July 1882, Gladstone ordered the bombardment of Alexandria, starting the Anglo-Egyptian War, which resulted in the occupation of Egypt. Gladstone's role in the decision to invade was described as relatively hands-off, and the ultimate responsibility was borne by certain members of his cabinet such as Lord Hartington, Secretary of State for India, Thomas Baring, 1st Earl of Northbrook, First Lord of the Admiralty, Hugh Childers, Secretary of State for War, and Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville, the Foreign Secretary. The reasons for this war are the subject of a historiographical debate. Some historians argue that the invasion was to protect the Suez Canal and to prevent anarchy in the wake of the Urabi Revolt and the riots in Alexandria in June 1882. Other historians argue that the invasion occurred to protect the interests of British Investors with assets in Egypt and also to boost the political popularity of the Liberal Party.

Gladstone extended the vote to agricultural labourers and others in the 1884 Reform Act, which gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs— adult male householders and £10 lodgers—and added six million to the total number of people who could vote in parliamentary elections. Parliamentary reform continued with the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885.

Gladstone espoused the policy of Home Rule in late 1885 (the "Hawarden Kite"), which resulted in the fall of Lord Salisbury's Government. Irish Nationalists, led by Charles Parnell's Irish Parliamentary Party, voted against the Tories on a land Bill. The Irish Nationalists held the balance of power in Parliament at this time. Gladstone's conversion to Home Rule convinced them to support the Liberal government using the 86 seats in Parliament they controlled. The main purpose of this administration was to deliver Ireland a reform which would give it a devolved assembly, similar to those now in place in Scotland and Wales. In 1886 Gladstone's party allied with Irish Nationalists to defeat Lord Salisbury's government. Gladstone regained his position as Prime Minister and combined the office with that of Lord Privy Seal. During this administration he first introduced his Home Rule Bill for Ireland. The issue split the Liberal Party (a breakaway group went on to create the Liberal Unionist party) and the bill was thrown out on the second reading, ending his government after only a few months and inaugurating another headed by Lord Salisbury.

Back in office in early 1886, Gladstone proposed home rule for Ireland but was defeated in the House of Commons. The resulting split in the Liberal Party helped keep them out of office – with one short break – for twenty years. Gladstone formed his last government in 1892, at the age of 82. The Second Home Rule Bill passed through the House of Commons but was defeated in the House of Lords in 1893. Gladstone left office in March 1894, aged 84, as both the oldest person to serve as Prime Minister and the only Prime Minister to have served four terms. He left parliament in 1895 and died three years later. Gladstone was known affectionately by his supporters as "The People's William" or the "G.O.M." ("Grand Old Man," or, according to his political rival Benjamin Disraeli, "God's Only Mistake"). He is consistently ranked as one of Britain's greatest prime ministers.

Gladstone supported the London dockers in their strike of 1889. After their victory he gave a speech at Hawarden on 23 September in which he said: "In the Common interests of humanity, this remarkable strike and the results of this strike, which have tended somewhat to strengthen the condition of labour in the face of capital, is the record of what we ought to regard as satisfactory, as a real social advance [that] tends to a fair principle of division of the fruits of industry". This speech has been described by Eugenio Biagini as having "no parallel in the rest of Europe except in the rhetoric of the toughest socialist leaders". Visitors at Hawarden in October were "shocked...by some rather wild language on the Dock labourers question". Gladstone was impressed with workers unconnected with the dockers' dispute who "intended to make Common cause" in the interests of justice.

On 23 October at Southport, Gladstone delivered a speech where he said that the right to combination, which in London was "innocent and lawful, in Ireland would be penal and...punished by imprisonment with hard labour". Gladstone believed that the right to combination used by British workers was in jeopardy when it could be denied to Irish workers. In October 1890 Gladstone at Midlothian claimed that competition between capital and labour, "where it has gone to sharp issues, where there have been strikes on one side and lock-outs on the other, I believe that in the main and as a general rule, the labouring man has been in the right".

Gladstone wrote to Herbert Spencer, who contributed the introduction to a collection of anti-socialist essays (A Plea for Liberty, 1891), that "I ask to make reserves, and of one passage, which will be easily guessed, I am unable even to perceive the relevancy. But speaking generally, I have read this masterly argument with warm admiration and with the earnest hope that it may attract all the attention which it so well deserves". The passage Gladstone alluded to was one where Spencer had spoken of "the behaviour of the so-called Liberal party".

The general election of 1892 resulted in a minority Liberal government with Gladstone as Prime Minister. The electoral address had promised Irish Home Rule and the disestablishment of the Scottish and Welsh Churches. In February 1893 he introduced the Second Home Rule Bill, which was passed in the Commons at second reading on 21 April by 43 votes and third reading on 1 September by 34 votes. The House of Lords defeated the bill by voting against by 419 votes to 41 on 8 September.

Conservative MP Colonel Howard Vincent questioned Gladstone in the Commons on what his government would do about unemployment on 1 September 1893. Gladstone replied:

Gladstone had his last audience with Queen Victoria on 28 February 1894 and chaired his last Cabinet on 1 March—the last of 556 he had chaired. On that day he gave his last speech to the House of Commons, saying that the government would withdraw opposition to the Lords' amendments to the Local Government Bill "under protest" and that it was "a controversy which, when once raised, must go forward to an issue". He resigned from the premiership on 2 March. The Queen did not ask Gladstone who should succeed him, but sent for Lord Rosebery (Gladstone would have advised on Lord Spencer). He retained his seat in the House of Commons until 1895. He was not offered a peerage, having earlier declined an earldom.

In 1895, at the age of 85, Gladstone bequeathed £40,000 (equivalent to approximately £4.24 million today) and much of his 32,000 volume library to found St Deiniol's Library in Hawarden, Wales. It had begun with just 5,000 items at his father's home Fasque, which were transferred to Hawarden for research in 1851.

On 8 January 1896, in conversation with L. A. Tollemache, Gladstone explained that: "I am not so much afraid of Democracy or of Science as of the love of money. This seems to me to be a growing evil. Also, there is a danger from the growth of that dreadful military spirit". On 13 January, Gladstone claimed he had strong Conservative instincts and that "In all matters of custom and tradition, even the Tories look upon me as the chief Conservative that is". On 15 January Gladstone wrote to James Bryce, describing himself as "a dead man, one fundamentally a Peel–Cobden man". In 1896, in his last noteworthy speech, he denounced Armenian massacres by Ottomans in a talk delivered at Liverpool. On 2 January 1897, Gladstone wrote to Francis Hirst on being unable to draft a preface to a book on liberalism: "I venture on assuring you that I regard the design formed by you and your friends with sincere interest, and in particular wish well to all the efforts you may make on behalf of individual freedom and independence as opposed to what is termed Collectivism".

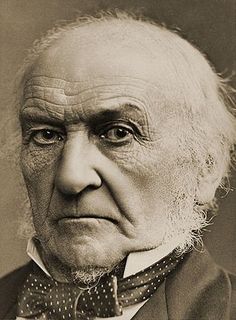

On the advice of his Doctor Samuel Habershon in the aftermath of an attack of facial neuralgia, Gladstone stayed at Cannes from the end of November 1897 to mid-February 1898. He gave an interview for The Daily Telegraph Gladstone then travelled to Bournemouth, where a swelling on his palate was diagnosed as cancer by the leading cancer surgeon Sir Thomas Smith on 18 March. On 22 March, he retired to Hawarden Castle. Despite being in pain he received visitors and quoted hymns, especially Cardinal Newman's "Praise to the Holiest in the Height".

Gladstone's burial in 1898 was commemorated in a poem by william McGonagall.

In 1909 the Liberal Chancellor David Lloyd George introduced his "People's Budget", the first budget which aimed to redistribute wealth. The Liberal statesman Lord Rosebery ridiculed it by asserting Gladstone would reject it, "Because in his eyes, and in my eyes, too, as his humble disciple, Liberalism and Liberty were cognate terms; they were twin-sisters."

David Lloyd George had written in 1913 that the Liberals were "carving the last few columns out of the Gladstonian quarry".

David Lloyd George said of Gladstone in 1915: "What a man he was! Head and shoulders above anyone else I have ever seen in the House of Commons. I did not like him much. He hated Nonconformists and Welsh Nonconformists in particular, and he had no real sympathy with the working-classes. But he was far and away the best Parliamentary speaker I have ever heard. He was not so good in exposition." Asquithian Liberals continued to advocate traditional Gladstonian policies of sound Finance, peaceful foreign relations and the better treatment of Ireland. They often compared Lloyd George unfavourably with Gladstone.

In 1927, during a court case over published claims that he had had improper relationships with some of these women, the jury unanimously found that the evidence "completely vindicated the high moral character of the late Mr. W. E. Gladstone".

Since 1937, Gladstone has been portrayed some 37 times in film and television.

Writing in 1944, the liberal Economist Friedrich Hayek said of the change in political attitudes that had occurred since the Great War: "Perhaps nothing shows this change more clearly than that, while there is no lack of sympathetic treatment of Bismarck in contemporary English literature, the name of Gladstone is rarely mentioned by the younger generation without a sneer over his Victorian morality and naive utopianism".

Gladstone visited the Earl of Meath at his Kilruddery Estate, and while in Bray, he visited the Anglican church there. Gladstone stated that 'such a fine steeple should not stand silent', and donated £50 (1/8th of the total cost) towards obtaining a new peal of bells there.

In the latter half of the twentieth-century Gladstone's economic policies came to be admired by Thatcherite Conservatives. Margaret Thatcher proclaimed in 1983: "We have a duty to make sure that every penny piece we raise in taxation is spent wisely and well. For it is our party which is dedicated to good housekeeping—indeed, I would not mind betting that if Mr Gladstone were alive today he would apply to join the Conservative Party". In 1996, she said: "The kind of Conservatism which he and I...favoured would be best described as 'liberal', in the old-fashioned sense. And I mean the liberalism of Mr Gladstone, not of the latter-day collectivists". Nigel Lawson, one of Thatcher's Chancellors, believed Gladstone to be the "greatest Chancellor of all time".

Gladstone is both the oldest person to form a government – aged 82 at his appointment – and the oldest person to occupy the Premiership – being 84 at his resignation. He resigned and handed over to Foreign Secretary, Lord Rosebery.

Gladstone and his wife appear as non-player characters in the 2015 video game Assassin's Creed: Syndicate. At the time the game is set, Gladstone is Chancellor of the Exchequer. In one in-game cutscene, he can be seen engaging in a heated argument with Disraeli.