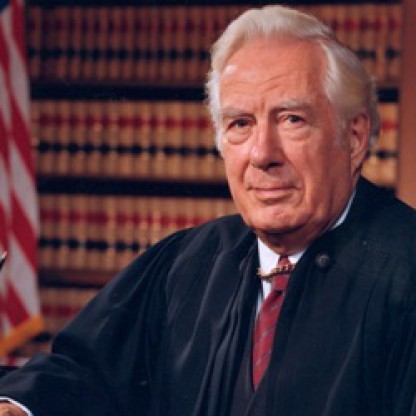

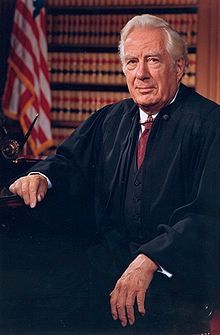

| Who is it? | Former Chief Justice of the United States |

| Birth Day | September 17, 1907 |

| Birth Place | Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States |

| Age | 113 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | June 25, 1995(1995-06-25) (aged 87)\nWashington, D.C., U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Harold Stephens |

| Succeeded by | Malcolm Wilkey |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Elvera Stromberg (m. 1933; d. 1994) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | University of Minnesota, Twin Cities (BA) St. Paul College of Law (LLB) |

Warren Earl Burger, the former Chief Justice of the United States, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2025. Serving as the Chief Justice from 1969 to 1986, Burger was known for his conservative views and commitment to upholding the Constitution. Despite his prestigious position, his net worth is relatively modest for someone of such influence and authority. Nonetheless, Warren Earl Burger's legacy continues to resonate in the United States, as he played a crucial role in shaping the country's legal landscape during his tenure.

I assume that no one will take issue with me when I say that these North European countries are as enlightened as the United States in the value they place on the individual and on human dignity. [Those countries] do not consider it necessary to use a device like our Fifth Amendment, under which an accused person may not be required to testify. They go swiftly, efficiently and directly to the question of whether the accused is guilty. No nation on earth goes to such lengths or takes such pains to provide safeguards as we do, once an accused person is called before the bar of justice and until his case is completed.

Warren Earl Burger was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, in 1907, and one of seven children. His parents, Katharine (née Schnittger) and Charles Joseph Burger, a traveling salesman and railroad cargo inspector, were of Austrian German descent. His grandfather, Joseph Burger, had emigrated from Tyrol, Austria and joined the Union Army when he was 12. Joseph Burger fought and was wounded in the Civil War, resulting in the loss of his right arm and was awarded the Medal of Honor at the age of 14. Joseph Burger by age 16 became the youngest Captain in the Union Army.

Burger grew up on the family farm near the edge of Saint Paul. He attended John A. Johnson High School, where he was President of the student council. He competed in hockey, football, track, and swimming. While in high school, he wrote articles on high school Sports for local newspapers. He graduated in 1925.

Burger attended night school at the University of Minnesota while selling insurance for Mutual Life Insurance. Afterward, he enrolled at St. Paul College of Law, (later became william Mitchell College of Law), receiving his degree magna cum laude in 1931. He took a job at the firm of Boyensen, Otis and Faricy, now known as Moore, Costello & Hart. In 1937, Burger served as the eighth President of the Saint Paul Jaycees. He also taught for twelve years at william Mitchell.

In this role, he first argued in front of the Supreme Court. The case involved John P. Peters, a Yale University professor who worked as a consultant to the government. He had been discharged from his position on loyalty grounds. Supreme Court cases are usually argued by the Solicitor General, but he disagreed with the government's position and refused to argue the case. Burger lost the case. Shortly after, Burger appeared in a case defending the United States against claims from the Texas City ship explosion disaster, successfully arguing that the Federal Tort Claims Act of 1947 did not allow a suit for negligence in policy making; the United States won the case (Dalehite, et al., vs. United States 346 U.S. 15 (1953)). In 1956, Eisenhower appointed him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. He remained on the Court of Appeals for thirteen years.

His political career began uneventfully, but he soon rose to national prominence. He supported Minnesota Governor Harold E. Stassen's unsuccessful pursuit of the Republican nomination for President in 1948. In 1952, at the Republican convention, he played a key role in Dwight D. Eisenhower's nomination by delivering the Minnesota delegation. After he was elected, President Eisenhower appointed Burger as the Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Civil Division of the Justice Department.

In 1968, Chief Justice Earl Warren announced his retirement after 15 years on the Court, effective on the confirmation of his successor. President Lyndon Johnson nominated sitting Associate Justice Abe Fortas to the position, but a Senate filibuster blocked his confirmation. With Johnson's term as President about to expire before another nominee could be considered, Warren remained in office.

Through speeches like this, Burger became known as a critic of Chief Justice Warren and an advocate of a literal, strict-constructionist reading of the U.S. Constitution. Nixon's agreement with these views, being expressed by a readily confirmable, sitting federal appellate judge, led to the appointment. The Senate confirmed Burger to succeed Warren, who in turn swore in the new chief on June 23, 1969. In his presidential campaign, Nixon had pledged to appoint a strict constructionist as Chief Justice.

When Burger was nominated for the Chief Justiceship, conservatives in the Nixon Administration expected that the Burger Court would rule markedly differently from the Warren Court and might, in fact, overturn controversial Warren Court era precedents. By the early 1970s, however, it became apparent that the Burger Court was not going to reverse the rulings of the Warren Court and in fact might extend some Warren Court doctrines.

The Court issued a unanimous ruling, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971) supporting busing to reduce de facto racial segregation in schools. In United States v. U.S. District Court (1972) the Burger Court issued another unanimous ruling against the Nixon Administration's Desire to invalidate the need for a search warrant and the requirements of the Fourth Amendment in cases of domestic surveillance. Then, only two weeks later in Furman v. Georgia (1972) the court, in a 5–4 decision, invalidated all death penalty laws then in force, although Burger dissented from the decision. In the most controversial ruling of his term, Roe v. Wade (1973), Burger voted with the majority to recognize a broad right to privacy that prohibited states from banning abortions. However, Burger abandoned Roe v. Wade by the time of Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

On July 24, 1974, Burger led the court in a unanimous decision in United States v. Nixon. This was President Nixon's attempt to keep several memos and tapes relating to the Watergate Affair private. As documented in Woodward and Armstrong's The Brethren and elsewhere, Burger's original feelings on the case were that Watergate was merely a political battle; he "didn't see what they did wrong." The actual final opinion was largely Justice Brennan's work, though each justice wrote at least a rough draft of a particular section. Burger was originally to vote in favor of Nixon, but tactically changed his vote in order to assign the opinion to himself, and to restrain the opinion's rhetoric. Burger's first draft of the opinion wrote that Executive Privilege could be invoked when it dealt with a "core function" of the Presidency, that in some cases the Executive could be supreme. However, the other justices in the Supreme Court were able to convince Burger to excise that language from the opinion —the judicial branch alone would have the power to determine whether something qualifies to be shielded under executive privilege.

On issues involving Criminal law and procedure, Burger remained reliably conservative. He joined the Court majority in voting to reinstate the death penalty in Gregg v. Georgia (1976), and, in 1983, he vigorously dissented from the Court's holding in the case of Solem v. Helm that a sentence of life imprisonment for issuing a fraudulent check in the amount of $100 constituted cruel and unusual punishment.

Burger also emphasized the maintenance of Checks and Balances between the branches of government. In the 1983 case of Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Chadha, he held, for the majority, that Congress could not reserve a legislative veto over executive branch actions.

As Chief Justice, Burger was instrumental in founding the Supreme Court Historical Society and was its first President. Burger is often cited as one of the foundational proponents of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), particularly in its ability to ameliorate an overloaded justice system. In a speech given in front of the American Bar Association, Justice Burger lamented the state of the justice system in 1984, "Our system is too costly, too painful, too destructive, too inefficient for a truly civilized people. To rely on the adversary process as the principal means of resolving conflicting claims is a mistake that must be corrected." The Warren E. Burger Federal Courthouse in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and the Warren E. Burger Library at his alma mater Mitchell Hamline School of Law (formerly the william Mitchell College of Law, and the St. Paul College of Law at the time of Burger's attendance) are named in his honor.

Burger retired on September 26, 1986, in part to lead the campaign to mark the 1987 bicentennial of the United States Constitution, at which time he commissioned the construction of the Constitution Bicentennial Monument (The National Monument to the U.S. Constitution). He had served longer than any other Chief Justice appointed in the 20th century. Despite his reputation for being imperious, he was beloved by the law clerks and judicial fellows who worked with him. In 1987, Princeton University's American Whig-Cliosophic Society awarded Burger the James Madison Award for Distinguished Public Service. In 1988, he was awarded the prestigious United States Military Academy's Sylvanus Thayer Award as well as the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In 1991 appearance on the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, Burger stated that the Second Amendment "has been the subject of one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word 'fraud,' on the American public by special interest groups."

He married Elvera Stromberg in 1933. They had two children, Wade Allen Burger and Margaret Elizabeth Burger. Elvera Burger died at their home in Washington, D.C., on May 30, 1994, at the age of 86.

Burger died in his sleep on June 25, 1995, from congestive heart failure at the age of 87, at Sibley Memorial hospital in Washington, D.C. He drafted his own one-page will. All of his papers were donated to the College of william and Mary, where he formerly served as Chancellor; however, they will not be open to the public until 2026.

Burger’s casket was displayed in the Great Hall of the U.S. Supreme Court Building. His remains are interred at Arlington National Cemetery.