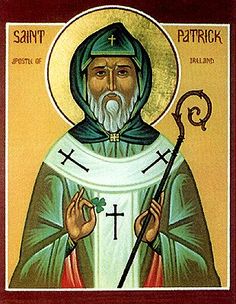

| Who is it? | Missionary |

| Died On | March 17, 0461 |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Anglican Communion Lutheran Churches |

| Major shrine | Armagh, Northern Ireland Glastonbury Abbey, England |

| Feast | 17 March (Saint Patrick's Day) |

| Patronage | Ireland, Nigeria, Montserrat, Archdiocese of New York, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark, Boston, Rolla, Missouri, Loíza, Puerto Rico, Murcia (Spain), Clann Giolla Phádraig, engineers, paralegals, Archdiocese of Melbourne; invoked against snakes, sins |

As of 2025, Saint Patrick's net worth is estimated to range between $100,000 and $1 million. Known as the patron saint of Ireland, Saint Patrick's legacy has expanded beyond religious significance, making him a cultural icon. While the exact details of his financial status may not be known, this estimation represents the value associated with his name, the celebration of St. Patrick's Day, and the widespread recognition of his influence. This wide range in net worth reflects the various sources of income related to this iconic figure, including tourism, merchandise, and cultural events. Ultimately, Saint Patrick's net worth symbolizes his enduring impact and the immense value placed on his legacy.

I saw a man coming, as it were from Ireland. His name was Victoricus, and he carried many letters, and he gave me one of them. I read the heading: "The Voice of the Irish". As I began the letter, I imagined in that moment that I heard the voice of those very people who were near the wood of Foclut, which is beside the western sea—and they cried out, as with one voice: "We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us."

Thomas Dinely, an English traveller in Ireland in 1681, remarked that "the Irish of all stations and condicõns were crosses in their hatts, some of pins, some of green ribbon." Jonathan Swift, writing to "Stella" of Saint Patrick's Day 1713, said "the Mall was so full of crosses that I thought all the world was Irish". In the 1740s, the badges pinned were multicoloured interlaced fabric. In the 1820s, they were only worn by children, with simple multicoloured daisy patterns. In the 1890s, they were almost extinct, and a simple green Greek cross inscribed in a circle of paper (similar to the Ballina crest pictured). The Irish Times in 1935 reported they were still sold in poorer parts of Dublin, but fewer than those of previous years "some in velvet or embroidered silk or poplin, with the gold paper cross entwined with shamrocks and ribbons".

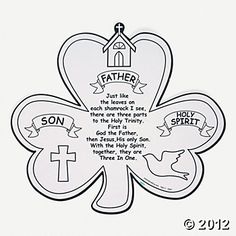

Legend credits Patrick with teaching the Irish about the doctrine of the Holy Trinity by showing people the shamrock, a three-leafed plant, using it to illustrate the Christian teaching of three persons in one God. This story first appears in writing in 1726, though it may be older. The shamrock has since become a central symbol for Saint Patrick's Day.

Saint Patrick's Saltire is a red saltire on a white field. It is used in the insignia of the Order of Saint Patrick, established in 1783, and after the Acts of Union 1800 it was combined with the Saint George's Cross of England and the Saint Andrew's Cross of Scotland to form the Union Flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. A saltire was intermittently used as a symbol of Ireland from the seventeenth century, but without reference to Patrick.

The Irish annals for the fifth century date Patrick's arrival in Ireland at 432, but they were compiled in the mid 6th century at the earliest. The date 432 was probably chosen to minimise the contribution of Palladius, who was known to have been sent to Ireland in 431, and maximise that of Patrick. A variety of dates are given for his death. In 457 "the elder Patrick" (Irish: Patraic Sen) is said to have died: this may refer to the death of Palladius, who according to the Book of Armagh was also called Patrick. In 461/2 the annals say that "Here some record the repose of Patrick"; in 492/3 they record the death of "Patrick, the arch-apostle (or archbishop and apostle) of the Scoti", on 17 March, at the age of 120.

The absence of snakes in Ireland gave rise to the legend that they had all been banished by Patrick chasing them into the sea after they attacked him during a 40-day fast he was undertaking on top of a hill. This hagiographic theme draws on the Biblical account of the staff of the prophet Moses. In Exodus 7:8–7:13, Moses and Aaron use their staffs in their struggle with Pharaoh's sorcerers, the staffs of each side turning into snakes. Aaron's snake-staff prevails by consuming the other snakes.

An early document which is silent concerning Patrick is the letter of Columbanus to Pope Boniface IV of about 613. Columbanus writes that Ireland's Christianity "was first handed to us by you, the successors of the holy apostles", apparently referring to Palladius only, and ignoring Patrick. Writing on the Easter controversy in 632 or 633, Cummian—it is uncertain whether this is Cumméne Fota, associated with Clonfert, or Cumméne Find—does refer to Patrick, calling him "our papa", that is, pope or primate.