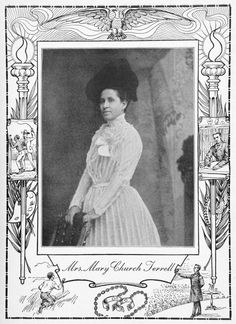

| Who is it? | Civil Rights Activist |

| Birth Day | September 23, 1863 |

| Birth Place | Memphis, United States |

| Age | 156 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | July 24, 1954(1954-07-24) (aged 90)\nAnnapolis, Maryland, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Other names | Euphemia Kirk |

| Occupation | Civil rights activist |

| Known for | One of the first African-American women to earn a college degree |

| Parent(s) | Robert Reed Church Louisa Ayers |

Mary Church Terrell, a prominent Civil Rights Activist in the United States, is estimated to have a net worth of $100K - $1M by 2025. Terrell was a pioneering African-American educator, writer, and advocate for social justice and gender equality. She played a significant role in advancing the civil rights movement by fighting for the rights of African Americans, especially women. Her tireless efforts and influential work made a lasting impact on society, leading to positive change and progress.

Mary Church Terrell was born Mary Church in 1863 in Memphis, Tennessee, to Robert Reed Church and Louisa Ayers, both freed slaves of mixed racial ancestry. Her parents were prominent members of the black elite of Memphis after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction Era. Her paternal grandmother was of Malagasy and white descent and her paternal grandfather was the Captain Charles B. Church, a white steamship owner and operator from Virginia who allowed his son Robert Church—Mary’s father—to keep the wages he earned as a steward on his ship. The younger Church continued to accumulate wealth by investing in real estate, and purchased his first property in Memphis in 1862. He made his fortune by buying property after the city was depopulated following the 1878 yellow fever epidemic. He is considered to be the first African-American millionaire in the South.

On October 18, 1891, in Memphis, Church married Robert Heberton Terrell, a Lawyer who became the first black municipal court judge in Washington, DC. The couple had met in Washington, DC, then they both worked at the M Street High School, where he became principal.

Combined with her achievements as a principal, the success of the League's educational initiatives led to Terrell's appointment to the District of Columbia Board of Education, 1895–1906. She was the first black woman in the United States to hold such a position. She was also an active member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. She was particularly concerned that the organization continue fighting for suffrage among black women. With Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, she formed the Federation of Afro-American Women.

In 1896, Terrell became the first President of the newly formed National Association of Colored Women (NACW), whose members established day nurseries and kindergartens, and helped orphans. That same year, she also founded the National Association of College Women, which later became the National Association of University Women (NAUW). The League started a training program and kindergarten, before these were included in the Washington, DC public schools.

In 1904, Terrell was invited to speak at the International Congress of Women, held in Berlin, Germany. She was the only black woman at the conference. She received an enthusiastic ovation when she honored the host nation by delivering her address in German. She delivered the speech in French, and concluded with the English version.

In 1909, Terrell was one of two black women (journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett was the other) invited to sign the “Call” and to attend the first organizational meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), becoming a founding member. In 1913–14, she helped organize the Delta Sigma Theta sorority. More than a quarter-century later, she helped write its creed that set up a code of conduct for black women.

Terrell worked actively in the women's suffrage movement, which pushed for enactment of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Active in the Republican Party, she was President of the Women's Republican League during Warren G. Harding's 1920 presidential campaign and the first election in which all American women were given the right to vote; Terrell reportedly said of the party: "Every right that has been bestowed upon blacks was initiated by the Republican Party." However, the Democrat-controlled Southern states from 1890 to 1908 had passed voter registration and election laws that effectively disfranchised most blacks. Those restrictions were not fully overturned until after congressional passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Terrell wrote an autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World (1940).

In 1950, she started what would be a successful fight to integrate eating places in the District of Columbia. In the 1890s the District of Columbia had formalized segregation as did states in the South. Before then, local integration laws dating to the 1870s had required all eating-place proprietors "to serve any respectable, well-behaved person regardless of color, or face a $1,000 fine and forfeiture of their license." In 1949, Terrell and colleagues Clark F. King, Essie Thompson, and Arthur F. Elmer entered the segregated Thompson Restaurant. When refused Service, they promptly filed a lawsuit. Attorney Ringgold Hart, representing Thompson, argued on April 1, 1950, that the District laws were unconstitutional and later won the case against restaurant segregation. In the three years pending a decision in District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., Terrell targeted other restaurants. Her tactics included boycotts, picketing, and sit-ins. Finally, on June 8, 1953, the court ruled that segregated eating places in Washington, DC, were unconstitutional.

She lived to see the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education, holding unconstitutional the racial segregation of public schools. Terrell died two months later at the age of 90, on July 24, 1954, in Anne Arundel General Hospital. It was the week before the NACW was to hold its annual meeting, that year at her town of Annapolis, Maryland.

Historians have generally emphasized Terrell's role as an activist—civil rights and women's rights—and community leader during the Progressive Era. She became cognizant of women's rights while at Oberlin, where she became familiar with Susan B. Anthony's activism. She also had a prosperous career as a Journalist (she identified as a writer). Using the pen name "Euphemia Kirk," she published in both the black and white press to promote the African American Women's Club Movement (Terrell, 1940). She wrote for a variety of newspapers "published either by or in the interest of colored people (Terrell, 1940, p. 222)," such as the A.M.E. Church Review of Philadelphia, PA; the Southern Workman of Hampton, VA; the Indianapolis Freeman; the Afro-American of Baltimore; the Washington Tribune; the Chicago Defender; the New York Age; the Voice of the Negro; the Women's World; and the Norfolk Journal and Guide (Terrell, 1940). She also contributed to the Washington Evening Star and the Washington Post (Terrell, 1940). She aligned the African-American Women's Club Movement with the broader struggle of black women and black people for equality. In 1892 she was elected as the first woman President of the prominent Washington DC black debate organization Bethel Literary and Historical Society

Mary Church, known to members of her family as "Mollie," and a brother were born during their father's first marriage, which ended in divorce. Their half-siblings, Robert, Jr. and Annette, were born to their father’s second wife, Anna Church, née Anna Wright, during his second marriage. Robert Church later married a third time.