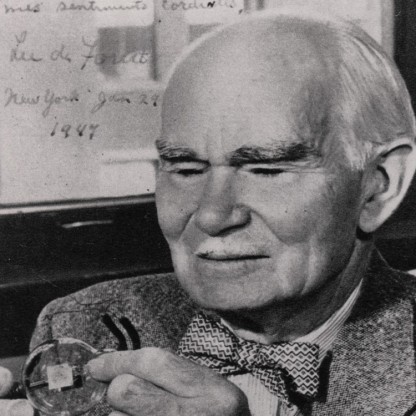

| Who is it? | Father of Radio |

| Birth Day | August 26, 1873 |

| Birth Place | Council Bluffs, Iowa, U.S., United States |

| Age | 146 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | June 30, 1961(1961-06-30) (aged 87)\nHollywood, California, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Virgo |

| Alma mater | Yale College (Sheffield Scientific School) |

| Occupation | Inventor |

| Known for | Three-electrode vacuum-tube (Audion), sound-on-film recording (Phonofilm) |

| Spouse(s) | Lucille Sheardown (m. 1906; div. 1906) Nora Stanton Blatch Barney (m. 1908; div. 1911) Mary Mayo (m. 1912; div. 1923) Marie Mosquini (m. 1930; his death 1961) |

| Parent(s) | Henry Swift DeForest Anna Robbins |

| Relatives | Calvert DeForest (grandnephew) |

| Awards | IEEE Medal of Honor (1922) Elliott Cresson Medal (1923) |

Lee de Forest, widely recognized as the Father of Radio in the United States, is projected to have a net worth of approximately $14 million by 2025. Throughout his illustrious career, de Forest made groundbreaking contributions to the development of radio technology and the broadcasting industry. With his invention of the Audion vacuum tube, he revolutionized long-distance radio communication, paving the way for the establishment of commercial radio networks. Given his impactful legacy and pioneering spirit, it comes as no surprise that de Forest's net worth is expected to reach such a significant figure.

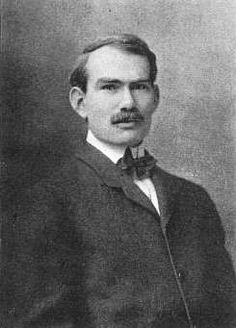

Lee de Forest was born in 1873 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, the son of Anna Margaret (née Robbins) and Henry Swift DeForest. He was a direct descendant of Jessé de Forest, the leader of a group of Walloon Huguenots who fled Europe in the 17th Century due to religious persecution.

De Forest's father was a Congregational Church minister who hoped his son would also become a pastor. In 1879 the elder de Forest became President of the American Missionary Association's Talladega College in Talladega, Alabama, a school "open to all of either sex, without regard to sect, race, or color", and which educated primarily African-Americans. Many of the local white citizens resented the school and its mission, and Lee spent most of his youth in Talladega isolated from the white community, with several close friends among the black children of the town.

De Forest prepared for college by attending Mount Hermon Boys' School in Mount Hermon, Massachusetts for two years, beginning in 1891. In 1893, he enrolled in a three-year course of studies at Yale University's Sheffield Scientific School in New Haven, Connecticut, on a $300 per year scholarship that had been established for relatives of David de Forest. Convinced that he was destined to become a famous—and rich—inventor, and perpetually short of funds, he sought to interest companies with a series of devices and puzzles he created, and expectantly submitted essays in prize competitions, all with little success.

Although raised in a strongly religious Protestant household, de Forest later became an agnostic. In his autobiography, he wrote that in the summer of 1894 there was an important shift in his beliefs: "Through that Freshman vacation at Yale I became more of a Philosopher than I have ever since. And thus, one by one, were my childhood's firm religious beliefs altered or reluctantly discarded."

De Forest was convinced there was a great Future in radiotelegraphic communication (then known as "wireless telegraphy"), but Italian Guglielmo Marconi, who received his first patent in 1896, was already making impressive progress in both Europe and the United States. One drawback to Marconi's approach was his use of a coherer as a receiver, which, while providing for permanent records, was also slow (after each received Morse code dot or dash, it had to be tapped to restore operation), insensitive, and not very reliable. De Forest was determined to devise a better system, including a self-restoring detector that could receive transmissions by ear, thus making it capable of receiving weaker signals and also allowing faster Morse code sending speeds.

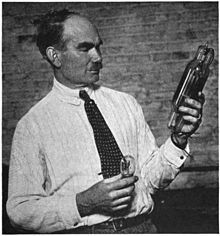

De Forest's most famous invention was the "grid Audion", which was the first successful three-element (triode) vacuum tube, and the first device which could amplify electrical signals. He traced its inspiration to 1900, when, experimenting with a spark-gap transmitter, he briefly thought that the flickering of a nearby gas flame might be in response to electromagnetic pulses. With further tests he soon determined that the cause of the flame fluctuations actually was due to air pressure changes produced by the loud sound of the spark. Still, he was intrigued by the idea that, properly configured, it might be possible to use a flame or something similar to detect radio signals.

De Forest soon felt that Smythe and Freeman were holding him back, so in the fall of 1901 he made the bold decision to go to New York to compete directly with Marconi in transmitting race results for the International Yacht races. Marconi had already made arrangements to provide reports for the Associated Press, which he had successfully done for the 1899 contest. De Forest contracted to do the same for the smaller Publishers' Press Association.

Despite this setback, de Forest remained in the New York City area, in order to raise interest in his ideas and capital to replace the small working companies that had been formed to promote his work thus far. In January 1902 he met a promoter, Abraham White, who would become de Forest's main sponsor for the next five years. White envisioned bold and expansive plans that enticed the Inventor — however, he was also dishonest and much of the new enterprise would be built on wild exaggeration and stock fraud. To back de Forest's efforts, White incorporated the American DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company, with himself as the company's President, and de Forest the Scientific Director. The company claimed as its goal the development of "world-wide wireless".

The original "responder" receiver (also known as the "goo anti-coherer") proved to be too crude to be commercialized, and de Forest struggled to develop a non-infringing device for receiving radio signals. In 1903, Reginald Fessenden demonstrated an electrolytic detector, and de Forest developed a variation, which he called the "spade detector", claiming it did not infringe on Fessenden's patents. Fessenden, and the U.S. courts, did not agree, and court injunctions enjoined American De Forest from using the device.

Meanwhile, White set in motion a series of highly visible promotions for American DeForest: "Wireless Auto No.1" was positioned on Wall Street to "send stock quotes" using an unmuffled spark transmitter to loudly draw the attention of potential Investors, in early 1904 two stations were established at Wei-hai-Wei on the Chinese mainland and aboard the Chinese steamer SS Haimun, which allowed war correspondent Captain Lionel James of The Times of London to report on the brewing Russo-Japanese War, and later that year a tower, with "DEFOREST" arrayed in Lights, was erected on the grounds of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis, Missouri, where the company won a gold medal for its radiotelegraph demonstrations. (Marconi withdrew from the Exposition when he learned de Forest would be there).

The company's most important early contract was the construction, in 1905–1906, of five high-powered radiotelegraph stations for the U.S. Navy, located in Panama, Pensacola and Key West, Florida, Guantanamo, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. It also installed shore stations along the Atlantic Coast and Great Lakes, and equipped shipboard stations. But the main focus was selling stock at ever more inflated prices, spurred by the construction of promotional inland stations. Most of these inland stations had no practical use and were abandoned once the local stock sales slowed.

After determining that an open flame was too susceptible to ambient air currents, de Forest investigated whether ionized gases, heated and enclosed in a partially evacuated glass tube, could be used instead. In 1905 to 1906 he developed various configurations of glass-tube devices, which he gave the general name of "Audions". The first Audions had only two electrodes, and on October 25, 1906, de Forest filed a patent for diode vacuum tube detector, that was granted U.S. patent number 841387 on January 15, 1907. Subsequently, a third "control" electrode was added, originally as a surrounding metal cylinder or a wire coiled around the outside of the glass tube. None of these initial designs worked particularly well. De Forest gave a presentation of his work to date to the October 26, 1906 New York meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, which was reprinted in two parts in late 1907 in the Scientific American Supplement. He was insistent that a small amount of residual gas was necessary for the tubes to operate properly. However, he also admitted that "I have arrived as yet at no completely satisfactory theory as to the exact means by which the high-frequency oscillations affect so markedly the behavior of an ionized gas."

In late 1906, de Forest made a breakthrough when he reconfigured the control electrode, changing it from outside the glass to a zig-zag wire inside the tube, positioned in the center between the cathode "filament" and the anode "plate" electrodes. He reportedly called the zig-zag control wire a "grid" due to its similarity to the "gridiron" lines on American football playing fields. Experiments conducted with his assistant, John V. L. Hogan, convinced him that he had discovered an important new radio detector, and he quickly prepared a patent application which was filed on January 29, 1907, and received U.S. patent number 879,532 on February 18, 1908. Because the grid-control Audion was the only configuration to become commercially valuable, the earlier versions were forgotten, and the term "Audion" later became synonymous with just the grid type. It later also became known as the triode.

Because of its limited uses and the great variability in the quality of individual units, the grid Audion would be rarely used during the first half-decade after its invention. In 1908, John V. L. Hogan reported that "The Audion is capable of being developed into a really efficient detector, but in its present forms is quite unreliable and entirely too complex to be properly handled by the usual wireless operator."

In May 1910, the Radio Telephone Company and its subsidiaries were reorganized as the North American Wireless Corporation, but financial difficulties meant that the company's activities had nearly come to a halt. De Forest moved to San Francisco, California, and in early 1911 took a research job at the Federal Telegraph Company, which produced long-range radiotelegraph systems using high-powered Poulsen arcs.

The company set up a network of radiotelephone stations along the Atlantic coast and the Great Lakes, for coastal ship navigation. However, the installations proved unprofitable, and by 1911 the parent company and its subsidiaries were on the brink of bankruptcy.

U.S. patent law included a provision for challenging grants if another Inventor could prove prior discovery. With an eye to increasing the value of the patent portfolio that would be sold to Western Electric in 1917, beginning in 1915 de Forest filed a series of patent applications that largely copied Armstrong's claims, in the hopes of having the priority of the competing applications upheld by an interference hearing at the patent office. Based on a notebook entry recorded at the time, de Forest asserted that, while working on the cascade amplifier, he had stumbled on August 6, 1912 across the feedback principle, which was then used in the spring of 1913 to operate a low-powered transmitter for heterodyne reception of Federal Telegraph arc transmissions. However, there was also strong evidence that de Forest was unaware of the full significance of this discovery, as shown by his lack of follow-up and continuing misunderstanding of the physics involved. In particular, it appeared that he was unaware of the potential for further development until he became familiar with Armstrong's research. De Forest was not alone in the interference determination — the patent office identified four competing claimants for its hearings, consisting of Armstrong, de Forest, General Electric's Langmuir, and a German, Alexander Meissner, whose application would be seized by the Office of Alien Property Custodian during World War I.

After a delay of ten months, in July 1913 AT&T, through a third party who disguised his link to the telephone company, purchased the wire rights to seven Audion patents for $50,000. De Forest had hoped for a higher payment, but was again in bad financial shape and was unable to bargain for more. In 1915, AT&T used the innovation to conduct the first transcontinental telephone calls, in conjunction with the Panama-Pacific International Exposition at San Francisco.

Beginning in 1913 Armstrong prepared papers and gave demonstrations that comprehensively documented how to employ three-element vacuum tubes in circuits that amplified signals to stronger levels than previously thought possible, and that could also generate high-power oscillations usable for radio transmission. In late 1913 Armstrong applied for patents covering the regenerative circuit, and on October 6, 1914 U.S. patent 1,113,149 was issued for his discovery.

The Radio Telephone Company began selling "Oscillion" power tubes to amateurs, suitable for radio transmissions. The company wanted to keep a tight hold on the tube Business, and originally maintained a policy that Retailers had to require their customers to return a worn-out tube before they could get a replacement. This style of Business encouraged others to make and sell unlicensed vacuum tubes which did not impose a return policy. One of the boldest was Audio Tron Sales Company founded in 1915 by Elmer T. Cunningham of San Francisco, whose Audio Tron tubes cost less but were of equal or higher quality. The de Forest company sued Audio Tron Sales, eventually settling out of court.

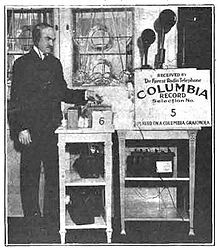

In the summer of 1915, the company received an Experimental license for station 2XG, located at its Highbridge laboratory. In late 1916, de Forest renewed the entertainment broadcasts he had suspended in 1910, now using the superior capabilities of vacuum-tube equipment. 2XG's debut program aired on October 26, 1916, as part of an arrangement with the Columbia Graphophone Company to promote its recordings, which included "announcing the title and 'Columbia Gramophone [sic] Company' with each playing". Beginning November 1, the "Highbridge Station" offered a nightly schedule featuring the Columbia recordings.

With the entry of the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917, all civilian radio stations were ordered to shut down, so 2XG was silenced for the duration of the war. The ban on civilian stations was lifted on October 1, 1919, and 2XG soon renewed operation, with the Brunswick-Balke-Collender company now supplying the phonograph records. In early 1920, de Forest moved the station's transmitter from the Bronx to Manhattan, but did not have permission to do so, so district Radio Inspector Arthur Batcheller ordered the station off the air. De Forest's response was to return to San Francisco in March, taking 2XG's transmitter with him. A new station, 6XC, was established as "The California Theater station", which de Forest later stated was the "first radio-telephone station devoted solely" to broadcasting to the public.

Later that year a de Forest associate, Clarence "C.S." Thompson, established Radio News & Music, Inc., in order to lease de Forest radio transmitters to newspapers interested in setting up their own broadcasting stations. In August 1920, The Detroit News began operation of "The Detroit News Radiophone", initially with the callsign 8MK, which later became broadcasting station WWJ.

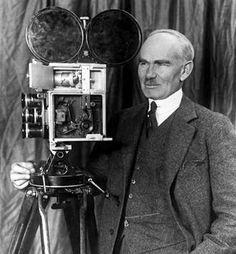

In 1921 de Forest ended most of his radio research in order to concentrate on developing an optical sound-on-film process called Phonofilm. In 1919 he filed the first patent for the new system, which improved upon earlier work by Finnish Inventor Eric Tigerstedt and the German partnership Tri-Ergon. Phonofilm recorded the electrical waveforms produced by a microphone photographically onto film, using parallel lines of variable shades of gray, an approach known as "variable density", in contrast to "variable area" systems used by processes such as RCA Photophone. When the movie film was projected, the recorded information was converted back into sound, in synchronization with the picture.

In November 1922, de Forest established the De Forest Phonofilm Company, located at 314 East 48th Street in New York City. But none of the Hollywood movie studios expressed interest in his invention, and because at this time these studios controlled all the major theater chains, this meant de Forest was limited to showing his experimental films in independent theaters (The Phonofilm Company would file for bankruptcy in September 1926.).

In April 1923, the De Forest Radio Telephone & Telegraph Company, which manufactured de Forest's Audions for commercial use, was sold to a group headed by Edward Jewett of Jewett-Paige Motors, which expanded the company's factory to cope with rising demand for radios. The sale also bought the services of de Forest, who was focusing his attention on newer innovations. De Forest's finances were badly hurt by the stock market crash of 1929, and research in mechanical television proved unprofitable. In 1934, he established a small shop to produce diathermy machines, and, in a 1942 interview, still hoped "to make at least one more great invention".

De Forest also worked with Freeman Harrison Owens and Theodore Case, using their work to perfect the Phonofilm system. However, de Forest had a falling out with both men. Due to de Forest's continuing misuse of Theodore Case's inventions and failure to publicly acknowledge Case's contributions, the Case Research Laboratory proceeded to build its own camera. That camera was used by Case and his colleague Earl Sponable to record President Coolidge on August 11, 1924, which was one of the films shown by de Forest and claimed by him to be the product of "his" inventions.

Believing that de Forest was more concerned with his own fame and recognition than he was with actually creating a workable system of sound film, and because of his continuing attempts to downplay the contributions of the Case Research Laboratory in the creation of Phonofilm, Case severed his ties with de Forest in the fall of 1925. Case successfully negotiated an agreement to use his patents with studio head william Fox, owner of Fox Film Corporation, who marketed the innovation as Fox Movietone. Warner Brothers introduced a competing method for sound film, the Vitaphone sound-on-disc process developed by Western Electric, with the August 6, 1926 release of the John Barrymore film Don Juan.

In 1927 and 1928, Hollywood expanded its use of sound-on-film systems, including Fox Movietone and RCA Photophone. Meanwhile, theater chain owner Isadore Schlesinger purchased the UK rights to Phonofilm and released short films of British music hall performers from September 1926 to May 1929. Almost 200 Phonofilm shorts were made, and many are preserved in the collections of the Library of Congress and the British Film Institute.

De Forest was a conservative Republican and fervent anti-communist and anti-fascist. In 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression, he voted for Franklin Roosevelt, but later came to resent him, calling Roosevelt America's "first Fascist president". In 1949, he "sent letters to all members of Congress urging them to vote against socialized Medicine, federally subsidized housing, and an excess profits tax". In 1952, he wrote to newly elected Vice President Richard Nixon, urging him to "prosecute with renewed vigor your valiant fight to put out Communism from every branch of our government". In December 1953, he cancelled his subscription to The Nation, accusing it of being "lousy with Treason, crawling with Communism."

This judicial ruling meant that Lee de Forest was now legally recognized in the United States as the Inventor of regeneration. However, much of the engineering community continued to consider Armstrong to be the actual developer, with de Forest viewed as someone who skillfully used the patent system to get credit for an invention to which he had barely contributed. Following the 1934 Supreme Court decision, Armstrong attempted to return his Institute of Radio Engineers (present-day Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) Medal of Honor, which had been awarded to him in 1917 "in recognition of his work and publications dealing with the action of the oscillating and non-oscillating audion", but the organization's board refused to let him, stating that it "strongly affirms the original award". The practical effect of de Forest's victory was that his company was free to sell products that used regeneration, for during the controversy, which became more a personal feud than a Business dispute, Armstrong tried to block the company from even being licensed to sell equipment under his patent.

De Forest was a vocal critic of many of the developments in the entertainment side of the radio industry. In 1940 he sent an open letter to the National Association of Broadcasters in which he demanded: "What have you done with my child, the radio broadcast? You have debased this child, dressed him in rags of ragtime, tatters of jive and boogie-woogie." That same year, de Forest and early TV Engineer Ulises Armand Sanabria presented the concept of a primitive unmanned combat air vehicle using a television camera and a jam-resistant radio control in a Popular Mechanics issue. In 1950 his autobiography, Father of Radio, was published, although it sold poorly.

The grid Audion, which de Forest called "my greatest invention", and the vacuum tubes developed from it, dominated the field of electronics for forty years, making possible long-distance telephone Service, radio broadcasting, television, and many other applications. It could also be used as an electronic switching element, and was later used in early digital electronics, including the first electronic computers, although the 1948 invention of the transistor would lead to microchips that eventually supplanted vacuum-tube Technology. For this reason de Forest has been called one of the founders of the "electronic age".

De Forest regularly responded to articles which he thought exaggerated Armstrong's contributions with animosity that continued even after Armstrong's 1954 suicide. Following the publication of Carl Dreher's "E. H. Armstrong, the Hero as Inventor" in the August 1956 Harper's magazine, de Forest wrote the author, describing Armstrong as "exceedingly arrogant, brow beating, even brutal...", and defending the Supreme Court decision in his favor.

De Forest was the guest Celebrity on the May 22, 1957, episode of the television show This Is Your Life, where he was introduced as "the father of radio and the grandfather of television". He suffered a severe heart attack in 1958, after which he remained mostly bedridden. He died in Hollywood on June 30, 1961, aged 87, and was interred in San Fernando Mission Cemetery in Los Angeles, California. De Forest died relatively poor, with just $1,250 in his bank account.

De Forest's archives were donated by his widow to the Perham Electronic Foundation, which in 1973 opened the Foothills Electronics Museum at Foothill College in Los Altos, California. In 1991 the college closed the museum, breaking its contract. The foundation won a lawsuit and was awarded $775,000. The holdings were placed in storage for twelve years, before being acquired in 2003 by History San José and put on display as The Perham Collection of Early Electronics.

With the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in 1898, de Forest enrolled in the Connecticut Volunteer Militia Battery as a bugler, but the war ended and he was mustered out without ever leaving the state. He then completed his studies at Yale's Sloane Physics Laboratory, earning a Doctorate in 1899 with a dissertation on the "Reflection of Hertzian Waves from the Ends of Parallel Wires", supervised by theoretical Physicist Willard Gibbs.

These broadcasts were also used to advertise "the products of the DeForest Radio Co., mostly the radio parts, with all the zeal of our catalogue and price list", until comments by Western Electric Engineers caused de Forest enough embarrassment to make him decide to eliminate the direct advertising. The station also made the first audio broadcast of election reports — in earlier elections, stations that broadcast results had used Morse code — providing news of the November 1916 Wilson-Hughes presidential election. The New York American installed a private wire and bulletins were sent out every hour. About 2000 listeners heard The Star-Spangled Banner and other anthems, songs, and hymns.