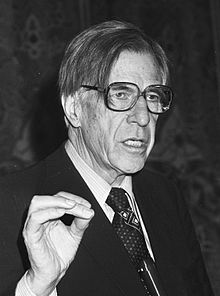

| Who is it? | Economist |

| Birth Day | October 15, 1908 |

| Birth Place | Iona Station, Canadian |

| Age | 112 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | April 29, 2006(2006-04-29) (aged 97)\nCambridge, Massachusetts, US |

| Birth Sign | Scorpio |

| Institution | Harvard University Princeton University University of California, Berkeley |

| School or tradition | Institutional economics |

| Alma mater | Ontario Agricultural College University of California, Berkeley |

| Influences | Thorstein Veblen, Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes, Michał Kalecki, Gardiner Means, Adolf A. Berle |

| Contributions | Countervailing power, Technostructure, Conventional wisdom |

| Awards | Lomonosov Gold Medal (1993) Officer of the Order of Canada (1997) Presidential Medal of Freedom (2000) |

John Kenneth Galbraith, a well-known Canadian economist, is estimated to have a net worth of $800,000 in 2025. Galbraith's vast expertise and contributions to the field of economics have earned him recognition and success throughout his career. Renowned for his influential theories and in-depth analysis, Galbraith's work has greatly influenced economic policies globally. With his insightful views and extensive experience, he has made a significant impact on the field of economics, solidifying his reputation as one of the foremost economists of our time.

[H]e had first gone to work in the nation's capital in 1934 as a 25-year-old, fresh out of graduate school and just about to join the Harvard faculty as a young instructor. He had returned to Washington in mid-1940, after Paris fell to the Germans, initially to help ready the nation for war. Eighteen months later, after Pearl Harbor, he was then appointed to oversee the wartime economy as "price czar," charged with preventing inflation and corrupt price-gouging from devastating the economy as it swelled to produce the weapons and materiel needed to guarantee victory against fascism. In this, he and his colleagues at the Office of Price Administration had been stunningly successful, guiding an economy that quadrupled in size in less than five years without fanning the inflation that had haunted World War I, or leaving behind an unbalanced post-war collapse of the kind that had done such grievous damage to Europe in the 1920s.

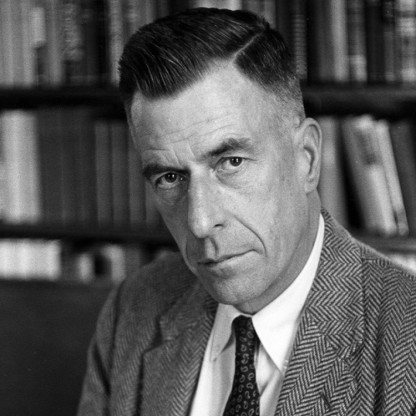

Galbraith was born on October 15, 1908, to Canadians of Scottish descent, Sarah Catherine (Kendall) and Archibald "Archie" Galbraith, in Iona Station, Ontario, Canada, and was raised in Dunwich Township, Ontario. He had three siblings: Alice, Catherine, and Archibald william (Bill). By the time he was a teenager, he had adopted the name Ken, and later disliked being called John. Galbraith grew to be a very tall man, attaining a height of 6 feet 9 inches (206 cm).

His early years were spent at a one-room school which is still standing, on Willy's Side Road. Later, he went to Dutton High School and St. Thomas High School. In 1931, Galbraith graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture from the Ontario Agricultural College, which was then an associate agricultural college of the University of Toronto. He majored in animal husbandry. He was awarded a Giannini Scholarship in Agricultural Economics (receiving $60 per month) that allowed him to travel to Berkeley, California, where he received Master of Science and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in agricultural economics from the University of California, Berkeley. Galbraith was taught economics by Professor George Martin Peterson, and together they wrote an economics paper titled "The Concept of Marginal Land" in 1932 that was published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics.

After graduation in 1934, he started to work as an instructor at Harvard University. Galbraith taught intermittently at Harvard in the period 1934 to 1939. From 1939 to 1940, he taught at Princeton University. In 1937, he became a citizen of the United States and was no longer a British subject. In the same year, he took a year-long fellowship at the University of Cambridge, England, where he was influenced by John Maynard Keynes. He then traveled in Europe for several months in 1938, attending an international economic conference and developing his ideas. His public Service started in the era of New Deal when he joined the United States Department of Agriculture. From 1943 until 1948, he served as an Editor of Fortune magazine. In 1949, he was appointed professor of economics at Harvard.

On September 17, 1937, Galbraith married Catherine Merriam Atwater, whom he met while she was a Radcliffe graduate student. Their marriage lasted for 68 years. The Galbraiths resided in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and had a summer home in Newfane, Vermont. They had four sons: J. Alan Galbraith is a partner in the Washington, DC, law firm Williams & Connolly; Douglas Galbraith died in childhood of leukemia; Peter W. Galbraith has been an American diplomat who served as Ambassador to Croatia and is a commentator on American foreign policy, particularly in the Balkans and the Middle East; James K. Galbraith is a progressive Economist at the University of Texas at Austin Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. The Galbraiths also have ten grandchildren.

On May 11, 1941, President Roosevelt signed the Executive Order 8734 which created the Office of Price Administration and Civilian Supply (OPACS). On August 28, 1941, an Executive Order 8875 transformed OPACS into the Office of Price Administration (OPA). After the US entered WWII in December 1941, OPA was tasked with rationing. The Emergency Price Control Act passed on January 30, 1942, legitimized the OPA as a separate federal agency. It merged OPA with two other agencies: Consumer Protection Division and Price Stabilization Division of the Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense. The council was referred to as the National Defense Advisory Commission (NDAC), and was created on May 29, 1940. NDAC emphasized voluntary and advisory methods in keeping prices low. Leon Henderson, the NDAC commissioner for price stabilization, became the head of OPACS and of OPA in 1941–1942. He oversaw a mandatory and vigorous price regulation that started in May 1942 after OPA introduced the General Maximum Price Regulation (GMPR). It was heavily criticized by the American Business community. In response, OPA mobilized the public on behalf of the new guidelines and said that it reduced the options for those who were seeking higher rents or prices. OPA had its own Enforcement Division, which documented the rising tide of violations: quarter million in 1943 and more than 300,000 during the next year.

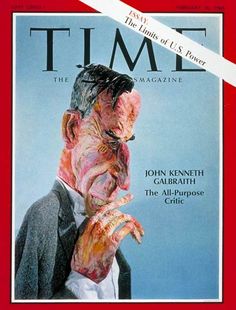

Opposition to the OPA came from conservatives in Congress and the Business community. It undercut Galbraith and he was forced out in May 1943, accused of "communistic tendencies". He was hired promptly by conservative Republican and a dominant figure in American media and publisher of Time and Fortune magazines, Henry Luce. Galbraith worked for Luce for five years and expounded Keynesianism to the American Business leadership. Luce allegedly said to President Kennedy, "I taught Galbraith how to write—and have regretted it ever since." Galbraith saw his role as educating the entire nation on how the economy worked, including the role of big corporations. He was combining his writing with numerous speeches to Business groups and local Democratic party meetings, as well as frequently testifying before Congress.

During the late stages of WWII in 1945, Galbraith was invited by Paul Nitze to serve as one of the Directors of the Strategic Bombing Survey, initiated by the Office of Strategic Services. It was designed to assess the results of the aerial bombardments of Nazi Germany. Galbraith contributed to the survey's unconventional conclusion about general ineffectiveness of strategic bombing in stopping the war production in Germany, which went up instead. The conclusion created a controversy, with Nitze siding with the Pentagon officials, who declared the opposite. Reluctant to modify the survey's results, Galbraith described the willingness of public servants and institutions to bend the truth to please the Pentagon as, the "Pentagonania syndrome".

John Kenneth Galbraith was one of the few people to receive both the Medal of Freedom and the Presidential Medal of Freedom; respectively in 1946 from President Truman and in 2000 from President Bill Clinton. He was a recipient of Lomonosov Gold Medal in 1993 for his contributions to science. He also was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1997 and, in 2001, awarded the Padma Vibhushan, India's second highest civilian award, for his contributions to strengthening ties between India and the United States.

Richard Parker, in his biography, John Kenneth Galbraith: His Life, His Economics, His Politics, characterizes Galbraith as a more complex thinker. Galbraith's primary purpose in Capitalism: The Concept of Countervailing Power (1952) was, ironically, to show that big Business was now necessary to the American economy to maintain the technological progress that drives economic growth. Galbraith knew that the "countervailing power", which included government regulation and collective bargaining, was necessary to balanced and efficient markets. In The New Industrial State (1967), Galbraith argued that the dominant American corporations had created a technostructure that closely controlled both consumer demand and market growth through advertising and marketing. While Galbraith defended government intervention, Parker notes that he also believed that government and big Business worked together to maintain stability.

His 1955 bestseller The Great Crash, 1929 describes the Wall Street meltdown of stock prices and how markets progressively become decoupled from reality in a speculative boom. The book is also a platform for Galbraith's humor and keen insights into human behavior when wealth is threatened. It has never been out of print.

In The Affluent Society (1958), which became a bestseller, Galbraith outlined his view that to become successful, post–World War II America should make large Investments in items such as highways and education, using funds from general taxation.

The New Industrial State not only provided Galbraith with another best-selling book, it also extended once again, the currency of institutionalist economic thought. The book also filled a very pressing need in the late 1960s. The conventional theory of monopoly power in economic life maintains that the monopolist will attempt to restrict supply in order to maintain price above its competitive level. The social cost of this monopoly power is a decrease in both allocative efficiency and the equity of income distribution. This conventional economic analysis of the role of monopoly power did not adequately address popular concern about the large corporation in the late 1960s. The growing concern focused on the role of the corporation in politics, the damage done to the natural environment by an unmitigated commitment to economic growth, and the perversion of advertising and other pecuniary aspects of culture. The New Industrial State gave a plausible explanation of the power structure involved in generating these problems and found a very receptive audience among the rising American counterculture and political Activists.

During his time as an adviser to President John F. Kennedy, Galbraith was appointed United States Ambassador to India from 1961 to 1963. His rapport with President Kennedy was such that he regularly bypassed the State Department and sent his diplomatic cables directly to the President. In India, he became a confidant of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and extensively advised the Indian government on economic matters. In 1966, when he was no longer ambassador, he told the United States Senate that one of the main causes of the 1965 Kashmir war was American military aid to Pakistan.

While in India, he helped establish one of the first computer science departments, at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh. Even after leaving office, Galbraith remained a friend and supporter of India. Because of his recommendation, First Lady of the United States Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy undertook her 1962 diplomatic missions in India and Pakistan.

The first edition of The Scotch was published in the UK under two alternative titles: as Made to Last and The Non-potable Scotch: A Memoir of the Clansmen in Canada. It was illustrated by Samuel H. Bryant. Galbraith's account of his boyhood environment in Elgin County in southern Ontario was added in 1963. He considered it his finest piece of writing.

In 1966, Galbraith was invited by the BBC to present the Reith Lectures, a series of radio broadcasts, which he titled The New Industrial State. Across six broadcasts, he explored the economics of production and the effect large corporations could have over the state.

In the print edition of The New Industrial State (1967), Galbraith expanded his analysis of the role of power in economic life, arguing that very few industries in the United States fit the model of perfect competition. A central concept of the book is the revised sequence. The 'conventional wisdom' in economic thought portrays economic life as a set of competitive markets governed, ultimately, by the decisions of sovereign consumers. In this original sequence, the control of the production process flows from consumers of commodities to the organizations that produce those commodities. In the revised sequence, this flow is reversed and businesses exercise control over consumers by advertising and related salesmanship activities.

A third related work was, Economics and the Public Purpose (1973), in which he expanded on these themes by discussing, among other issues, the subservient role of women in the unrewarded management of ever-greater consumption, and the role of the technostructure in the large firm in influencing perceptions of sound economic policy aims.

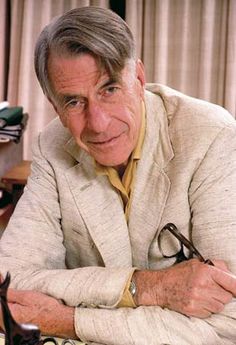

After his retirement from Harvard as the Paul M. Warburg Professor of Economics, Emeritus, he remained in the public spotlight by continuing to write 21 new books, as well as completing a script in 1977 for a major series on economics for PBS and BBC television—The Age of Uncertainty, broadcast in 38 countries.

Galbraith memoir, A Life in Our Times was published in 1981. It contains discussion of his thoughts, his life, and his times. In 2004, the publication of an authorized biography, John Kenneth Galbraith: His Life, His Politics, His Economics by a friend and fellow progressive Economist Richard Parker renewed interest in Galbraith's life journey and legacy.

In 1984, he visited the USSR, writing that the Soviet economy had made "great material progress" as, "in contrast to Western industrial economy," the USSR "makes full use of its manpower."

In 1985, the American Humanist Association named him the Humanist of the Year. The Association for Asian Studies (AAS) conferred its 1987 Award for Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies.

Paul Krugman downplayed Galbraith's stature as an academic Economist in 1994. In Peddling Prosperity, he places Galbraith as one among many "policy entrepreneurs"—either economists, or think tank Writers, left and right—who write solely for the public, as opposed to those who write for other academics, and who are, therefore, liable to make unwarranted diagnoses and offer over-simplistic answers to complex economic problems. Krugman asserts that Galbraith was never taken seriously by fellow academics, who instead viewed him as more of a "media personality". For Example, Krugman believes that Galbraith's work, The New Industrial State, is not considered to be "real economic theory", and that Economics in Perspective is "remarkably ill-informed".

In 1997 he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and in 2000 he was awarded the US Presidential Medal of Freedom. He also was awarded an honorary doctorate from Memorial University of Newfoundland at the fall convocation of 1999, another contribution to the impressive collection of approximately fifty academic honorary degrees bestowed on Galbraith. In 2000, he was awarded the Leontief Prize for his outstanding contribution to economic theory by the Global Development and Environment Institute. The library in his hometown Dutton, Ontario was renamed the John Kenneth Galbraith Reference Library in honor of his attachment to the library and his contributions to the new building.

An International Symposium to honor John Kenneth Galbraith, sponsored by the l'Université du Littoral Côte d'Opale, Dunkerque and the Institut de Gestion Sociale, Paris, France, was held in September 2004 in Paris.

On April 29, 2006, Galbraith died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, of natural causes at the age of 97, after a two-week stay in a hospital.

A special issue Commemorating John Kenneth Galbraith's Centenary of the Review of Political Economy was dedicated in 2008 to Galbraith's contribution to economics.

In 2010, he became the first Economist to have his works included in the Library of America series.

Galbraith proposed curbing the consumption of certain products through greater use of pigovian taxes and land value taxes, arguing that this could be more efficient than other forms of taxation, such as labor taxes. Galbraith's major proposal was a program he called "investment in men"—a large-scale, publicly funded education program aimed at empowering ordinary citizens.