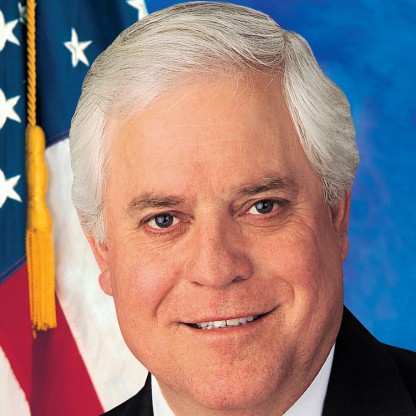

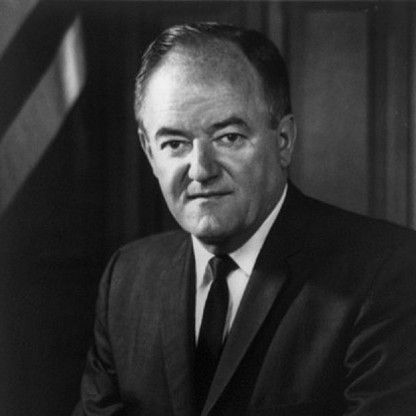

| Who is it? | 38th Vice President of the U.S |

| Birth Day | May 27, 1911 |

| Birth Place | Wallace, United States |

| Age | 109 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | January 13, 1978(1978-01-13) (aged 66)\nWaverly, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Gemini |

| President | James Eastland |

| Preceded by | Marvin Kline |

| Succeeded by | Eric G. Hoyer |

| Leader | Mike Mansfield |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Muriel Buck (m. 1936) |

| Children | 4, including Skip |

| Education | University of Minnesota, Twin Cities (BA) Capitol College of Pharmacy Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge (MA) |

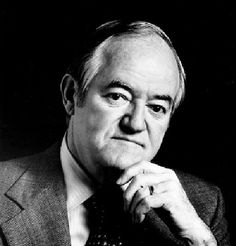

Hubert Humphrey, the renowned American politician and statesman, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in 2025. Humphrey is best known for his role as the 38th Vice President of the United States, serving from 1965 to 1969 during President Lyndon B. Johnson's administration. Throughout his career, Humphrey actively worked on various progressive and civil rights issues, leaving a lasting impact on American politics. Despite his influential position, his estimated net worth reflects a modest accumulation of wealth, suggesting a focus on public service rather than personal financial gains.

There were three bills of particular emotional importance to me: the Peace Corps, a disarmament agency, and the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. The President, knowing how I felt, asked me to introduce legislation for all three. I introduced the first Peace Corps bill in 1957. It did not meet with much enthusiasm. Some traditional diplomats quaked at the thought of thousands of young Americans scattered across their world. Many senators, including liberal ones, thought the idea was silly and unworkable. Now, with a young president urging its passage, it became possible and we pushed it rapidly through the Senate. It is fashionable now to suggest that Peace Corps Volunteers gained as much or more, from their experience as the countries they worked. That may be true, but it ought not demean their work. They touched many lives and made them better.

Humphrey was born in a room over his father's drugstore in Wallace, South Dakota. He was the son of Ragnild Kristine Sannes (1883–1973), a Norwegian immigrant, and Hubert Horatio Humphrey Sr. (1882–1949). Humphrey spent most of his youth in Doland, South Dakota, on the Dakota prairie; the town's population was about 600 when he lived there. His father was a licensed pharmacist who served as mayor and a town council member; he also served briefly in the South Dakota state legislature and was a South Dakota delegate to the 1944 and 1948 Democratic National Conventions. In the late 1920s, a severe economic downturn hit Doland; both of the town's banks closed and Humphrey's father struggled to keep his store open.

After his son graduated from Doland's high school, Hubert Sr. left Doland and opened a new drugstore in the larger town of Huron, South Dakota (population 11,000), where he hoped to improve his fortunes. Because of the family's financial struggles, Humphrey had to leave the University of Minnesota after just one year. He earned a pharmacist's license from the Capitol College of Pharmacy in Denver, Colorado (completing a two-year licensure program in just six months), and helped his father run his store from 1931 to 1937. Both father and son were innovative in finding ways to attract customers: "to supplement their Business, the Humphreys had become manufacturers...of patent medicines for both hogs and humans. A sign featuring a wooden pig was hung over the drugstore to tell the public about this unusual Service. Farmers got the message, and it was Humphrey's that became known as the farmer's drugstore." One biographer noted, "while Hubert Jr. minded the store and stirred the concoctions in the basement, Hubert Sr. went on the road selling 'Humphrey's BTV' (Body Tone Veterinary), a mineral supplement and dewormer for hogs, and 'Humphrey's Chest Oil' and 'Humphrey's Sniffles' for two-legged sufferers." Humphrey later wrote, "we made 'Humphrey's Sniffles', a substitute for Vick's Nose Drops. I felt ours were better. Vick's used mineral oil, which is not absorbent, and we used a vegetable-oil base, which was. I added benzocaine, a local anesthetic, so that even if the sniffles didn't get better, you felt it less." The various "Humphrey cures...worked well enough and constituted an important part of the family income...the farmers that bought the medicines were good customers." Over time Humphrey's Drug Store became a profitable enterprise and the family again prospered. While living in Huron, Humphrey regularly attended Huron's largest Methodist church and became the scoutmaster of the church's Boy Scout group, Troop 6. He "started basketball games in the church basement...although his scouts had no money for camp in 1931, Hubert found a way in the worst of that summer's dust-storm grit, grasshoppers, and depression to lead an overnight [outing]."

In 1934 Hubert began dating Muriel Buck, a bookkeeper and graduate of local Huron College. They were married from 1936 until Humphrey's death nearly 42 years later. They had four children: Hubert Humphrey III, Nancy, Robert, and Douglas. Unlike many prominent politicians, Humphrey never became a millionaire; one biographer noted, "For much of his life he was short of money to live on, and his relentless drive to attain the White House seemed at times like one long, losing struggle to raise enough campaign funds to get there."

Humphrey did not enjoy working as a pharmacist, and his dream remained to earn a doctorate in political science and become a college professor. His unhappiness was manifested in "stomach pains and fainting spells", though doctors could find nothing wrong with him. In August 1937, he told his father that he wanted to return to the University of Minnesota. Hubert Sr. tried to convince his son not to leave by offering him a full partnership in the store, but Hubert Jr. refused and told his father "how depressed I was, almost physically ill from the work, the dust storms, the conflict between my Desire to do something and be somebody and my loyalty to him...he replied "Hubert, if you aren't happy, then you ought to do something about it." Humphrey returned to the University of Minnesota in 1937 and earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1939. He was a member of Phi Delta Chi Fraternity. He also earned a master's degree from Louisiana State University in 1940, serving as an assistant instructor of political science there. One of his classmates was Russell B. Long, a Future U.S. Senator from Louisiana.

He then became an instructor and doctoral student at the University of Minnesota from 1940 to 1941 (joining the American Federation of Teachers), and was a supervisor for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Humphrey was a star on the university's debate team; one of his teammates was Future Minnesota Governor and US Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman. In the 1940 presidential campaign Humphrey and Future University of Minnesota President Malcolm Moos debated the merits of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Democratic nominee, and Wendell Willkie, the Republican nominee, on a Minneapolis radio station. Humphrey supported Roosevelt. Humphrey soon became active in Minneapolis politics, and as a result never finished his PhD.

Humphrey led various wartime government agencies and worked as a college instructor. In 1942, he was the state Director of new production training and reemployment and chief of the Minnesota war Service program. In 1943 he was the assistant Director of the War Manpower Commission. From 1943 to 1944, Humphrey was a professor of political science at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where he headed the university's recently created international debate department, which focused on the international politics of World War II and the creation of the United Nations. After leaving Macalester in the spring of 1944, Humphrey worked as a news commentator for a Minneapolis radio station until 1945.

In 1943, Humphrey made his first run for elective office, for Mayor of Minneapolis. He lost, but his poorly funded campaign still captured over 47% of the vote. In 1944, Humphrey was one of the key players in the merger of the Democratic and Farmer-Labor parties of Minnesota to form the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party (DFL). He also worked on President Roosevelt's 1944 reelection campaign. When Minnesota Communists tried to seize control of the new party in 1945, Humphrey became an engaged anticommunist and led the successful fight to oust the Communists from the DFL.

During the Second World War Humphrey tried three times to join the armed forces but failed. His first two attempts were to join the Navy, first as a commissioned officer and then as an enlisted man. He was rejected both times for color blindness. He then tried to enlist in the Army in December 1944 but failed the physical exam because of a double hernia, color blindness, and calcification of the lungs. Despite his attempts to join the military, one biographer would note that "all through his political life, Humphrey was dogged by the charge that he was a draft dodger".

After the war, he again ran for mayor of Minneapolis; this time, he won the election with 61% of the vote. He served as mayor from 1945 to 1948, winning reelection in 1947 by the largest margin in the city's history to that time. Humphrey gained national fame by becoming one of the founders of the liberal anticommunist Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), and he served as chairman from 1949 to 1950. He also reformed the Minneapolis police force. The city had been named the "anti-Semitism capital" of the country, and its small African-American population also faced discrimination. Humphrey's mayoralty is noted for his efforts to fight all forms of bigotry. He formed the Council on Human Relations and established a municipal version of the Fair Employment Practice Committee, making Minneapolis one of only a few cities in the United States to prohibit racial discrimination in the workforce. Humprey and his publicists were proud that the Council on Human Relations brought together individuals of varying ideologies. In 1960, Humphrey told Journalist Theodore H. White, "I was mayor once, in Minneapolis...a mayor is a fine job, it's the best job there is between being a governor and being the President."

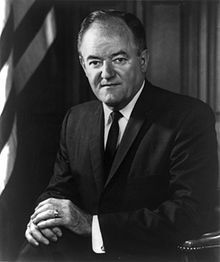

Initially, Humphrey's support of civil rights led to his being ostracized by Southern Democrats, who dominated Senate leadership positions and wanted to punish him for proposing the civil rights platform at the 1948 Convention. Senator Richard Russell Jr. of Georgia, a leader of Southern Democrats, once remarked to other Senators as Humphrey walked by, "Can you imagine the people of Minnesota sending that damn fool down here to represent them?" Humphrey refused to be intimidated and stood his ground; his integrity, passion and eloquence eventually earned him the respect of even most of the Southerners. The Southerners were also more inclined to accept Humphrey after he became a protégé of Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas. Humphrey became known for his advocacy of liberal causes (such as civil rights, arms control, a nuclear test ban, food stamps, and humanitarian foreign aid), and for his long and witty speeches. During the McCarthyist period (1950–54), Humphrey was accused of being "soft on communism" despite having been one of the founders of the anticommunist liberal organization Americans for Democratic Action, having been a staunch supporter of the Truman Administration's efforts to combat the growth of the Soviet Union, and having fought Communist political activities in Minnesota and elsewhere. In addition, Humphrey sponsored the clause in the McCarran Act of 1950 threatening concentration camps for "subversives", and in 1954 proposed to make mere membership in the Communist Party a felony, a proposal that failed. He was chairman of the Select Committee on Disarmament (84th and 85th Congresses). Although "Humphrey was an enthusiastic supporter of every U.S. war from 1938 to 1978", in February 1960 he introduced a bill to establish a National Peace Agency. With another former pharmacist, Representative Carl Durham, Humphrey cosponsored the Durham-Humphrey Amendment, which amended the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, defining two specific categories for medications, legend (prescription) and over-the-counter (OTC). As Democratic whip in the Senate in 1964, Humphrey was instrumental in the passage of the Civil Rights Act that year. He was a lead author of its text, alongside Republican Senate Republican Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois. Humphrey's consistently cheerful and upbeat demeanor, and his forceful advocacy of liberal causes, led him to be nicknamed "The Happy Warrior" by many of his Senate colleagues and political journalists.

Humphrey was elected to the United States Senate in 1948 on the DFL ticket, defeating James M. Shields in the DFL primary with 89% of the vote, and unseating incumbent Republican Joseph H. Ball in the general election with 60% of the vote. He took office on January 3, 1949, becoming the first Democrat elected senator from Minnesota since before the Civil War. Humphrey wrote that the victory heightened his sense of self, as he had beaten the odds of defeating a Republican with statewide support. Humphrey's father died that year, and Humphrey stopped using the "Jr." suffix on his name. He was reelected in 1954 and 1960. His colleagues selected him as majority whip in 1961, a position he held until he left the Senate on December 29, 1964, to assume the vice presidency. Humphrey served from the 81st to the 87th sessions of Congress, and in a portion of the 88th Congress.

On April 9, 1950, Humphrey said that President Truman would sign a $4 million housing bill and charge Republicans with having removed the bill's main middle-income benefits during Truman's tours of the Midwest and Northeast the following month.

In a January 1951 letter to President Truman, Humphrey wrote of the necessity of a commission akin to the Fair Employment Practices Commission that would be used to end discrimination in defense industries and predicted that establishing such a commission by executive order would be met with high approval by Americans.

On June 18, 1953, Humphrey introduced a resolution calling for the US to urge free elections in Germany in response to the anti-Communist riots in East Berlin.

While President John F. Kennedy is often credited for creating the Peace Corps, Humphrey introduced the first bill to create the Peace Corps in 1957—three years before Kennedy's University of Michigan speech. A trio of journalists wrote of Humphrey in 1969 that "few men in American politics have achieved so much of lasting significance. It was Humphrey, not Senator [Everett] Dirksen, who played the crucial part in the complex parliamentary games that were needed to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It was Humphrey, not John Kennedy, who first proposed the Peace Corps. The Food for Peace program was Humphrey's idea, and so was Medicare, passed sixteen years after he first proposed it. He worked for Federal aid to education from 1949, and for a nuclear-test ban treaty from 1956. These are the solid monuments of twenty years of effective work for liberal causes in the Senate." President Johnson once said that "Most Senators are minnows...Hubert Humphrey is among the whales." In his autobiography, The Education of a Public Man, Humphrey wrote:

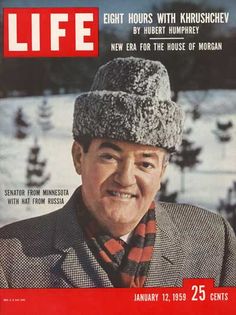

In December 1958, after receiving a message from Nikita Khrushchev during a visit to the Soviet Union, Humphrey returned insisting that the message was not negative toward America. In February 1959, Humphrey said Khrushchev's comments, in which he called Humphrey a purveyor of fairy tales, should have been ignored by American newspapers. In a September address to the National Stationary and Office Equipment Association, Humphrey called for further inspection of Khrushchev's "live and let live" doctrine and maintained the Cold War could be won by using American "weapons of peace".

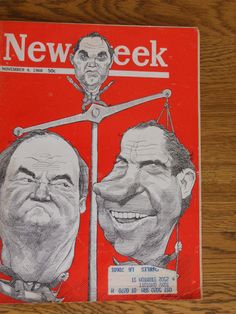

Humphrey's defeat in 1960 had a profound influence on his thinking; after the primaries he told friends that, as a relatively poor man in politics, he was unlikely to ever become President unless he served as Vice President first. Humphrey believed that only in this way could he attain the funds, nationwide organization, and visibility he would need to win the Democratic nomination. So as the 1964 presidential campaign began, Humphrey made clear his interest in becoming Lyndon Johnson's running mate. At the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Johnson kept the three likely vice-presidential candidates, Connecticut Senator Thomas Dodd, fellow Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy, and Humphrey, as well as the rest of the nation, in suspense before announcing his choice of Humphrey with much fanfare, praising his qualifications at considerable length before announcing his name.

On December 10, 1964, Humphrey met with President Johnson in the Oval Office, the latter charging the vice president-elect with "developing a publicity machine extraordinaire and of always wanting to get his name in the paper." Johnson showed Humphrey a George Reed memo with the allegation that the President would die within six months from an already acquired fatal heart disease. The same day, President Johnson announced Humphrey would have the position of giving assistance to governmental civil rights programs during a speech in Washington.

During a May 31, 1966 appearance at Huron College, Humphrey said the US should not expect "either friendship or gratitude" in helping poorer countries. At a September 22, 1966 Jamesburg, New Jersey Democratic Party fundraiser, Humphrey said the Vietnam War would be shortened if the US stayed firm and hasten the return of troops: "We are making a decision not only to defend Vietnam, we are defending the United States of America."

Humphrey began a European tour in late-March 1967 to mend frazzled relations. At the time of its beginning, Humphrey indicated that he was "ready to explain and ready to Listen." On April 2, 1967, Vice President Humphrey met with Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Harold Wilson. Ahead of the meeting, Humphrey said they would discuss multiple topics including the nuclear nonproliferation treaty, European events, Atlantic alliance strengthening, and "the situation in the far east". White House Press Secretary George Christian said five days later that he had received reports from Vice President Humphrey indicating his tour of the European countries was "very constructive" and said President Johnson was interested in the report as well. While Humphrey was in Florence, Italy on April 1, 1967, 23-year-old Giulio Stocchi threw eggs at the Vice President and missed, being seized by American Bodyguards who turned him into Italian officers. In Brussels, Belgium on April 9, demonstrators led by communists threw rotten eggs and fruits at Vice President Humphrey's car, also hitting several of his Bodyguards. In late-December 1967, Vice President Humphrey began touring Africa.

Many people saw Humphrey as Johnson's stand-in; he won major backing from the nation's labor unions and other Democratic groups that were troubled by young antiwar protesters and the social unrest around the nation. A group of British journalists wrote that Humphrey, despite his liberal record on civil rights and support for a nuclear test-ban treaty, "had turned into an arch-apologist for the war, who was given to trotting around Vietnam looking more than a little silly in olive-drab fatigues and a forage cap. The man whose name had been a by-word in the South for softness toward Negroes had taken to lecturing black groups...the wild-eyed reformer had become the natural champion of every conservative element in the Democratic Party." Humphrey entered the race too late to participate in the Democratic primaries and concentrated on winning delegates in non-primary states by gaining the support from Democratic officeholders who were elected delegates for the Democratic Convention. By June, McCarthy won in Oregon and Pennsylvania, while Kennedy had won in Indiana and Nebraska, though Humphrey was the front Runner as he led the delegate count. The California primary was crucial for Kennedy's campaign, as a McCarthy victory would've prevented Kennedy from reaching the amount of delegates required to secure the nomination. On June 4, 1968, Kennedy defeated McCarthy by less than 4% in the California primary. But the nation was shocked yet again when Senator Kennedy was assassinated after his victory speech at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California. After the assassination of Kennedy, Humphrey suspended his campaign for two weeks.

On February 11, 1969, Humphrey met privately with Mayor Richard J. Daley and denied ever being "at war" with Daley during a press conference later in the day. In March, Humphrey declined answering questions on the Johnson administration being either involved or privy to the cessation of bombing of the north in Vietnam during an interview on Issues and Answers. At a press conference on June 2, 1969, Humphrey backed Nixon's peace efforts, dismissing the notion that he was not seeking an end to the war. In early July, Humphrey traveled to Finland for a private visit. Later that month, Humphrey returned to Washington after visiting Europe, a week after McCarthy declared he would not seek reelection, Humphrey declining to comment amid speculation he intended to return to the Senate. During the fall, Humphrey arranged to meet with President Nixon through United States National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, Humphrey saying the day after the meeting that President Nixon had "expressed his appreciation on my attitude to his effort on Vietnam." On August 3, Humphrey said that Russia was buying time to develop ballistic missile warheads in order to catch up with the United States and that security was the "overriding concern" of the Soviet Union. Days later, Humphrey repudiated efforts against President Nixon's anti-ballistic missile system: "I have a feeling that they [opponents of the ABM] were off chasing rabbits when a tiger is loose." During October, Humphrey spoke before the AFL-CIO convention delegates, charging President Nixon's economic policies with "putting Americans out of work without slowing inflation." On October 10, Humphrey stated his support for Nixon's policies in Vietnam and that he believed "the worst thing that we can do is to try to undermine the efforts of the President." At a December 21 press conference, Humphrey said President Nixon was a participant in the "politics of polarization" and could not seek unity on one hand but have divisive agents on the other. On December 26, Humphrey responded to a claim from former President Johnson that Humphrey had been cost the election by his own call for a stop to North Vietnam bombing, saying he did what he "thought was right and responsible at Salt Lake City."

On November 4, 1970, shortly after being elected to the Senate, Humphrey stated his intention to take on the role of a "harmonizer" with the Democratic Party for the purpose of minimizing the possibility of potential presidential candidates within the party lambasting each other prior to deciding to run in the then-upcoming election, dismissing that he was an active candidate at that time. In December 1971, Humphrey made his second trip to New Jersey in under a month, talking with a plurality of county Leaders at the Robert Treat Hotel: "I told them I wanted their support. I said I'd rather work with them than against them."

L. Edward Purcell wrote that upon returning to the Senate, Humphrey found himself "again a lowly junior senator with no seniority" and that he resolved to create credibility in the eyes of liberals. On May 3, 1971, after the Americans for Democratic Action adopted a resolution demanding President Nixon's impeachment, Humphrey commented that they were acting "more out of emotion and passion than reason and prudent judgement" and that the request was irresponsible. On May 21, Humphrey said ending hunger and malnutrition in the US was "a moral obligation" during a speech to International Food Service Manufacturers Association members at the Conrad Hilton Hotel. In June, Humphrey delivered the commencement address at the University of Bridgeport and days later said that he believed Nixon was interested in seeing a peaceful end to the Vietnam War "as badly as any senator or anybody else." On July 14, while testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Arms Control, Humphrey proposed amending the defense procurement bill to place in escrow all funds for creation and usage of multiple‐missile warheads in the midst of continued arms limitations talks. Humphrey said members of the Nixon administration needed to remember "when they talk of a tough negotiating position, they are going to get a tough response." On September 6, Humphrey rebuked the Nixon administration's wage price freeze, saying it was based on trickle-down policies and advocating "percolate up" as a replacement, while speaking at a United Rubber Workers gathering. On October 26, Humphrey stated his support for removing barriers to voting registration and authorizing students to establish voting residences in their respective college communities, rebuking the refusal of United States Attorney General John N. Mitchell the previous month to take a role in shaping voter registration laws as applicable to new voters. On December 24, 1971, Humphrey accused the Nixon administration of turning its back on the impoverished in the rural parts of the United States, citing few implementations of the relief recommendations of the 1967 National Advisory Commission; in another statement he said only 3 of the 150 recommendations had been implemented. On December 27, Humphrey said the Nixon administration was responsible for an escalation of the Southeast Asia war and requested complete cessation of North Vietnam bombing while responding to antiwar protestors in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In 1972, Humphrey once again ran for the Democratic nomination for President, announcing his candidacy on January 10, 1972 during a twenty-minute speech in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At the time of the announcement, Humphrey said he was running on a platform of the removal of troops from Vietnam and a revitalization of the United States economy. He drew upon continuing support from organized labor and the African-American and Jewish communities, but remained unpopular with college students because of his association with the Vietnam War, even though he had altered his position in the years since his 1968 defeat. Humphrey initially planned to skip the primaries, as he had in 1968. Even after he revised this strategy he still stayed out of New Hampshire, a decision that allowed McGovern to emerge as the leading challenger to Muskie in that state. Humphrey did win some primaries, including those in Ohio, Indiana and Pennsylvania, but was defeated by McGovern in several others, including the crucial California primary. Humphrey also was out-organized by McGovern in caucus states and was trailing in delegates at the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida. His hopes rested on challenges to the credentials of some of the McGovern delegates. For Example, the Humphrey forces argued that the winner-take-all rule for the California primary violated procedural reforms intended to produce a better reflection of the popular vote, the reason that the Illinois delegation was bounced. The effort failed, as several votes on delegate credentials went McGovern's way, guaranteeing his victory.

In January 1973, Humphrey said the Nixon administration was plotting to eliminate a school milk program in the upcoming fiscal year budget during a telephone interview. On February 18, 1973, Humphrey said the Middle East could possibly usher in peace following the Vietnam War ending along with American troops withdrawing from Indochina during an appearance at the New York Hilton. In August 1973, Humphrey called on Nixon to schedule a meeting with nations exporting and importing foods as part of an effort to both create a worldwide policy on food and do away with food hoarding. After Nixon's dismissal of Archibald Cox, Humphrey said he found "the whole situation entirely depressing." Three days after Cox's dismissal, during a speech to the AFL-CIO convention on October 23, Humphrey declined to state his position on whether Nixon should be impeached, citing that his congressional position would likely cause him to have to play a role in determining Nixon's fate. On December 21, Humphrey disclosed his request of federal tax deductions of 199,153 USD for the donation of his vice presidential papers to the Minnesota State Historical Society.

In 1974, along with Rep. Augustus Hawkins of California, Humphrey authored the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act, the first attempt at full employment legislation. The original bill proposed to guarantee full employment to all citizens over 16 and set up a permanent system of public jobs to meet that goal. A watered-down version called the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act passed the House and Senate in 1978. It set the goal of 4 percent unemployment and 3 percent inflation and instructed the Federal Reserve Board to try to produce those goals when making policy decisions.

On May 5, 1975, Humphrey testified at the trial of his former campaign manager Jack L. Chestnut, admitting that as a candidate he sought the support the Associated Milk Producers, Inc. but at that time was not privy to the illegal contributions Chestnut was accused of taking from the organization.

Humphrey attended the November 17, 1976 meeting between President-elect Carter and Democratic congressional Leaders in which Carter sought out support for a proposal to have the president's power to reorganize the government reinstated with potential to be vetoed by Congress.

Humphrey ran for Majority Leader after the 1976 election but lost to Robert Byrd of West Virginia. The Senate honored Humphrey by creating the post of Deputy President pro tempore of the Senate for him. On August 16, 1977, Humphrey revealed he was suffering from terminal bladder cancer. On October 25 of that year, he addressed the Senate, and on November 3, Humphrey became the first person other than a member of the House or the President of the United States to address the House of Representatives in session. President Carter honored him by giving him command of Air Force One for his final trip to Washington on October 23. One of Humphrey's final speeches contained the lines "It was once said that the moral test of Government is how that Government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; and those who are in the shadows of life, the sick, the needy and the handicapped", which is sometimes described as the "liberals' mantra".

In 1978, Humphrey received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.

He was awarded posthumously the Congressional Gold Medal on June 13, 1979 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980.

He was honored by the United States Postal Service with a 52¢ Great Americans series (1980–2000) postage stamp.

Muriel Humphrey remarried in 1981 (to Max Brown) and took the name Muriel Humphrey Brown. She died in 1998 at the age of 86 and is interred next to Hubert Humphrey.

Humphrey and his running mate, Ed Muskie, who had not entered any of the 13 state primary elections, went on to win the Democratic nomination at the party convention in Chicago, Illinois even though 80 percent of the primary voters had been for anti-war candidates, the delegates had defeated the peace plank by 1,567¾ to 1,041¼. Unfortunately for Humphrey and his campaign, in Grant Park, just five miles south of International Amphitheater convention hall (closed 1999), and at other sites near downtown Chicago, there were gatherings and protests by the thousands of antiwar demonstrators, many of whom favored McCarthy, George McGovern, or other "anti-war" candidates. These protesters – most of them young college students – were attacked and beaten on live television by Chicago police, actions which merely amplified the growing feelings of unrest in the general public.

As Vice President, Humphrey was controversial for his complete and vocal loyalty to Johnson and the policies of the Johnson Administration, even as many of his liberal admirers opposed Johnson's policies with increasing fervor regarding the Vietnam War. Many of Humphrey's liberal friends and allies abandoned him because of his refusal to publicly criticize Johnson's Vietnam War policies. Humphrey's critics later learned that Johnson had threatened Humphrey – Johnson told Humphrey that if he publicly criticized his policy, he would destroy Humphrey's chances to become President by opposing his nomination at the next Democratic Convention. However, Humphrey's critics were vocal and persistent: even his nickname, "the Happy Warrior", was used against him. The nickname referred not to his military hawkishness, but rather to his crusading for social welfare and civil rights programs. After his narrow defeat in the 1968 presidential election, Humphrey wrote that "After four years as Vice-President ... I had lost some of my personal identity and personal forcefulness. ... I ought not to have let a man [Johnson] who was going to be a former President dictate my Future."