| Who is it? | Former French Prime Minister |

| Birth Day | September 28, 1841 |

| Birth Place | Mouilleron-en-Pareds, Vendee, French |

| Age | 178 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 24 November 1929(1929-11-24) (aged 88)\nParis, Seine, France |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| President | Armand Fallières |

| Preceded by | Pierre Marmottan |

| Succeeded by | Barthélemy Forest |

| Prime Minister | Ferdinand Sarrien |

| Constituency | Seine |

| Political party | Radical Republican (1871–1901) Radical-Socialist Party (1901–1920) |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Plummer (m. 1869; div. 1891) |

| Children | Michel |

| Alma mater | University of Nantes |

| Profession | Physician, journalist |

| Nickname(s) | Father of Victory The Tiger |

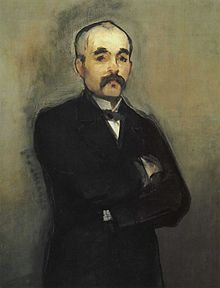

Georges Clémenceau, the renowned French statesman and former Prime Minister, is estimated to have a net worth of $1.6 million in 2025. Throughout his political career, Clémenceau earned a reputation for his strong leadership and uncompromising stance, particularly during World War I. As one of the main architects of the Treaty of Versailles, he played a significant role in shaping the post-war landscape. Aside from his political achievements, Clémenceau was also an accomplished journalist and writer. His contributions to French society and his notable net worth are testaments to his enduring legacy as a key figure in French history.

The treaty, with all its complex clauses, will only be worth what you are worth; it will be what you make it...What you are going to vote to-day is not even a beginning, it is a beginning of a beginning. The ideas it contains will grow and bear fruit. You have won the power to impose them on a defeated Germany. We are told that she will revive. All the more reason not to show her that we fear her...M. Marin went to the heart of the question, when he turned to us and said in despairing tones, ‘You have reduced us to a policy of vigilance.’ Yes, M. Marin, do you think that one could make a treaty which would do away with the need for vigilance among the nations of Europe who only yesterday were pouring out their blood in battle? Life is a perpetual struggle in war, as in peace...That struggle cannot be avoided. Yes, we must have vigilance, we must have a great deal of vigilance. I cannot say for how many years, perhaps I should say for how many centuries, the crisis which has begun will continue. Yes, this treaty will bring us burdens, troubles, miseries, difficulties, and that will continue for long years.

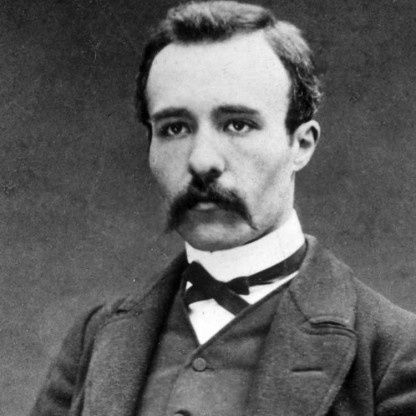

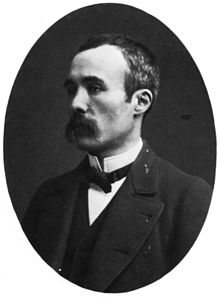

Clemenceau was a native of the Vendée, born at Mouilleron-en-Pareds. During the period of the French Revolution, the Vendée had been a hotbed of monarchist sympathies, but by the time of his birth, its people were fiercely republican. The region was remote from Paris, rural and poor. His mother, Sophie Eucharie Gautreau (1817–1903), was of Huguenot descent. His father, Benjamin Clemenceau (1810–1897), came from a long line of Physicians, but he lived off his lands and Investments and did not practice Medicine. Benjamin was a political activist; he was arrested and briefly held in 1851 and again in 1858. He instilled in his son a love of learning, devotion to radical politics, and a hatred of Catholicism. The Lawyer Albert Clemenceau (1861–1955) was his brother. His mother was devoutly Protestant; his father was an atheist, and insisted that his children should have no religious education. Georges was interested in religious issues. He was a lifelong atheist with a sound knowledge of the Bible. He became a leader of anti-clerical or "Radical" forces that battled against the Catholic Church in France and the Catholics in politics. He stopped short of the more extreme attacks. His position was that if church and state were kept rigidly separated, he would not support oppressive measures designed to further weaken the Church.

In Paris, the young Clemenceau became a political Activist and Writer. In December 1861, he co-founded a weekly newsletter, Le Travail, along with some friends. On 23 February 1862, he was arrested by the police for having placed posters summoning a demonstration. He spent 77 days in the Mazas Prison.

Clemenceau worked in New York City in the years 1865-69, following the American Civil War. He maintained a medical practice, but spent much of his time on political journalism for a Parisian newspaper. He taught French at the home of Calvin Rood in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, and also taught and rode horseback at a private girls' school in Stamford, Connecticut.

On 23 June 1869, he married one of his students, Mary Eliza Plummer (1848-1922), in New York City. She was the daughter of william Kelly Plummer and wife Harriet A. Taylor. The Clemenceaus had three children together before the marriage ended in a contentious divorce.

Clemenceau returned to Paris after the French defeat at the Battle of Sedan in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War and the fall of the Second French Empire. After returning to medical practice as a physician in Vendée, he was appointed mayor of the 18th arrondissement of Paris, including Montmartre, and was also elected to the National Assembly for the 18th arrondissement. When the Paris Commune seized power in March 1871, he tried unsuccessfully to find a compromise between the more radical Leaders of the commune and the more conservative French government. The Commune declared that he had no legal authority to be mayor and seized the city hall of the 18th arrondissement. He ran for election to the Paris Commune council, but received less than eight hundred votes and took no part in its governance. He was in Bordeaux when the Commune was suppressed by the French Army in May 1871.

After the fall of the Commune, he was elected to the Paris municipal council on 23 July 1871 for the Clignancourt quarter, and retained his seat till 1876. He first held the offices of secretary and vice-president, then became President in 1875.

In 1876, Clemenceau stood for the Chamber of Deputies (which replaced the National Assembly in 1875) and was elected for the 18th arrondissement. He joined the far left, and his Energy and mordant eloquence speedily made him the leader of the radical section. In 1877, after the Crisis of 16 May 1877, he was one of the republican majority who denounced the ministry of the Duc de Broglie. He led resistance to the anti-republican policy of which the incident of 16 May was a manifestation. In 1879 his demand for the indictment of the Broglie ministry brought him prominence.

In 1880, Clemenceau started his newspaper La Justice, which became the principal organ of Parisian Radicalism. From this time, throughout the presidency of Jules Grévy (1879-1887), he became widely known as a political critic and destroyer of ministries (le Tombeur de ministères) who avoided taking office himself. Leading the far left in the Chamber of Deputies, he was an active opponent of the colonial policy of Prime Minister Jules Ferry, which he opposed on moral grounds and also as a form of diversion from the more important goal of “Revenge against Germany” for the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine after the Franco-Prussian War. In 1885, his criticism of the conduct of the Sino-French War contributed strongly to the fall of the Ferry cabinet that year.

During the French legislative elections of 1885, he advocated a strong radical programme and was returned both for his old seat in Paris and for the Var, district of Draguignan. He chose to represent the latter in the Chamber of Deputies. Refusing to form a ministry to replace the one he had overthrown, he supported the right in keeping Prime Minister Charles de Freycinet in power in 1886 and was responsible for the inclusion of Georges Ernest Boulanger in the Freycinet cabinet as War Minister. When General Boulanger revealed himself as an ambitious pretender, Clemenceau withdrew his support and became a vigorous opponent of the heterogeneous Boulangist movement, though the radical press continued to patronize the general.

By his exposure of the Wilson scandal, and by his personal plain speaking, Clemenceau contributed largely to Jules Grévy's resignation of the presidency of France in 1887. He had declined Grévy's request to form a cabinet upon the downfall of the cabinet of Maurice Rouvier by advising his followers to vote for neither Charles Floquet, Jules Ferry, nor Charles de Freycinet, he was primarily responsible for the election of an "outsider," Marie François Sadi Carnot, as President.

The split in the Radical Party over Boulangism weakened his hand, and its collapse meant that moderate republicans did not need his help. A further misfortune occurred in the Panama affair, as Clemenceau's relations with the businessman and Politician Cornelius Herz led to his being included in the general suspicion. In response to accusations of corruption leveled by the nationalist Politician Paul Déroulède, Clemenceau fought a duel with him on 23 December 1892. Six shots were discharged, but neither participant was injured.

After his 1893 defeat, Clemenceau confined his political activities to journalism for nearly a decade. His career was further clouded by the long-drawn-out Dreyfus case, in which he took an active part as a supporter of Émile Zola and an opponent of the anti-Semitic and nationalist campaigns. In all, Clemenceau published 665 articles defending Dreyfus during the affair.

On 13 January 1898, Clemenceau published Émile Zola's "J'accuse" on the front page of the Paris daily newspaper L'Aurore, of which he was owner and Editor. He decided to run the controversial article, which would become a famous part of the Dreyfus Affair, in the form of an open letter to Félix Faure, the President of France.

In 1900, he withdrew from La Justice to found a weekly review, Le Bloc, to which he was practically the sole contributor. The publication of Le Bloc lasted until 15 March 1902. On 6 April 1902, he was elected senator for the Var district of Draguignan, although he had previously called for the suppression of the French Senate, as he considered it a strong-house of conservatism. He served as the senator for Draguignan until 1920.

Clemenceau sat with the Radical-Socialist Party in the Senate and moderated his positions, although he still vigorously supported the ministry of Prime Minister Émile Combes, who spearheaded the anti-clericalist republican struggle. In June 1903, he undertook the direction of the journal L'Aurore, which he had founded. In it, he led the campaign to revisit the Dreyfus affair, and to create a separation of Church and State in France. The latter was implemented by the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State.

The miners' strike in the Pas de Calais after the Courrières mine disaster, which resulted in the death of more than one thousand persons, threatened widespread disorder on 1 May 1906. Clemenceau ordered the military against the strikers and repressed the wine-growers' strike in the Languedoc-Roussillon. His actions alienated the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) socialist party, from which he definitively broke in his notable reply in the Chamber of Deputies to Jean Jaurès, leader of the SFIO, in June 1906. Clemenceau's speech positioned him as the strong man of the day in French politics; when the Sarrien ministry resigned in October, Clemenceau became premier.

After a proposal by the deputy Paul Dussaussoy for limited women's suffrage in local elections, Clemenceau published a pamphlet in 1907 in which he declared that if women were given the vote France would return to the Middle Ages. As the revolt of the Languedoc winegrowers developed Clemenceau at first dismissed the complaints, then sent in troops to keep the peace in June 1907. During 1907 and 1908, he led the development of a new Entente cordiale with Britain, which gave France a successful role in European politics. Difficulties with Germany and criticism by the Socialist party in connection with the handling of the First Moroccan Crisis in 1905–06 were settled at the Algeciras Conference.

Between 1909 and 1912, Clemenceau dedicated his time to travel, conferences and the treatment of his illness. He went to South America in 1910, traveling to Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina (where he went as far as Santa Ana de Tucuman in North West Argentina). There, he was amazed by the influence of French culture and of the French Revolution on local elites.

He published the first issue of the Journal du Var on 10 April 1910. Three years later, on 6 May 1913, he founded L'Homme libre ("The Free Man") newspaper in Paris, for which he wrote a daily editorial. In these media, Clemenceau focused increasingly on foreign policy and condemned the Socialists' anti-militarism.

In spite of the censorship imposed by the French government on Clemenceau's journalism at the beginning of World War I, he still wielded considerable political influence. As soon as the war started, Clemenceau advised Interior Minister Malvy to invoke Carnet B, a list of known and suspected subversives who were supposed to be arrested on mobilisation. The Prefect of Police gave the same advice, but the government did not follow it, with the result that 80% of the 2,501 people listed on Carnet B volunteered for Service. Clemenceau declined to join the government of national unity as Justice Minister in autumn 1914.

When Clemenceau became prime minister in 1917 victory seemed to be elusive. There was little activity on the Western Front because it was believed that there should be limited attacks until the American support arrived. At this time, Italy was on the defensive, Russia had virtually stopped fighting – and it was believed (correctly - see the Treaty of Brest Litovsk) that they would be making a separate peace with Germany. At home, the government had to deal with increasing demonstrations against the war, a scarcity of resources and air raids that were causing huge physical damage to Paris as well as undermining the morale of its citizens. It was also believed that many politicians secretly wanted peace. It was a challenging situation for Clemenceau; after years of criticizing other men during the war, he suddenly found himself in a position of supreme power. He was also isolated politically. He did not have close links with any parliamentary Leaders (especially after he had antagonized them so relentlessly during the course of the war) and so had to rely on himself and his own circle of friends.

When Clemenceau returned to the Council of Ten on 1 March he found that little had changed. One issue that had not changed at all was a dispute over France's long-running eastern frontier and control of the German Rhineland. Clemenceau believed that Germany's possession of this territory left France without a natural frontier in the East and thus simplified invasion into France for an attacking army. The British ambassador reported in December 1918 on Clemenceau's views on the Future of the Rhineland: "He said that the Rhine was a natural boundary of Gaul and Germany and that it ought to be made the German boundary now, the territory between the Rhine and the French frontier being made into an Independent State whose neutrality should be guaranteed by the great powers".

In 1919 France adopted a new electoral system and the legislative election gave the National Bloc (a coalition of right-wing parties) a majority. Clemenceau only intervened once in the election campaign, delivering a speech on 4 November at Strasbourg, praising the manifesto and men of the National Bloc and urging that the victory in the war needed to be safeguarded by vigilance. In private he was concerned at this huge swing to the right.

He took a holiday in Egypt and the Sudan from February to April 1920, then embarked for the Far East in September, returning to France in March 1921. In June, he visited England and received an honorary degree from the University of Oxford. He met Lloyd George and said to him that after the Armistice he had become the enemy of France. Lloyd George replied, “Well, was not that always our traditional policy?” He was joking, but after reflection, Clemenceau took it seriously. After Lloyd George's fall from power in 1922 Clemenceau remarked, “As for France, it is a real enemy who disappears. Lloyd George did not hide it: at my last visit to London he cynically admitted it”.

Clemenceau was a long-time friend and supporter of the impressionist Painter Claude Monet. He was instrumental in persuading Monet to have a cataract operation in 1923, and for over a decade encouraged Monet to complete his donation to the French state of Les Nymphéas (Water Lilies) paintings that are now on display in Paris' Musée de l'Orangerie in specially constructed oval galleries (which opened to the public in 1927).

In late 1922, Clemenceau gave a lecture tour in the major cities of the American northeast. He defended the policy of France, including war debts and reparations, and condemned American isolationism. He was well received and attracted large audiences, but America's policy remained unchanged. On 9 August 1926, he wrote an open letter to the American President Calvin Coolidge that argued against France paying all its war debts: "France is not for sale, even to her friends". This appeal went unheard.

Clemenceau died on 24 November 1929 and was buried at Mouchamps.

Clemenceau often joked about the "assassin's" bad marksmanship – “We have just won the most terrible war in history, yet here is a Frenchman who misses his target 6 out of 7 times at point-blank range. Of course this fellow must be punished for the careless use of a dangerous weapon and for poor marksmanship. I suggest that he be locked up for eight years, with intensive training in a shooting gallery."

Clemenceau was not experienced in the fields of economics or Finance, and as John Maynard Keynes pointed out "he did not trouble his head to understand either the Indemnity or [France’s] overwhelming financial difficulties", but he was under strong public and parliamentary pressure to make Germany's reparations bill as large as possible. It was generally agreed that Germany should not pay more than it could afford, but the estimates of what it could afford varied greatly. Figures ranged between £2,000 million and £20,000 million. Clemenceau realised that any compromise would anger both the French and British citizens and that the only option was to establish a reparations commission which would examine Germany's capacity for reparations. This meant that the French government was not directly involved in the issue of reparations.