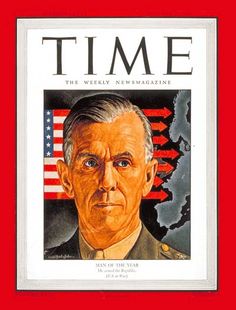

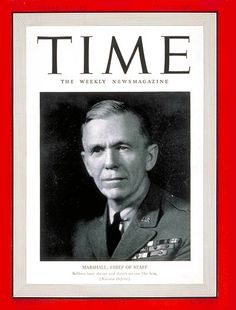

After the war, Marshall was assigned as an aide-de-camp to John J. Pershing, who was then serving as the Army's Chief of Staff. He later served on the Army staff, commanded the 15th Infantry Regiment in China, and was an instructor at the Army War College. In 1927, he became assistant commandant of the Army's Infantry School, where he modernized command and staff processes, which proved to be of major benefit during World War II. In 1932 and 1933 he commanded the 8th Infantry Regiment and Fort Screven, Georgia. Marshall commanded 5th Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division and Vancouver Barracks from 1936 to 1938, and received promotion to brigadier general. During this command, Marshall was also responsible for 35 Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in Oregon and southern Washington. In July 1938, Marshall was assigned to the War Plans Division on the War Department staff, and he was subsequently appointed as the Army's Deputy Chief of Staff. When Chief of Staff Malin Craig retired in 1939, Marshall became acting Chief of Staff, and then Chief of Staff. He served as Chief of Staff until the end of the war in 1945.