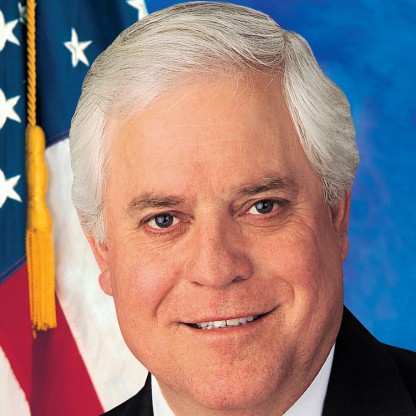

Bruce Fairchild Barton, an esteemed American author, is anticipated to possess a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in the year 2025. Barton, renowned for his literary contributions, has made a significant impact on the literary landscape of the United States. Through his captivating works, he has captured the imagination of readers, culminating in both critical acclaim and commercial success. With his exemplary talent for storytelling, Barton has amassed substantial wealth, reflecting his immense influence and popularity within the American literary community.

Dear Mr. Blank,

For the past three or four years things have been going pretty well at our house. We pay our bills, afford such luxuries as having the children's tonsils out, and still have something in the bank at the end of the year. So far as business is concerned, therefore, I have felt fairly well content.

But there is another side to a man, which every now and then gets restless. It says: "What good are you anyway? What influences have you set up, aside from your business, that would go on working if you were to shuffle off tomorrow?"

Of course, we chip in to the Church and the Salvation Army, and dribble out a little money right along in response to all sorts of appeals. But there isn't much satisfaction in it. For one thing, it's too diffused and, for another, I'm never very sure in my own mind that the thing I'm giving to is worth a hurrah and I don't have time to find out.

A couple of years ago I said: "I'd like to discover the one place in the United States where a dollar does more net good than anywhere else." It was a rather thrilling idea, and I went at it in the same spirit in which our advertising agency conducts a market investigation for a manufacturer. Without bothering you with a long story, I believe I have found the place.

This letter is being mailed to 23 men besides yourself, twenty-five of us altogether. I honestly believe that it offers an opportunity to get a maximum amount of satisfaction for a minimum sum.

Let me give you the background.

Among the first comers to this country were some pure blooded English folks who settled in Virginia but, being more hardy and venturesome than the average, pushed on west and settled in the mountains of Kentucky, Tennessee, North and South Carolina. They were stalwart lads and lassies. They fought the first battle against the British and shed the first blood. In the Revolution they won the battle of King's Mountain. Later, under Andy Jackson, they fought and won the only land victory that we managed to pull off in the War of 1812. Although they lived in southern states they refused to secede in 1860. They broke off from Virginia and formed the state of West Virginia; they kept Kentucky in the Union; and they sent a million men into the northern armies. It is not too much to say that they were the deciding factor in winning the struggle to keep these United States united.

They have had a rotten deal from Fate. There are no roads into the mountains, no trains, no ways of making money. So our prosperity has circled all around them and left them pretty much untouched. They are great folks. The girls are as good looking as any in the world. Take one of them out of her two-roomed log cabin home, give her a stylish dress and a permanent wave, and she'd be a hit on Fifth Avenue. Take one of the boys, who maybe never saw a railroad train until he was 21: give him a few years of education and he goes back into the mountains as a teacher or doctor or lawyer or carpenter, and changes the life of a town or county.

This gives you an idea of the raw material. Clean, sound timber – no knots, no wormholes; a great contrast to the imported stuff with which our social settlements have to work in New York and other cities.

Now, away back in the Civil War days, a little college was started in the Kentucky mountains. It started with faith, hope, and sacrifice, and those three virtues are the only endowment it has ever had. Yet today it has accumulated, by little gifts picked up by passing the hat, a plant that takes care of 3000 students a year. It's the most wonderful manufacturing proposition you ever heard of. They raise their own food, can it in their own cannery; milk their own cows; make brooms and weave rugs that are sold all over the country; do their own carpentry, painting, printing, horseshoeing, and everything, teaching every boy and girl a trade while he and she is studying. And so efficiently is the job done that –

- a room rents for 60 cents a week (including heat and light)

- meals are 11 cents apiece (yet all the students gain weight on the faire; every student gets a quart of milk a day)

- the whole cost to a boy or girl for a year's study – room, board, books, etc., – is $146. More than half of this the student earns by work; many students earn all.

One boy walked in a hundred miles, leading a cow. He stabled the cow in the village, milked her night and morning, peddled the milk, and put himself through college. He is now a major in the United States Army. His brother, who owned half of the cow, is a missionary in Africa. Seventy-five percent of the graduates go back to the mountains, and their touch is on the mountain counties of five states; better homes, better food, better child health, better churches, better schools; no more feuds; lower death rates.

Now we come to the hook. It costs this college, which is named Berea, $100 a year per student to carry on. She could, of course, turn away 1500 students each year and break even on the other 1500. Or she could charge $100 tuition. But then she would be just one more college for the well-to-do. Either plan would be a moral crime. The boys and girls in those one-room and two-room cabins deserve a chance. They are of the same stuff as Lincoln and Daniel Boone and Henry Clay; they are the very best raw material that can be found in the United States.

I have agreed to take ten boys and pay the deficit on their education each year, $1,000. I have agreed to do this if I can get twenty-four other men who will each take ten. The president, Dr. William J. Hutchins (Yale 1892), who ought to be giving every minute of his time to running the college, is out passing the hat and riding the rails from town to town. He can manage to get $50,000 or $70,000 a year. I want to lift part of his load by turning in $25,000.

This is my proposition to you. Let me pick out ten boys, who are as sure blooded Americans as your own sons, and just as deserving of a chance. Let me send you their names and tell you in confidence, for we don't want to hurt their pride, where they come from and what they hope to do with their lives. Let me report to you on their progress three times a year. You write me, using the enclosed envelope, that, if and when I get my other twenty-three men, you will send President Hutchins your check for $1,000. If you will do this I'll promise you the best time you have ever bought for a thousand dollars.

Most of the activities to which we give in our lives stop when we stop. But our families go on; and young life goes on and matures and gives birth to other lives. For a thousand dollars a year you can put ten boys or girls back into the mountains who will be a leavening influence in ten towns or counties, and their children will bear the imprint of your influence. Honestly, can you think of any other investment that would keep your life working in the world so long a time after you are gone?

This is a long letter, and I could be writing a piece for the magazines and collecting for it in the time it has taken me to turn it out. So, remember that this is different from any other appeal that ever came to you. Most appeals are made by people who profit from a favorable response, but this appeal is hurting me a lot more than it can possibly hurt you. What will you have, ten boys or ten girls?

Cordially yours,

Bruce Barton 1