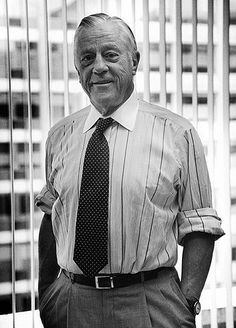

| Who is it? | Newspaper Editor & Journalist |

| Birth Day | August 26, 1921 |

| Birth Place | Boston, United States |

| Age | 99 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | October 21, 2014(2014-10-21) (aged 93)\nWashington, D.C. |

| Birth Sign | Virgo |

| Resting place | Oak Hill Cemetery, Washington, D.C. |

| Residence | Laird-Dunlop House, Washington, D.C. |

| Education | Dexter School, St. Marks School |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Occupation | Newspaper editor |

| Employer | The Washington Post |

| Known for | Role in exposing the Pentagon Papers and the Watergate scandal |

| Spouse(s) | Jean Saltonstall (m. 1942; divorced) Antoinette Pinchot (m. 1957; divorced) Sally Quinn (m. 1978–2014; his death) |

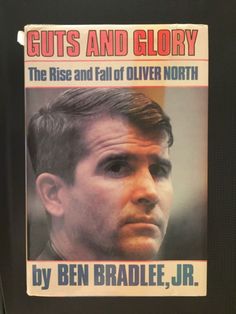

| Children | Ben Jr., Dominic (Dino), Marina, Quinn |

| Relatives | Choate family Crowninshield family Sargent family Putnam family |

| Awards | Knight of the National Order of the Legion of Honor Presidential Medal of Freedom |

Ben Bradlee, a renowned newspaper editor and journalist in the United States, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in the year 2025. Bradlee gained prominence for his influential work as the executive editor of The Washington Post, particularly during the Watergate scandal, which ultimately led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon. As an influential figure in the field of journalism, Bradlee has undoubtedly made significant contributions to the industry throughout his career, thereby accumulating a noteworthy net worth.

You had a lot of Cuban or Spanish-speaking guys in masks and rubber gloves, with walkie-talkies, arrested in the Democratic National Committee Headquarters at 2 in the morning. What the hell were they in there for? What were they doing? The follow-up story was based primarily on their arraignment in court, and it was based on information given our police reporter, Al Lewis, by the cops, showing them an address book that one of the burglars had in his pocket, and in the address book was the name 'Hunt,' H-u-n-t, and the phone number was the White House phone number, which Al Lewis and every reporter worth his salt knew. And when, the next day, Woodward—this is probably Sunday or maybe Monday, because the burglary was Saturday morning early—called the number and asked to speak to Mr. Hunt, and the operator said, 'Well, he's not here now; he's over at' such-and-such a place, gave him another number, and Woodward called him up, and Hunt answered the phone, and Woodward said, 'We want to know why your name was in the address book of the Watergate burglars.' And there is this long, deathly hush, and Hunt said, 'Oh my God!' and hung up. So you had the White House. You have Hunt saying 'Oh my God!' At a later arraignment, one of the guys whispered to a judge. The judge said, 'What do you do?' and Woodward overheard the words 'CIA.' So if your interest isn't whetted by this time, you're not a journalist.

At The Washington Post, Bradlee carried the title vice President at large. He and Quinn lived at the Todd Lincoln House in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. The middle part of the house was built in 1792. They also restored Porto Bello, their home in Drayden, Maryland.

A member of the Boston Brahmin Crowninshield family, Bradlee was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on August 26, 1921. His father was Frederick Josiah Bradlee, Jr. (1892–1970), a direct descendant of Nathan Bradley—the first American Bradley, born in the colony of Massachusetts in 1631. His mother, Josephine de Gersdorff (1896–1975), was awarded the French Legion of Honour for starting an orphanage that sheltered children from Nazi Germany during World War II. Bradlee's maternal grandfather, Carl August de Gersdorff (1865–1944), the son of a German immigrant, was a wealthy New York Lawyer. Bradlee's maternal grandmother was Helen Suzette Crowninshield (1868–1941), daughter of Artist Frederic Crowninshield (1845–1918), another member of the Crowninshield family. His great-great-uncle was U.S. Lawyer Joseph Hodges Choate, 34th U.S. ambassador to Britain, and his great uncle was Francis Welch "Frank" Crowninshield, the creator and Editor of Vanity Fair, and a roommate of Condé Nast. He had a brother named Frederick Bradlee (1919–2003), a Writer and Broadway stage actor.

Bradlee, the second of three children, grew up in a wealthy family with domestic staff. With his brother, Freddy, and sister, Constance, he learned French, took piano lessons, and went to the symphony and the opera. The stock market crash of 1929 decimated the family's wealth however. During the Great Depression, Bradlee's father worked odd jobs to support his family, including keeping the books for various clubs and institutions and supervising the janitors at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Bradlee's first marriage was to Jean Saltonstall, who also came from a wealthy and prominent Boston Brahmin family. They married on August 8, 1942, and had one son, Ben Bradlee Jr., who became a deputy managing Editor of The Boston Globe.

After the war, in 1946, Bradlee became a reporter at the New Hampshire Sunday News, a venture he helped launch. After he sold the paper, in 1948 he started working for The Washington Post as a reporter. He got to know associate publisher Philip Graham, who was the son-in-law of the publisher, Eugene Meyer. On November 1, 1950, Bradlee was alighting from a streetcar in front of the White House just as two Puerto Rican nationalists attempted to shoot their way into Blair House in an attempt to kill President Harry S. Truman. In 1951 Graham helped Bradlee become assistant press attaché in the American embassy in Paris

As a reporter in the 1950s, Bradlee became close friends with then-senator John F. Kennedy, who had graduated from Harvard two years before Bradlee, and lived nearby. In 1960 Bradlee toured with both Kennedy and Richard Nixon in their presidential campaigns. He later wrote a book, Conversations With Kennedy (W.W. Norton, 1975), recounting their relationship during those years. Bradlee was, at this point, Washington Bureau chief for Newsweek, a position from which he helped negotiate the sale of the magazine to The Washington Post holding company. Bradlee maintained that position until being promoted to managing Editor at the Post in 1965. He became executive Editor in 1968.

In 1952, Bradlee joined the staff of the Office of U.S. Information and Educational Exchange (USIE), the embassy's propaganda unit. USIE produced films, magazines, research, speeches, and news items for use by the CIA throughout Europe. USIE (later known as USIA) also controlled the Voice of America, a means of disseminating pro-American "cultural information" worldwide. While at the USIE, according to a Justice Department memo from an assistant U.S. attorney in the Rosenberg Trial, Bradlee was helping the CIA manage European propaganda regarding the spying conviction and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on June 19, 1953. The memo, addressed to U.S. Attorney Myles Lane and dated December 13, 1952, states that "[Mr. Bradlee] further advised that he was sent here by Robert Thayer, who is the head of the CIA in Paris...he stated that he was supposed to have been met by a representative of the CIA at the airport but missed connections" and that "he has been trying to get in touch with [CIA Director] Allen Dulles."

In 1957, while working as a reporter for Newsweek, Bradlee created controversy when he interviewed members of the FLN. They were Algerian guerrillas who were in rebellion against the French government at the time. According to Deborah Davis, author of the Katharine Graham biography Katharine the Great, this had all the "earmarks of an intelligence operation". As a result of these interviews, Bradlee was forced to leave France.

Bradlee has drawn criticism from several quarters for his perjury at the 1965 trial of the man accused of murdering Bradlee's sister-in-law Mary Pinchot Meyer, who was shot to death on October 12, 1964 while walking on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal towpath in Georgetown. Attorneys for both the prosecution and the defense (Alfred Hantman and Dovey J. Roundtree), in addition to D.C. Police Detective Bernie Crooke, along with authors Peter Janney and Nina Burleigh, have all noted the significant difference between the limited information Bradlee divulged under oath at the 1965 trial, and what he revealed 30 years later in his 1995 memoir A Good Life.

Under Bradlee's leadership, The Washington Post took on major challenges during the Nixon administration. In 1971 The New York Times and the Post successfully challenged the government over the right to publish the Pentagon Papers. One year later, Bradlee backed reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein as they probed the break-in at the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate Hotel. According to Bradlee:

Ensuing investigations of suspected cover-ups led inexorably to congressional committees, conflicting testimonies, and ultimately to the resignation of Richard Nixon in 1974. For decades, Bradlee was one of only four publicly known people who knew the true identity of press informant Deep Throat, the other three being Woodward, Bernstein, and Deep Throat himself, who later revealed himself to be Nixon's FBI associate Director Mark Felt.

After Bradlee and Pinchot divorced, Bradlee married fellow Journalist Sally Quinn on October 20, 1978. Quinn and Bradlee had one child, Quinn Bradlee, who was born in 1982 when Quinn was 41 and Bradlee was 61. In 2009 they appeared with Quinn Bradlee on the Charlie Rose Show on PBS and spoke of their son's having been born with Velo-cardio-facial syndrome, also known as DiGeorge syndrome.

In 1981 Post reporter Janet Cooke won a Pulitzer Prize for "Jimmy's World", a profile of an 8-year-old heroin addict. Cooke's article turned out to be fiction: there was no such addict. As executive Editor, Bradlee was roundly criticized in many circles for failing to ensure the article's accuracy. After questions about the story's veracity arose, Bradlee (along with publisher Donald Graham) ordered a "full disclosure" investigation to ascertain the truth. Bradlee personally apologized to Mayor Marion Barry and the chief of police of Washington, D.C., for the Post's fictitious article. Cooke, meanwhile, was forced to resign and relinquish the Pulitzer.

In a 1991 interview with the late author Leo Damore, prosecuting attorney Hantman said that having knowledge of the diary at the trial “could have changed everything.” In her 2009 autobiography, Justice Older than the Law, defense counsel Dovey Johnson Roundtree expresses shock at learning of the diary’s significance from Bradlee’s book, and states, “James Angleton’s awareness of the diary’s existence and his interest in finding it, reading it, and destroying it – all of that unsettled me deeply when I read Mr. Bradlee’s 1995 account, as did his insistence that the diary was a private document…Had I been aware of it, I would have felt compelled to pursue it.”

In his 1995 memoir A Good Life, Bradlee revealed that his sister-in-law’s diary contained information about her affair with the late President Kennedy and the fact that Bradlee had conspired with CIA counterintelligence chief James Angleton and others to destroy it. At the 1965 trial, however, he failed to mention the diary when asked under oath what he had found when searching her studio on the night of the murder.

In recognition of his work as Editor of The Washington Post, Bradlee won the Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism in 1998.

In the fall of 2005, Jim Lehrer conducted six hours of interviews with Bradlee on a variety of topics, from the responsibilities of the press to Watergate to the Valerie Plame affair. The interviews were edited for an hour-long documentary, Free Speech: Jim Lehrer and Ben Bradlee, which premiered on PBS on June 19, 2006.

Bradlee was named as a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama on August 8, 2013, and was presented the medal at a White House ceremony on November 20, 2013.

Bradlee spent his final years suffering with dementia. In late September 2014, he entered hospice care due to declining health as a result of Alzheimer's disease. He died of natural causes on October 21, 2014, at his home in Washington, D.C., at the age of 93. His funeral was held at the Washington National Cathedral on October 29. He was buried at the Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C. The Daily Beast paid tribute to Bradlee by posting his quote, "Today Our Best, Tomorrow Better" on the wall of their office.

Pinchot Meyer biographers Janney and Burleigh have both criticized Bradlee's omission of substantial information under oath. "Bradlee had excoriated Cord Meyer [Pinchot Meyer’s ex-husband] for his 'derisive scorn' for the people's right to know in the 1960s, but the rules changed when the subject of a story was his sister-in-law," author Burleigh wrote. "The First Amendment champion of the Watergate investigation admitted in his memoir that he gave Mary Meyer's diary to the CIA because it was 'a family document.'"