| Who is it? | Economist and Philosopher |

| Birth Day | June 16, 1723 |

| Birth Place | Kirkcaldy, Scotland, Welsh |

| Age | 296 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 17 July 1790(1790-07-17) (aged 67)\nEdinburgh, Scotland |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Alma mater | University of Glasgow Balliol College, Oxford |

| Notable work | The Wealth of Nations The Theory of Moral Sentiments |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Classical economics, classical liberalism |

| Main interests | Political philosophy, ethics, economics |

| Notable ideas | Classical economics, modern free market, division of labour, the "invisible hand" |

Adam Smith, the renowned economist and philosopher from Wales, is projected to have a net worth of approximately $800,000 in 2025. Smith's contributions to the field of economics, particularly his work in theories of free markets and capitalism, have earned him widespread recognition and influence. Known for his influential book, "The Wealth of Nations," Smith's ideas have shaped economic policies and thinking across the globe. Despite his significant intellectual legacy, it is noteworthy that Smith's estimated net worth remains comparatively modest, highlighting his dedication to the pursuit of knowledge over personal wealth.

As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it.

Smith was born in Kirkcaldy, in the County of Fife, Scotland. His father, also Adam Smith, was a Scottish Writer to the Signet (senior solicitor), advocate and prosecutor (Judge Advocate) and also served as comptroller of the Customs in Kirkcaldy. In 1720, he married Margaret Douglas, daughter of the landed Robert Douglas of Strathendry, also in Fife. His father died two months after he was born, leaving his mother a widow. The date of Smith's baptism into the Church of Scotland at Kirkcaldy was 5 June 1723 and this has often been treated as if it were also his date of birth, which is unknown. Although few events in Smith's early childhood are known, the Scottish Journalist John Rae, Smith's biographer, recorded that Smith was abducted by gypsies at the age of three and released when others went to rescue him. Smith was close to his mother, who probably encouraged him to pursue his scholarly ambitions. He attended the Burgh School of Kirkcaldy—characterised by Rae as "one of the best secondary schools of Scotland at that period"—from 1729 to 1737, he learned Latin, mathematics, history, and writing.

Smith entered the University of Glasgow when he was fourteen and studied moral philosophy under Francis Hutcheson. Here, Smith developed his passion for liberty, reason and free speech. In 1740, Smith was the graduate scholar presented to undertake postgraduate studies at Balliol College, Oxford, under the Snell Exhibition.

Smith considered the teaching at Glasgow to be far superior to that at Oxford, which he found intellectually stifling. In Book V, Chapter II of The Wealth of Nations, Smith wrote: "In the University of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching." Smith is also reported to have complained to friends that Oxford officials once discovered him reading a copy of David Hume's Treatise on Human Nature, and they subsequently confiscated his book and punished him severely for reading it. According to william Robert Scott, "The Oxford of [Smith's] time gave little if any help towards what was to be his lifework." Nevertheless, Smith took the opportunity while at Oxford to teach himself several subjects by reading many books from the shelves of the large Bodleian Library. When Smith was not studying on his own, his time at Oxford was not a happy one, according to his letters. Near the end of his time there, Smith began suffering from shaking fits, probably the symptoms of a nervous breakdown. He left Oxford University in 1746, before his scholarship ended.

Smith began delivering public lectures in 1748 in Edinburgh, sponsored by the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh under the patronage of Lord Kames. His lecture topics included rhetoric and belles-lettres, and later the subject of "the progress of opulence". On this latter topic he first expounded his economic philosophy of "the obvious and simple system of natural liberty". While Smith was not adept at public speaking, his lectures met with success.

In 1750, Smith met the Philosopher David Hume, who was his senior by more than a decade. In their writings covering history, politics, philosophy, economics and religion, Smith and Hume shared closer intellectual and personal bonds than with other important figures of the Scottish Enlightenment.

In 1751, Smith earned a professorship at Glasgow University teaching logic courses, and in 1752 he was elected a member of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh, having been introduced to the society by Lord Kames. When the head of Moral Philosophy in Glasgow died the next year, Smith took over the position. He worked as an academic for the next thirteen years, which he characterised as "by far the most useful and therefore by far the happiest and most honorable period [of his life]".

Smith used the term "the invisible hand" in "History of Astronomy" referring to "the invisible hand of Jupiter," and once in each of his The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and The Wealth of Nations (1776). This last statement about "an invisible hand" has been interpreted in numerous ways.

In 1762, the University of Glasgow conferred on Smith the title of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.). At the end of 1763, he obtained an offer from Charles Townshend—who had been introduced to Smith by David Hume—to tutor his stepson, Henry Scott, the young Duke of Buccleuch. Smith then resigned from his professorship to take the tutoring position. He subsequently attempted to return the fees he had collected from his students because he resigned in the middle of the term, but his students refused.

In 1766, Henry Scott's younger brother died in Paris, and Smith's tour as a tutor ended shortly thereafter. Smith returned home that year to Kirkcaldy, and he devoted much of the next ten years to his magnum opus. There he befriended Henry Moyes, a young blind man who showed precocious aptitude. As well as teaching Moyes, Smith secured the patronage of David Hume and Thomas Reid in the young man's education. In May 1773, Smith was elected fellow of the Royal Society of London, and was elected a member of the Literary Club in 1775. The Wealth of Nations was published in 1776 and was an instant success, selling out its first edition in only six months.

There is disagreement between classical and neoclassical economists about the central message of Smith's most influential work: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). Neoclassical economists emphasise Smith's invisible hand, a concept mentioned in the middle of his work – Book IV, Chapter II – and classical economists believe that Smith stated his programme for promoting the "wealth of nations" in the first sentences, which attributes the growth of wealth and prosperity to the division of labour.

Smith was also a close friend and later the executor of David Hume, who was commonly characterised in his own time as an atheist. The publication in 1777 of Smith's letter to william Strahan, in which he described Hume's courage in the face of death in spite of his irreligiosity, attracted considerable controversy.

Adam Smith resided at Panmure house from 1778 to 1790. This residence has now been purchased by the Edinburgh Business School at Heriot Watt University and fundraising has begun to restore it. Part of the Northern end of the original building appears to have been demolished in the 19th century to make way for an iron foundry.

Smith died in the northern wing of Panmure House in Edinburgh on 17 July 1790 after a painful illness. His body was buried in the Canongate Kirkyard. On his death bed, Smith expressed disappointment that he had not achieved more.

Smith's literary executors were two friends from the Scottish academic world: the Physicist and Chemist Joseph Black, and the pioneering Geologist James Hutton. Smith left behind many notes and some unpublished material, but gave instructions to destroy anything that was not fit for publication. He mentioned an early unpublished History of Astronomy as probably suitable, and it duly appeared in 1795, along with other material such as Essays on Philosophical Subjects.

Smith's most prominent disciple in nineteenth-century Britain, peace advocate Richard Cobden, preferred the first proposal. Cobden would lead the Anti-Corn Law League in overturning the Corn Laws in 1846, shifting Britain to a policy of free trade and empire "on the cheap" for decades to come. This hands-off approach toward the British Empire would become known as Cobdenism or the Manchester School. By the turn of the century, however, advocates of Smith's second proposal such as Joseph Shield Nicholson would become ever more vocal in opposing Cobdenism, calling instead for imperial federation. As Marc-William Palen notes: "On the one hand, Adam Smith’s late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Cobdenite adherents used his theories to argue for gradual imperial devolution and empire ‘on the cheap’. On the other, various proponents of imperial federation throughout the British World sought to use Smith’s theories to overturn the predominant Cobdenite hands-off imperial approach and instead, with a firm grip, bring the empire closer than ever before." Smith's ideas thus played an important part in subsequent debates over the British Empire.

Classical economists presented competing theories of those of Smith, termed the "labour theory of value". Later Marxian economics descending from classical economics also use Smith's labour theories, in part. The first volume of Karl Marx's major work, Capital, was published in German in 1867. In it, Marx focused on the labour theory of value and what he considered to be the exploitation of labour by capital. The labour theory of value held that the value of a thing was determined by the labour that went into its production. This contrasts with the modern contention of neoclassical economics, that the value of a thing is determined by what one is willing to give up to obtain the thing.

The body of theory later termed "neoclassical economics" or "marginalism" formed from about 1870 to 1910. The term "economics" was popularised by such neoclassical economists as Alfred Marshall as a concise synonym for "economic science" and a substitute for the earlier, broader term "political economy" used by Smith. This corresponded to the influence on the subject of mathematical methods used in the natural sciences. Neoclassical economics systematised supply and demand as joint determinants of price and quantity in market equilibrium, affecting both the allocation of output and the distribution of income. It dispensed with the labour theory of value of which Smith was most famously identified with in classical economics, in favour of a marginal utility theory of value on the demand side and a more general theory of costs on the supply side.

Smith's library went by his will to David Douglas, Lord Reston (son of his cousin Colonel Robert Douglas of Strathendry, Fife), who lived with Smith. It was eventually divided between his two surviving children, Cecilia Margaret (Mrs. Cunningham) and David Anne (Mrs. Bannerman). On the death of her husband, the Reverend W. B. Cunningham of Prestonpans in 1878, Mrs. Cunningham sold some of the books. The remainder passed to her son, Professor Robert Oliver Cunningham of Queen's College, Belfast, who presented a part to the library of Queen's College. After his death the remaining books were sold. On the death of Mrs. Bannerman in 1879, her portion of the library went intact to the New College (of the Free Church) in Edinburgh and the collection was transferred to the University of Edinburgh Main Library in 1972.

The bicentennial anniversary of the publication of The Wealth of Nations was celebrated in 1976, resulting in increased interest for The Theory of Moral Sentiments and his other works throughout academia. After 1976, Smith was more likely to be represented as the author of both The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and thereby as the founder of a moral philosophy and the science of economics. His homo economicus or "economic man" was also more often represented as a moral person. Additionally, economists David Levy and Sandra Peart in "The Secret History of the Dismal Science" point to his opposition to hierarchy and beliefs in inequality, including racial inequality, and provide additional support for those who point to Smith's opposition to slavery, colonialism, and empire. They show the caricatures of Smith drawn by the opponents of views on hierarchy and inequality in this online article. Emphasised also are Smith's statements of the need for high wages for the poor, and the efforts to keep wages low. In The "Vanity of the Philosopher: From Equality to Hierarchy in Postclassical Economics", Peart and Levy also cite Smith's view that a Common street porter was not intellectually inferior to a Philosopher, and point to the need for greater appreciation of the public views in discussions of science and other subjects now considered to be technical. They also cite Smith's opposition to the often expressed view that science is superior to Common sense.

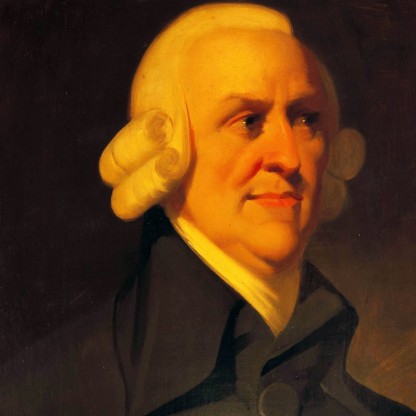

Smith has been commemorated in the UK on banknotes printed by two different banks; his portrait has appeared since 1981 on the £50 notes issued by the Clydesdale Bank in Scotland, and in March 2007 Smith's image also appeared on the new series of £20 notes issued by the Bank of England, making him the first Scotsman to feature on an English banknote.

The Wealth of Nations was a precursor to the modern academic discipline of economics. In this and other works, Smith expounded how rational self-interest and competition can lead to economic prosperity. Smith was controversial in his own day and his general approach and writing style were often satirised by Tory Writers in the moralising tradition of Hogarth and Swift, as a discussion at the University of Winchester suggests. In 2005, The Wealth of Nations was named among the 100 Best Scottish Books of all time. Former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, it is said, used to carry a copy of the book in her handbag.

A large-scale memorial of Smith by Alexander Stoddart was unveiled on 4 July 2008 in Edinburgh. It is a 10 feet (3.0 m)-tall bronze sculpture and it stands above the Royal Mile outside St Giles' Cathedral in Parliament Square, near the Mercat cross. 20th-century Sculptor Jim Sanborn (best known for the Kryptos sculpture at the United States Central Intelligence Agency) has created multiple pieces which feature Smith's work. At Central Connecticut State University is Circulating Capital, a tall cylinder which features an extract from The Wealth of Nations on the lower half, and on the upper half, some of the same text but represented in binary code. At the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, outside the Belk College of Business Administration, is Adam Smith's Spinning Top. Another Smith sculpture is at Cleveland State University. He also appears as the narrator in the 2013 play The Low Road, centred on a proponent on laissez-faire economics in the late eighteenth century but dealing obliquely with the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the recession which followed—in the premiere production, he was portrayed by Bill Paterson.

Paul Samuelson finds in Smith's pluralist use of supply and demand as applied to wages, rents, and profit a valid and valuable anticipation of the general equilibrium modelling of Walras a century later. Smith's allowance for wage increases in the short and intermediate term from capital accumulation and invention contrasted with Malthus, Ricardo, and Karl Marx in their propounding a rigid subsistence–wage theory of labour supply.

Very differently, classical economists see in Smith's first sentences his programme to promote "The Wealth of Nations". Using the physiocratical concept of the economy as a circular process, to secure growth the inputs of Period 2 must exceed the inputs of Period 1. Therefore, those outputs of Period 1 which are not used or usable as inputs of Period 2 are regarded as unproductive labour, as they do not contribute to growth. This is what Smith had heard in France from, among others, Quesnay. To this French insight that unproductive labour should be reduced to use labour more productively, Smith added his own proposal, that productive labour should be made even more productive by deepening the division of labour. Smith argued that deepening the division of labour under competition leads to greater productivity, which leads to lower prices and thus an increasing standard of living—"general plenty" and "universal opulence"—for all. Extended markets and increased production lead to the continuous reorganisation of production and the invention of new ways of producing, which in turn lead to further increased production, lower prices, and improved standards of living. Smith's central message is therefore that under dynamic competition a growth machine secures "The Wealth of Nations". Smith's argument predicted Britain's evolution as the workshop of the world, underselling and outproducing all its competitors. The opening sentences of the "Wealth of Nations" summarise this policy:

In light of the arguments put forward by Smith and other economic theorists in Britain, academic belief in mercantilism began to decline in Britain in the late 18th century. During the Industrial Revolution, Britain embraced free trade and Smith's laissez-faire economics, and via the British Empire, used its power to spread a broadly liberal economic model around the world, characterised by open markets, and relatively barrier free domestic and international trade.

Smith has been alternately described as someone who "had a large nose, bulging eyes, a protruding lower lip, a nervous twitch, and a speech impediment" and one whose "countenance was manly and agreeable." Smith is said to have acknowledged his looks at one point, saying, "I am a beau in nothing but my books." Smith rarely sat for portraits, so almost all depictions of him created during his lifetime were drawn from memory. The best-known portraits of Smith are the profile by James Tassie and two etchings by John Kay. The line engravings produced for the covers of 19th century reprints of The Wealth of Nations were based largely on Tassie's medallion.