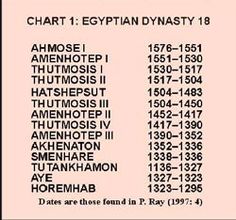

Presuming that it was Thutmose III (rather than his co-regent son), Tyldesley also put forth a hypothesis about Thutmose suggesting that his erasures and defacement of Hatshepsut's monuments could have been a cold, but rational attempt on his part to extinguish the memory of an "unconventional female king whose reign might possibly be interpreted by Future generations as a grave offence against Ma'at, and whose unorthodox coregency" could "cast serious doubt upon the legitimacy of his own right to rule. Hatshepsut's crime need not be anything more than the fact that she was a woman." Tyldesley conjectured that Thutmose III may have considered the possibility that the Example of a successful female king in Egyptian history could demonstrate that a woman was as capable at governing Egypt as a traditional male king, which could persuade "future generations of potentially strong female kings" to not "remain content with their traditional lot as wife, sister and eventual mother of a king" and assume the crown. Dismissing relatively recent history known to Thutmose III of another woman who was king, Sobekneferu of Egypt's Middle Kingdom, she conjectured further that he might have thought that while she had enjoyed a short, approximately four-year reign, she ruled "at the very end of a fading [12th dynasty] Dynasty, and from the very start of her reign the odds had been stacked against her. She was, therefore, acceptable to conservative Egyptians as a patriotic 'Warrior Queen' who had failed" to rejuvenate Egypt's fortunes. In contrast, Hatshepsut's glorious reign was a completely different case: she demonstrated that women were as capable as men of ruling the two lands since she successfully presided over a prosperous Egypt for more than two decades. If Thutmose III's intent was to forestall the possibility of a woman assuming the throne, as proposed by Tyldesley, it was a failure since Twosret and Neferneferuaten (possibly), a female co-regent or successor of Akhenaten, assumed the throne for short reigns as pharaoh later in the New Kingdom.