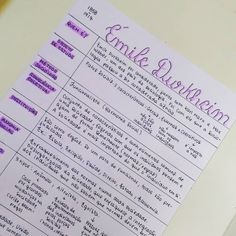

| Who is it? | Sociologist & Philosopher |

| Birth Day | April 15, 1858 |

| Birth Place | Épinal, French |

| Age | 161 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 15, 1917(1917-11-15) (aged 59)\nParis, Île-de-France, France |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure |

| Known for | Sacred–profane dichotomy Collective consciousness Social fact Social integration Anomie Collective effervescence |

| Fields | Philosophy, sociology, education, anthropology, religious studies |

| Institutions | University of Paris, University of Bordeaux |

| Influences | Immanuel Kant, René Descartes, Plato, Herbert Spencer, Aristotle, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Auguste Comte. William James, John Dewey, Fustel de Coulanges, John Stuart Mill |

| Influenced | Marcel Mauss, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Talcott Parsons, Maurice Halbwachs, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, Bronisław Malinowski, Fernand Braudel, Pierre Bourdieu, Charles Taylor, Henri Bergson, Emmanuel Levinas, Steven Lukes, Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Mary Douglas, Paul Fauconnet, Robert Bellah, Ziya Gökalp, David Bloor, Randall Collins, Jonathan Haidt |

Emile Durkheim, a renowned French sociologist and philosopher, is estimated to have a net worth between $100K to $1M in 2025. Despite his significant contributions to the field of sociology and philosophy, Durkheim's financial worth may seem modest compared to some contemporary figures. However, monetary value does not fully encapsulate the impact and intellectual legacy left by Durkheim. His groundbreaking theories on social integration and structural functionalism continue to shape and influence sociological discourse. Emile Durkheim's intellectual contributions have far surpassed any monetary quantification, solidifying his place as one of the most influential sociologists of all time.

For if society lacks the unity that derives from the fact that the relationships between its parts are exactly regulated, that unity resulting from the harmonious articulation of its various functions assured by effective discipline and if, in addition, society lacks the unity based upon the commitment of men's wills to a common objective, then it is no more than a pile of sand that the least jolt or the slightest puff will suffice to scatter.

— Émile Durkheim

A precocious student, Durkheim entered the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in 1879, at his third attempt. The entering class that year was one of the most brilliant of the nineteenth century and many of his classmates, such as Jean Jaurès and Henri Bergson, would go on to become major figures in France's intellectual history. At the ENS, Durkheim studied under the direction of Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, a classicist with a social scientific outlook, and wrote his Latin dissertation on Montesquieu. At the same time, he read Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. Thus Durkheim became interested in a scientific approach to society very early on in his career. This meant the first of many conflicts with the French academic system, which had no social science curriculum at the time. Durkheim found humanistic studies uninteresting, turning his attention from psychology and philosophy to ethics and eventually, sociology. He obtained his agrégation in philosophy in 1882, though finishing next to last in his graduating class owing to serious illness the year before.

The opportunity for Durkheim to a receive major academic appointment in Paris was inhibited by his approach to society. From 1882 to 1887 he taught philosophy at several provincial schools. In 1885 he decided to leave for Germany, where for two years he studied sociology at the universities of Marburg, Berlin and Leipzig. As Durkheim indicated in several essays, it was in Leipzig that he learned to appreciate the value of empiricism and its language of concrete, complex things, in sharp contrast to the more abstract, clear and simple ideas of the Cartesian method. By 1886, as part of his doctoral dissertation, he had completed the draft of his The Division of Labour in Society, and was working towards establishing the new science of sociology.

Also in 1887, Durkheim married Louise Dreyfus. They would have two children, Marie and André.

The 1890s were a period of remarkable creative output for Durkheim. In 1893, he published The Division of Labour in Society, his doctoral dissertation and fundamental statement of the nature of human society and its development. Durkheim's interest in social phenomena was spurred on by politics. France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War led to the fall of the regime of Napoleon III, which was then replaced by the Third Republic. This in turn resulted in a backlash against the new secular and republican rule, as many people considered a vigorously nationalistic approach necessary to rejuvenate France's fading power. Durkheim, a Jew and a staunch supporter of the Third Republic with a sympathy towards socialism, was thus in the political minority, a situation that galvanized him politically. The Dreyfus affair of 1894 only strengthened his Activist stance.

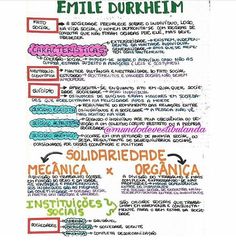

Much of Durkheim's work was concerned with how societies could maintain their integrity and coherence in modernity; an era in which traditional social and religious ties are no longer assumed, and in which new social institutions have come into being. His first major sociological work was The Division of Labour in Society (1893). In 1895, he published The Rules of Sociological Method and set up the first European department of sociology, becoming France's first professor of sociology. In 1898, he established the journal L'Année Sociologique. Durkheim's seminal monograph, Suicide (1897), a study of suicide rates in Catholic and Protestant populations, pioneered modern social research and served to distinguish social science from psychology and political philosophy. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912) presented a theory of religion, comparing the social and cultural lives of aboriginal and modern societies.

In The Rules of Sociological Method (1895), Durkheim expressed his will to establish a method that would guarantee sociology's truly scientific character. One of the questions raised by the author concerns the objectivity of the sociologist: how may one study an object that, from the very beginning, conditions and relates to the observer? According to Durkheim, observation must be as impartial and impersonal as possible, even though a "perfectly objective observation" in this sense may never be attained. A social fact must always be studied according to its relation with other social facts, never according to the individual who studies it. Sociology should therefore privilege comparison rather than the study of singular independent facts.

In Suicide (1897), Durkheim explores the differing suicide rates among Protestants and Catholics, arguing that stronger social control among Catholics results in lower suicide rates. According to Durkheim, Catholic society has normal levels of integration while Protestant society has low levels. Overall, Durkheim treated suicide as a social fact, explaining variations in its rate on a macro level, considering society-scale phenomena such as lack of connections between people (group attachment) and lack of regulations of behavior, rather than individuals' feelings and motivations.

While publishing short articles on the subject earlier in his career (for Example the essay De quelques formes primitives de classification written in 1902 with Marcel Mauss), Durkheim's definitive statement concerning the sociology of knowledge comes in his 1912 magnum opus The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. This book has as its goal not only the elucidation of the social origins and function of religion, but also the social origins and impact of society on language and logical thought. Durkheim worked largely out of a Kantian framework and sought to understand how the concepts and categories of logical thought could arise out of social life. He argued, for Example, that the categories of space and time were not a priori. Rather, the category of space depends on a society's social grouping and geographical use of space, and a group's social rhythm that determines our understanding of time. In this Durkheim sought to combine elements of rationalism and empiricism, arguing that certain aspects of logical thought Common to all humans did exist, but that they were products of collective life (thus contradicting the tabla rasa empiricist understanding whereby categories are acquired by individual experience alone), and that they were not universal a priori's (as Kant argued) since the content of the categories differed from society to society.

The outbreak of World War I was to have a tragic effect on Durkheim's life. His leftism was always patriotic rather than internationalist—he sought a secular, rational form of French life. But the coming of the war and the inevitable nationalist propaganda that followed made it difficult to sustain this already nuanced position. While Durkheim actively worked to support his country in the war, his reluctance to give in to simplistic nationalist fervor (combined with his Jewish background) made him a natural target of the now-ascendant French Right. Even more seriously, the generations of students that Durkheim had trained were now being drafted to serve in the army, and many of them perished in the trenches. Finally, Durkheim's own son, André, died on the war front in December 1915—a loss from which Durkheim never recovered. Emotionally devastated, Durkheim collapsed of a stroke in Paris on November 15, 1917. He was buried at the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

This study has been extensively discussed by later scholars and several major criticisms have emerged. First, Durkheim took most of his data from earlier researchers, notably Adolph Wagner and Henry Morselli, who were much more careful in generalizing from their own data. Second, later researchers found that the Protestant–Catholic differences in suicide seemed to be limited to German-speaking Europe and thus may have always been the spurious reflection of other factors. Durkheim's study of suicide has been criticized as an Example of the logical error termed the ecological fallacy. However, diverging views have contested whether Durkheim's work really contained an ecological fallacy. More recent authors such as Berk (2006) have also questioned the micro–macro relations underlying Durkheim's work. Some, such as Inkeles (1959), Johnson (1965) and Gibbs (1968), have claimed that Durkheim's only intent was to explain suicide sociologically within a holistic perspective, emphasizing that "he intended his theory to explain variation among social environments in the incidence of suicide, not the suicides of particular individuals".

In this definition, Durkheim avoids references to supernatural or God. Durkheim argued that the concept of supernatural is relatively new, tied to the development of science and separation of supernatural—that which cannot be rationally explained—from natural, that which can. Thus, according to Durkheim, for early humans, everything was supernatural. Similarly, he points out that religions that give little importance to the concept of god exist, such as Buddhism, where the Four Noble Truths are much more important than any individual deity. With that, Durkheim argues, we are left with the following three concepts: the sacred (the ideas that cannot be properly explained, inspire awe and are considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion), the beliefs and practices (which create highly emotional state—collective effervescence—and invest symbols with sacred importance), and the moral community (a group of people sharing a Common moral philosophy). Out of those three concepts, Durkheim focused on the sacred, noting that it is at the very core of a religion. He defined sacred things as:

Much of Durkheim's work, however, remains unacknowledged in philosophy, despite its direct relevance. As proof one can look to John Searle, who wrote a book The Construction of Social Reality, in which he elaborates a theory of social facts and collective representations that he believed to be a landmark work that would bridge the gap between analytic and continental philosophy. Neil Gross however, demonstrates how Searle's views on society are more or less a reconstitution of Durkheim's theories of social facts, social institutions, collective representations and the like. Searle's ideas are thus open to the same criticisms as Durkheim's. Searle responded by saying that Durkheim's work was worse than he had originally believed, and, admitting that he had not read much of Durkheim's work, said that, "Because Durkheim’s account seemed so impoverished I did not read any further in his work." Stephen Lukes, however, responded to Searle's response to Gross and refutes point by point the allegations that Searle makes against Durkheim, essentially upholding the argument of Gross, that Searle's work bears great resemblance to that of Durkheim's. Lukes attributes Searle's miscomprehension of Durkheim's work to the fact that Searle, quite simply, never read Durkheim.