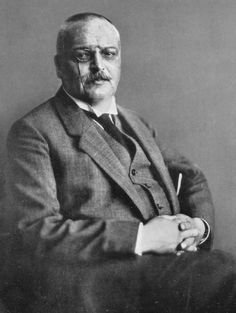

| Who is it? | Psychiatrist |

| Birth Day | February 15, 1856 |

| Birth Place | Neustrelitz, German |

| Age | 163 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 7 October 1926(1926-10-07) (aged 70)\nMunich, Germany |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Alma mater | Leipzig University University of Würzburg (MBBS, 1878) University of Munich (Dr. hab. med., 1882) |

| Known for | Classification of mental disorders, Kraepelinian dichotomy |

| Spouse(s) | Ina Marie Marie Wilhelmine Schwabe |

| Children | 2 sons, 6 daughters |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

| Institutions | University of Dorpat University of Heidelberg University of Munich |

| Thesis | The Place of Psychology in Psychiatry (1882) |

| Influences | Wilhelm Wundt Bernhard von Gudden Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum |

| Influenced | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems |

Emil Kraepelin, a renowned German psychiatrist, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in the year 2025. Throughout his career, Kraepelin made significant contributions to the field of psychiatry, particularly in the diagnosis and classification of mental disorders. His groundbreaking research laid the foundation for the modern understanding of various psychiatric conditions. Despite the challenges faced by psychiatrists of his time, Kraepelin's expertise and dedication propelled him to become one of the leading figures in the field. Today, his legacy lives on as his work continues to shape the way mental illnesses are understood and treated.

Kraepelin, whose father, Karl Wilhelm, was a former opera singer, music Teacher, and later successful story Teller, was born in 1856 in Neustrelitz, in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz in Germany. He was first introduced to biology by his brother Karl, 10 years older and, later, the Director of the Zoological Museum of Hamburg.

Kraepelin began his medical studies in 1874 at the University of Leipzig and completed them at the University of Würzburg (1877–78). At Leipzig, he studied neuropathology under Paul Flechsig and experimental psychology with Wilhelm Wundt. Kraepelin would be a disciple of Wundt and had a lifelong interest in experimental psychology based on his theories. While there, Kraepelin wrote a prize-winning essay, "The Influence of Acute Illness in the Causation of Mental Disorders". At Würzburg he completed his Rigorosum (roughly equivalent to an MBBS viva-voce examination) in March 1878, his Staatsexamen (licensing examination) in July 1878, and his Approbation (his license to practice medicine; roughly equivalent to an MBBS) on 9 August 1878. From August 1878 to 1882, he worked with Bernhard von Gudden at the University of Munich. Returning to the University of Leipzig in February 1882, he worked in Wilhelm Heinrich Erb's neurology clinic and in Wundt's psychopharmacology laboratory. He completed his Habilitation thesis at Leipzig; it was entitled "The Place of Psychology in Psychiatry". On 3 December 1883 he completed his Umhabilitierung (de) (habilitation recognition procedure) at Munich.

Kraepelin's major work, Compendium der Psychiatrie: Zum Gebrauche für Studirende und Aertze (Compendium of Psychiatry: For the Use of Students and Physicians), was first published in 1883 and was expanded in subsequent multivolume editions to Ein Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie (A Textbook: Foundations of Psychiatry and Neuroscience). In it, he argued that psychiatry was a branch of medical science and should be investigated by observation and experimentation like the other natural sciences. He called for research into the physical causes of mental illness, and started to establish the foundations of the modern classification system for mental disorders. Kraepelin proposed that by studying case histories and identifying specific disorders, the progression of mental illness could be predicted, after taking into account individual differences in personality and patient age at the onset of disease.

In 1884 he became senior physician in the Prussian provincial town of Leubus, Silesia Province, and the following year he was appointed Director of the Treatment and Nursing Institute in Dresden. On 1 July 1886, at the age of 30, Kraepelin was named Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Dorpat (today the University of Tartu) in what is today Estonia (see Burgmair et al., vol. IV). Four years later, on 5 December 1890, he became department head at the University of Heidelberg, where he remained until 1904. While at Dorpat he became the Director of the 80-bed University Clinic. There he began to study and record many clinical histories in detail and "was led to consider the importance of the course of the illness with regard to the classification of mental disorders".

Drawing on his long-term research, and using the criteria of course, outcome and prognosis, he developed the concept of dementia praecox, which he defined as the "sub-acute development of a peculiar simple condition of mental weakness occurring at a youthful age". When he first introduced this concept as a diagnostic entity in the fourth German edition of his Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie in 1893, it was placed among the degenerative disorders alongside, but separate from, catatonia and dementia paranoides. At that time, the concept corresponded by and large with Ewald Hecker's hebephrenia. In the sixth edition of the Lehrbuch in 1899 all three of these clinical types are treated as different expressions of one disease, dementia praecox.

Kraepelin had referred to psychopathic conditions (or "states") in his 1896 edition, including compulsive insanity, impulsive insanity, homosexuality, and mood disturbances. From 1904, however, he instead termed those "original disease conditions, and introduced the new alternative category of psychopathic personalities. In the eighth edition from 1909 that category would include, in addition to a separate "dissocial" type, the excitable, the unstable, the Triebmenschen driven persons, eccentrics, the liars and swindlers, and the quarrelsome. It has been described as remarkable that Kraepelin now considered mood disturbances to be not part of the same category, but only attenuated (more mild) phases of manic depressive illness; this corresponds to current classification schemes.

Kraepelin wrote in a knapp und klar (concise and clear) style that made his books useful tools for Physicians. Abridged and clumsy English translations of the sixth and seventh editions of his textbook in 1902 and 1907 (respectively) by Allan Ross Diefendorf (1871–1943), an assistant physician at the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane at Middletown, inadequately conveyed the literary quality of his writings that made them so valuable to practitioners.

Upon moving to become Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at the University of Munich in 1903, Kraepelin increasingly wrote on social policy issues. He was a strong and influential proponent of eugenics and racial hygiene. His publications included a focus on alcoholism, crime, degeneration and hysteria. Kraepelin was convinced that such institutions as the education system and the welfare state, because of their trend to break the processes of natural selection, undermined the Germans’ biological "struggle for survival". He was concerned to preserve and enhance the German people, the Volk, in the sense of nation or race. He appears to have held Lamarckian concepts of evolution, such that cultural deterioration could be inherited. He was a strong ally and promoter of the work of fellow Psychiatrist (and pupil and later successor as Director of the clinic) Ernst Rudin to clarify the mechanisms of genetic inheritance as to make a so-called "empirical genetic prognosis".

In fact from 1904 Kraepelin changed the section heading to "The born criminal", moving it from under "Congenital feeble-mindedness" to a new chapter on "Psychopathic personalities". They were treated under a theory of degeneration. Four types were distinguished: born Criminals (inborn delinquents), pathological liars, querulous persons, and Triebmenschen (persons driven by a basic compulsion, including vagabonds, spendthrifts, and dipsomaniacs). The concept of "psychopathic inferiorities" had been recently popularised in Germany by Julius Ludwig August Koch, who proposed congenital and acquired types. Kraepelin had no evidence or explanation suggesting a congenital cause, and his assumption therefore appears to have been simple "biologism". Others, such as Gustav Aschaffenburg, argued for a varying combination of causes. Kraepelin's assumption of a moral defect rather than a positive drive towards crime has also been questioned, as it implies that the moral sense is somehow inborn and unvarying, yet it was known to vary by time and place, and Kraepelin never considered that the moral sense might just be different. Kurt Schneider criticized Kraepelin's nosology for appearing to be a list of behaviors that he considered undesirable, rather than medical conditions, though Schneider's alternative version has also been criticised on the same basis. Nevertheless, many essentials of these diagnostic systems were introduced into the diagnostic systems, and remarkable similarities remain in the DSM-IV and ICD-10. The issues would today mainly be considered under the category of personality disorders, or in terms of Kraepelin's focus on psychopathy.

He was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1908.

In 1912 at the request of the German Society of Psychiatry, he began plans to establish a centre for research. Following a large donation from the Jewish German-American banker James Loeb, who had at one time been a patient, and promises of support from "patrons of science", the German Institute for Psychiatric Research was founded in 1917 in Munich. Initially housed in existing hospital buildings, it was maintained by further donations from Loeb and his relatives. In 1924 it came under the auspices of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science. The German American Rockefeller family's Rockefeller Foundation made a large donation enabling the development of a new dedicated building for the institute, along Kraepelin's guidelines, which was officially opened in 1928.

In addition, as Kraepelin accepted in 1920, "It is becoming increasingly obvious that we cannot satisfactorily distinguish these two diseases"; however, he maintained that "On the one hand we find those patients with irreversible dementia and severe cortical lesions. On the other are those patients whose personality remains intact". Nevertheless, overlap between the diagnoses and neurological abnormalities (when found) have continued, and in fact a diagnostic category of schizoaffective disorder would be brought in to cover the intermediate cases.

Kraepelin retired from teaching at the age of 66, spending his remaining years establishing the Institute. The ninth and final edition of his Textbook was published in 1927, shortly after his death. It comprised four volumes and was ten times larger than the first edition of 1883.

Kraepelin announced that he had found a new way of looking at mental illness, referring to the traditional view as "symptomatic" and to his view as "clinical". This turned out to be his paradigm-setting synthesis of the hundreds of mental disorders Classified by the 19th century, grouping diseases together based on classification of syndrome—common patterns of symptoms over time—rather than by simple similarity of major symptoms in the manner of his predecessors. Kraepelin described his work in the 5th edition of his textbook as a "decisive step from a symptomatic to a clinical view of insanity. . . . The importance of external clinical signs has . . . been subordinated to consideration of the conditions of origin, the course, and the terminus which result from individual disorders. Thus, all purely symptomatic categories have disappeared from the nosology".