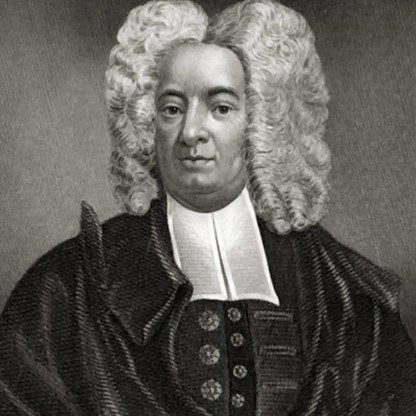

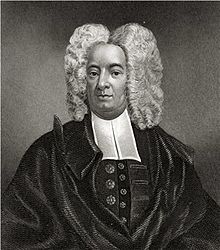

| Who is it? | Church Minister |

| Birth Day | February 12, 1663 |

| Birth Place | Boston, United States |

| Age | 356 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | February 13, 1728(1728-02-13) (aged 65)\nProvince of Massachusetts Bay |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Alma mater | Harvard College |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Parent(s) | Increase Mather and Maria Cotton |

| Relatives | John Cotton and Richard Mather |

Cotton Mather, a renowned church minister in the United States, is projected to have a remarkable net worth of $17 million in 2025. Recognized for his influential role in shaping the spiritual landscape of the country, Mather has garnered significant wealth throughout his career. His theological prowess and captivating sermons have attracted a devoted following, leading to lucrative speaking engagements, book deals, and widespread support from his congregation. Mather's dedication to his ministry has not only brought spiritual enrichment to many lives but has also contributed to his impressive financial success.

Few puritans more loudly decried the bosom serpent of egotism than did Cotton Mather; none more clearly exemplified it. Explicitly or implicitly, he projects himself everywhere in his writings. In the most direct compensatory sense, he does so by using literature as a means of personal redress. He tells us that he composed his discussions of the family to bless his own, his essays on the riches of Christ to repay his benefactors, his tracts on morality to convert his enemies, his funeral discourses to console himself for the loss of a child, wife, or friend.

Smallpox was a serious threat in colonial America, most devastating to Native Americans, but also to Anglo-American settlers. New England suffered smallpox epidemics in 1677, 1689–90, and 1702. It was highly contagious, and mortality could reach as high as 30 percent. Boston had been plagued by smallpox outbreaks in 1690 and 1702. During this era, public authorities in Massachusetts dealt with the threat primarily by means of quarantine. Incoming ships were quarantined in Boston harbor, and any smallpox patients in town were held under guard or in a "pesthouse".

Mather was born in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, the son of Maria (née Cotton) and Increase Mather, and grandson of both John Cotton and Richard Mather, all also prominent Puritan ministers. Mather was named after his maternal grandfather John Cotton. He attended Boston Latin School, where his name was posthumously added to its Hall of Fame, and graduated from Harvard in 1678 at age 15. After completing his post-graduate work, he joined his father as assistant pastor of Boston's original North Church (not to be confused with the Anglican/Episcopal Old North Church of Paul Revere fame). In 1685, Mather assumed full responsibilities as pastor of the church.

Robert Boyle was a huge influence throughout Mather's career. He read Boyle's The Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy closely throughout the 1680s, and his own early works on science and religion borrowed greatly from it, using almost identical language to Boyle.

Mather's first published sermon, printed in 1686, concerned the execution of James Morgan, convicted of murder. Thirteen years later, Mather published the sermon in a compilation, along with other similar works, called Pillars of Salt.

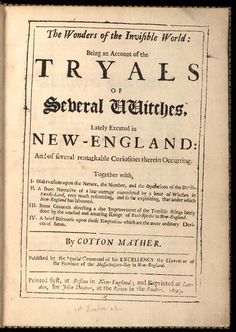

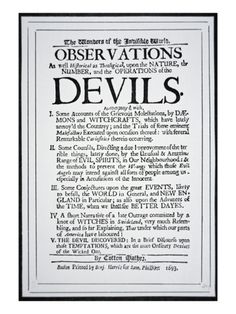

In 1689, Mather published Memorable Providences detailing the supposed afflictions of several children in the Goodwin family in Boston. Catholic washerwoman Goody Glover was convicted of witchcraft and executed in this case. Mather had a prominent role in this case. Besides praying for the children, which also included fasting and meditation, he would also observe and record their activities. The children were subject to hysterical fits, which he detailed in Memorable Providences. In his book, Mather argued that since there are witches and devils, there are "immortal souls." He also claimed that witches appear spectrally as themselves. He opposed any natural explanations for the fits, he believed that people who confessed to using witchcraft were sane, he warned against performing magic due to its connection with the devil and he argued that spectral evidence should not be used as evidence for witchcraft. Robert Calef was a contemporary of Mather and critical of him, and he considered this book responsible for laying the groundwork for the Salem witch trials three years later:

Upham's book refers to Robert Calef no fewer than 25 times with the majority of these regarding documents compiled by Calef in the mid-1690s and stating: "Although zealously devoted to the work of exposing the enormities connected with the witchcraft prosecutions, there is no ground to dispute the veracity of Calef as to matters of fact." He goes on to say that Calef's collection of writings "gave a shock to Mather's influence, from which it never recovered."

Toward the later half of the twentieth century, a number of historians at universities far from New England seemed to find inspiration in the Kittredge lineage. In Selected Letters of Cotton Mather Ken Silverman writes, "Actually, Mather had very little to do with the trials." Twelve pages later Silverman publishes, for the first time, a letter to chief judge william Stoughton on September 2, 1692, in which Cotton Mather writes "… I hope I can may say that one half of my endeavors to serve you have not been told or seen … I have labored to divert the thoughts of my readers with something of a designed contrivance…" Writing in the early 1980s, Historian John Demos imputed to Mather a purportedly moderating influence on the trials.

When Mather died, he left behind an abundance of unfinished writings, including one entitled The Biblia Americana. Mather believed that Biblia Americana was the best thing he had ever written; his masterwork. Biblia Americana contained Mather's thoughts and opinions on the Bible and how he interpreted it. Biblia Americana is incredibly large, and Mather worked on it from 1693 until 1728, when he died. Mather tried to convince others that philosophy and science could work together with religion instead of against it. People did not have to choose one or the other. In Biblia Americana, Mather looked at the Bible through a scientific perspective, completely opposite to his perspective in The Christian Philosopher, in which he approached science in a religious manner.

Thomas Hutchinson summarized the Return, "The two first and the last sections of this advice took away the force of all the others, and the prosecutions went on with more vigor than before." Reprinting the Return five years later in his anonymously published Life of Phips (1697), Cotton Mather omitted the fateful "two first and the last" sections, though they were the ones he had already given most attention in his "Wonders of the Invisible World" rushed into publication in the summer and early autumn of 1692.

With the smallpox epidemic catching speed and racking up a staggering death toll, a solution to the crisis was becoming more urgently needed by the day. The use of quarantine and various other efforts, such as balancing the body's humors, did not slow the spread of the disease. As news rolled in from town to town and correspondence arrived from overseas, reports of horrific stories of suffering and loss due to smallpox stirred mass panic among the people. "By circa 1700, smallpox had become among the most devastating of epidemic diseases circulating in the Atlantic world."

Magnalia Christi Americana, considered Mather's greatest work, was published in 1702, when he was 39. The book includes several biographies of saints and describes the process of the New England settlement. In this context "saints" does not refer to the canonized saints of the Catholic church, but to those Puritan divines about whom Mather is writing. It comprises seven total books, including Pietas in Patriam: The life of His Excellency Sir william Phips, originally published anonymously in London in 1697. Despite being one of Mather's best-known works, many have openly criticized it, labeling it as hard to follow and understand, and poorly paced and organized. However, other critics have praised Mather's work, citing it as one of the best efforts at properly documenting the establishment of America and growth of the people.

In 1706, Mather's slave, Onesimus, explained to Mather how he had been inoculated as a child in Africa. Mather was fascinated by the idea. By July 1716, he had read an endorsement of inoculation by Dr Emanuel Timonius of Constantinople in the Philosophical Transactions. Mather then declared, in a letter to Dr John Woodward of Gresham College in London, that he planned to press Boston's doctors to adopt the practice of inoculation should smallpox reach the colony again.

The practice of smallpox inoculation (as opposed to the later practice of vaccination) was developed possibly in 8th-century India or 10th-century China. Spreading its reach in seventeenth-century Turkey, inoculation or, rather, variolation, involved infecting a person via a cut in the skin with exudate from a patient with a relatively mild case of smallpox (variola), to bring about a manageable and recoverable infection that would provide later immunity. By the beginning of the 18th century, the Royal Society in England was discussing the practice of inoculation, and the smallpox epidemic in 1713 spurred further interest. It was not until 1721, however, that England recorded its first case of inoculation.

Mather influenced early American science. In 1716, he conducted one of the first recorded experiments with plant hybridization because of observations of corn varieties. This observation was memorialized in a letter to his friend James Petiver:

In 1721, Mather published The Christian Philosopher, the first systematic book on science published in America. Mather attempted to show how Newtonian science and religion were in harmony. It was in part based on Robert Boyle's The Christian Virtuoso (1690). Mather reportedly took inspiration from Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, by the 12th-century Islamic Philosopher Abu Bakr Ibn Tufail.

In 1869, william Frederick Poole quoted from various school textbooks of the time demonstrating they were in agreement on Cotton Mather's role in the Witch Trials:

Evidenced by the published opinion in the years that followed the Poole vs Upham debate, it would seem Upham was considered the clear winner (see Sibley, GH Moore, WC Ford, and GH Burr below.). In 1891, Harvard English professor Barrett Wendall wrote Cotton Mather, The Puritan Priest. His book often expresses agreement with Upham but also announces an intention to show Cotton Mather in a more positive light. "[Cotton Mather] gave utterance to many hasty things not always consistent with fact or with each other…" And some pages later: "[Robert] Calef’s temper was that of the rational Eighteenth century; the Mathers belonged rather to the Sixteenth, the age of passionate religious enthusiasm."

In 1907, George Lyman Kittredge published an essay that would become foundational to a major change in the 20th-century view of witchcraft and Mather culpability therein. Kittredge is dismissive of Robert Calef, and sarcastic toward Upham, but shows a fondness for Poole and a similar soft touch toward Cotton Mather. Responding to Kittredge in 1911, George Lincoln Burr, a Historian at Cornell, published an essay that begins in a professional and friendly fashion toward both Poole and Kittredge, but quickly becomes a passionate and direct criticism, stating that Kittredge in the "zeal of his apology… reached results so startlingly new, so contradictory of what my own lifelong study in this field has seemed to teach, so unconfirmed by further research… and withal so much more generous to our ancestors than I can find it in my conscience to deem fair, that I should be less than honest did I not seize this earliest opportunity share with you the reasons for my doubts…" (In referring to "ancestors" Burr primarily means the Mathers, as is made clear in the substance of the essay.) The final paragraph of Burr's 1911 essay pushes these men's debate into the realm of a progressive creed

Perhaps as a continuation of his argument, in 1914, George Lincoln Burr published a large compilation "Narratives". This book arguably continues to be the single most cited reference on the subject. Unlike Poole and Upham, Burr avoids forwarding his previous debate with Kittredge directly into his book and mentions Kittredge only once, briefly in a footnote citing both of their essays from 1907 and 1911, but without further comment. But in addition to the viewpoint displayed by Burr's selections, he weighs in on the Poole vs Upham debate at various times, including siding with Upham in a note on Thomas Brattle's letter, "The strange suggestion of W. F. Poole that Brattle here means Cotton Mather himself, is adequately answered by Upham…" Burr's "Narratives" reprint a lengthy but abridged portion of Calef's book and introducing it he digs deep into the historical record for information on Calef and concludes "…that he had else any grievance against the Mathers or their colleagues there is no reason to think." Burr finds that a comparison between Calef's work and original documents in the historical record collections "testify to the care and exactness…"

Coinciding with the tercentary of the trials in 1992, there was a flurry of publications.

Puritans found meaning in affliction, and they did not yet know why God was showing them disfavor through smallpox. Not to address their errant ways before attempting a cure could set them back in their "errand". Many Puritans believed that creating a wound and inserting poison was doing violence and therefore was antithetical to the healing art. They grappled with adhering to the Ten Commandments, with being proper church members and good caring neighbors. The apparent contradiction between harming or murdering a neighbor through inoculation and the Sixth Commandment—"thou shalt not kill"—seemed insoluble and hence stood as one of the main objections against the procedure. Williams maintained that because the subject of inoculation could not be found in the Bible, it was not the will of God, and therefore "unlawful." He explained that inoculation violated The Golden Rule, because if one neighbor voluntarily infected another with disease, he was not doing unto others as he would have done to him. With the Bible as the Puritans' source for all decision-making, lack of scriptural evidence concerned many, and Williams vocally scorned Mather for not being able to reference an inoculation edict directly from the Bible.