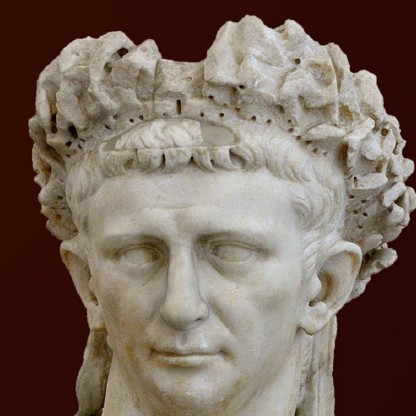

| Who is it? | Roman emperor |

| Birth Place | Lyon, Ancient Roman |

| Died On | 13 October 54 AD (age 63)\nRome, Italy |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Reign | 24 January 41 – 13 October 54 (13 years) |

| Predecessor | Caligula |

| Successor | Nero |

| Burial | Mausoleum of Augustus |

| Spouse | Plautia Urgulanilla Aelia Paetina Valeria Messalina Agrippina the Younger (niece) |

| Issue | Claudius Drusus Claudia Antonia Claudia Octavia Britannicus Nero (adoptive) |

| Full name | Full name (at birth) Tiberius Claudius Drusus (later) Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus (by death) Ti. Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (at birth) Tiberius Claudius Drusus (later) Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus (by death) Ti. Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus |

| Imperial Dynasty | Julio-Claudian |

| Father | Nero Claudius Drusus |

| Mother | Antonia Minor |

| Religion | ancient Roman religion |

Claudius, the Roman emperor of Ancient Rome, has amassed an impressive net worth of approximately $11 million by 2025. His financial success can be attributed to his strategic management of the Roman Empire's resources and his ability to maintain peace and stability during his reign. This considerable wealth allowed Claudius to expand the empire's territories, invest in infrastructure development, and foster economic growth. As a prominent figure in history, Claudius' net worth reflects his influential role in shaping the ancient world.

If you accept these proposals, Conscript Fathers, say so at once and simply, in accordance with your convictions. If you do not accept them, find alternatives, but do so here and now; or if you wish to take time for consideration, take it, provided you do not forget that you must be ready to pronounce your opinion whenever you may be summoned to meet. It ill befits the dignity of the Senate that the consul designate should repeat the phrases of the consuls word for word as his opinion, and that every one else should merely say 'I approve', and that then, after leaving, the assembly should announce 'We debated'.

Modern assessments of his health have changed several times in the past century. Prior to World War II, infantile paralysis (or polio) was widely accepted as the cause. This is the diagnosis used in Robert Graves' Claudius novels, first published in the 1930s. Polio does not explain many of the described symptoms, however, and a more recent theory implicates cerebral palsy as the cause, as outlined by Ernestine Leon. Tourette syndrome has also been considered a possibility.

Soon after (possibly in 28), Claudius married Aelia Paetina, a relative of Sejanus, if not Sejanus's adoptive sister. During their marriage, Claudius and Paetina had a daughter, Claudia Antonia. He later divorced her after the marriage became a political liability, although Leon (1948) suggests it may have been due to emotional and mental abuse by Paetina.

Claudius organised a performance of the Secular Games, marking the 800th anniversary of the founding of Rome. Augustus had performed the same games less than a century prior. Augustus' excuse was that the interval for the games was 110 years, not 100, but his date actually did not qualify under either reasoning. Claudius also presented naval battles to mark the attempted draining of the Fucine Lake, as well as many other public games and shows.

However, as the Flavians became established, they needed to emphasize their own credentials more, and their references to Claudius ceased. Instead, he was lumped with the other emperors of the fallen dynasty. His state cult in Rome probably continued until the abolition of all such cults of dead Emperors by Maximinus Thrax in 237–238. The Feriale Duranum, probably identical to the festival calendars of every regular army unit, assigns him a sacrifice of a steer on his birthday, the Kalends of August. And such commemoration (and consequent feasting) probably continued until the Christianization and disintegration of the army in the late 4th century.

Agrippina had sent away Narcissus shortly before Claudius' death, and now murdered the freedman. The last act of this secretary of letters was to burn all of Claudius' correspondence — most likely so it could not be used against him and others in an already hostile new regime. Thus Claudius' private words about his own policies and motives were lost to history. Just as Claudius had criticized his predecessors in official edicts (see below), Nero often criticized the deceased Emperor and many of Claudius' laws and edicts were disregarded under the reasoning that he was too stupid and senile to have meant them.

The last part of Claudius' plan was to increase the amount of arable land in Italy. This was to be achieved by draining the Fucine lake, which would have the added benefit of making the nearby river navigable year-round. A tunnel was dug through the lake bed, but the plan was a failure. The tunnel was crooked and not large enough to carry the water, which caused it to back up when opened. The resultant flood washed out a large gladiatorial exhibition held to commemorate the opening, causing Claudius to run for his life along with the other spectators. The draining of the lake continued to present a Problem well into the Middle Ages. It was finally achieved by the Prince Torlonia in the 19th century, producing over 160,000 acres (650 km) of new arable land. He expanded the Claudian tunnel to three times its original size.