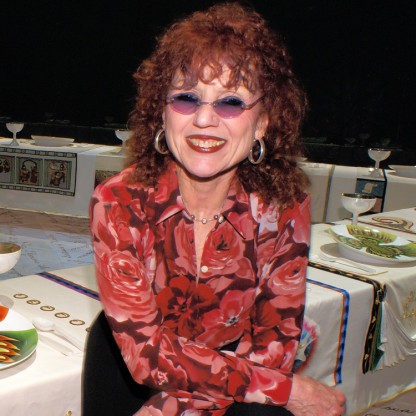

| Who is it? | Painter, Sculptor, Artist, Muralist, Teacher |

| Birth Day | November 28, 1907 |

| Birth Place | Charlotte, United States |

| Age | 113 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | April 27, 1977(1977-04-27) (aged 69)\nNew York City |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Education | Columbia University, Teachers College |

| Known for | Muralism, Painting, Illustration, Sculpture |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism |

| Patron(s) | Lemoine Pierce |

Charles Alston, a renowned painter, sculptor, artist, muralist, and teacher in the United States, is expected to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2025. Alston's exceptional talent and dedication to his craft have earned him recognition and success throughout his career. With his diverse artistic skills, he has left an indelible mark in the world of art, captivating audiences with his unique creations. Additionally, Alston's notable contributions as a teacher have influenced and inspired countless aspiring artists. With such a wide range of expertise and accomplishments, it is no wonder that his net worth is estimated to be substantial in the coming years.

Charles Henry Alston was born on November 28, 1907, in Charlotte, North Carolina, to Reverend Primus Priss Alston and Anna Elizabeth Miller Alston, and was the youngest of five children. Only three survived past infancy: Charles, his sister Rousmaniere and his brother Wendell. His father was born into slavery in 1851 in Pittsboro, North Carolina; after the Civil War, he graduated from St. Augustine's College and became a prominent minister and founder of St. Michael's Episcopal Church. He was described as a "race man": an African American who dedicated his skills to the furtherance of the black race. Reverend Alston met his wife when she was a student at his school. Charles was nicknamed "Spinky" by his father, and kept the nickname as an adult. In 1910, when Charles was three, his father died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage. Locals described him in admiration as the "Booker T. Washington of Charlotte".

In 1913 Anna Alston married Harry Bearden. Through the marriage, the Future Artist Romare Bearden became Charles’ cousin. The two Bearden families lived across the street from each other; the friendship between Romare and Charles would last a lifetime. As a child Alston was inspired by his older brother Wendell's drawings of trains and cars, which the young Artist copied. Charles also played with clay, creating a sculpture of North Carolina. As an adult he reflected on his memories of sculpting with clay as a child: "I’d get buckets of it and put it through strainers and make things out of it. I think that's the first art experience I remember, making things." His mother was a skilled embroiderer and took up painting at the age of 75. His father was also good at drawing, wooing Alston's mother with small sketches in the medians of letters he wrote her.

In 1915 the family moved to New York, as many African-American families did during the Great Migration. Alston's step-father, Henry Bearden, left before his wife and children to secure a job overseeing elevator operations and the newsstand staff at the Bretton Hotel in the Upper West Side. The family lived in Harlem and was considered middle-class. During the Great Depression, the people of Harlem suffered economically. The "stoic strength" seen within the community was later expressed in Charles’ fine art. At Public School 179 in Manhattan, the boy's artistic abilities were recognized and he was asked to draw all of the school posters during his years there.

Alston graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School, where he was nominated for academic excellence and was the art Editor of the school's magazine, The Magpie. He was a member of the Arista - National Honor Society and also studied drawing and anatomy at the Saturday school of the National Academy of Art . In high school he was given his first oil paints and learned about his aunt Bessye Bearden's art salons, which stars like Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes attended. After graduating in 1925, he attended Columbia University, turning down a scholarship to the Yale School of Fine Arts.

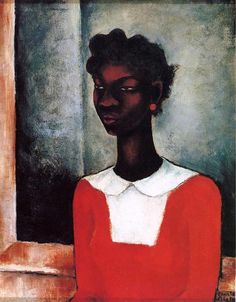

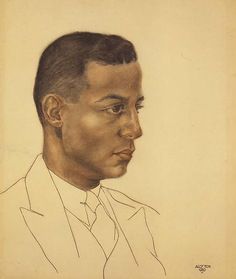

Alston shared studio space with Henry Bannarn at 306 W. 141st Street, which served as an open space for artists, Photographers, Musicians, Writers and the like. Other artists held studio space at 306, such as Jacob Lawrence, Addison Bate and his brother Leon. During this time Alston founded the Harlem Artists Guild with Savage and Elba Lightfoot to work towards equality in WPA art programs in New York. During the early years of 306, Alston focused on mastering portraiture. Early works such as Portrait of a Man (1929) show Alston's detailed and realistic style depicted through pastels and charcoals, inspired by the style of Winold Reiss. In his Girl in a Red Dress (1934) and The Blue Shirt (1935), he used modern and innovative techniques for his portraits of young individuals in Harlem. Blue Shirt is thought to be a portrait of Jacob Lawrence. During this time he also created Man Seated with Travel Bag (c. 1938–40), showing the seedy and bleak environment, contrasting with work like the racially charged Vaudeville (c. 1930) and its caricature style of a man in blackface.

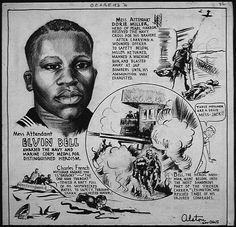

During the 1930s and early 1940s, Alston created illustrations for magazines such as Fortune, Mademoiselle, The New Yorker, Melody Maker and others. He also designed album covers for artists such as Duke Ellington and Coleman Hawkins. Alston became staff Artist at the Office of War Information and Public Relations in 1940, creating drawings of notable African Americans. These images were used in over 200 black newspapers across the country by the government to "foster goodwill with the black citizenry."

Originally hired as an easel Painter, in 1935 Alston became the first African-American supervisor to work for the WPA's Federal Art Project (FAP) in New York, which would also serve as his first mural work. At this time he was awarded WPA Project Number 1262 – an opportunity to oversee a group of artists creating murals and to supervise their painting for the Harlem Hospital. The first government commission ever awarded to African-American artists including Beauford Delaney, Seabrook Powell and Vertis Hayes. He also had the chance to create and paint his own contribution to the collection: Magic in Medicine and Modern Medicine. These paintings were part of a diptych completed in 1936 depicting the history of Medicine in the African-American community and Beauford Delaney served as assistant. When creating the murals Alston was inspired by the work of Aaron Douglas, who a year earlier had created the public art piece Aspects of Negro Life for the New York Public Library, and researched traditional African culture, including traditional African Medicine. Magic in Medicine, which depicts African culture and holistic healing, is considered one of "America's first public scenes of Africa". All of the murals sketches submitted were accepted by the FAP, however, four were denied creation by the hospital superintendent Lawrence T. Dermody and commissioner of hospitals S.S. Goldwater due to the excessive amount of African-American representation in the works. The artists fought the response through letter writing and four years later succeeded in gaining the right to complete the murals. The sketches for Magic in Medicine and Modern Medicine were exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art's "New Horizons in American Art".

In 1938 the Rosenwald Fund provided money for Alston to travel to the South, which was his first return there since leaving as a child. His travel with Giles Hubert, an inspector for the Farm Security Administration, gave him access to certain situations and he photographed many aspects of rural life. These photographs serves as the basis for a series of genre portraits depicting southern black life. In 1940 he completed Tobacco Farmer, the portrait of a young black farmer in white overalls and a blue shirt with a youthful yet serious look upon his face, sitting in front of the landscape and buildings he works on and in. That same year he received a second round of funding from the Rosenwald Fund to travel South, and he spent extended time at Atlanta University.

In the late 1940s Alston became involved in a mural project commissioned by Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company which asked the artists to create work involving African-American contributions to the settling of California. Alston worked with Hale Woodruff on the murals in a large studio space in New York where they utilized ladders to reach the upper parts of the canvas. The artworks, which are considered "priceless contributions to American narrative art", consists of two panels: Exploration and Colonization by Alston and Settlement and Development by Woodruff. Alston's piece covers the post-colonial period of 1527 to 1850. Images of James Beckwourth, Biddy Mason, and william Leidesdorff are portrayed in the well detailed historical mural. While both artists kept in contact with African Americans on the West Coast during its creation, influencing the content and depictions. The murals, which were unveiled in 1949, have been on display in the lobby of the Golden State Mutual Headquarters. Due to economic downturn Golden State was forced to sell their entire art collection to ward off its mounting debts and as of spring 2011 the National Museum of African American History and Culture had offered $750,000 to purchase the artworks which led to a controversy regarding the importance of the artworks which have been estimated to be worth at least $5 million. It was requested that the murals be covered by city landmark protections by the Los Angeles Conservancy. The state of California had declined philanthropic proposals to keep the murals in their original location and the Smithsonian withdrew their offer. The murals are currently awaiting their fate in California courts.

In the beginning Charles Alston's mural work was inspired by the work of Aaron Douglas, Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, the latter who he met when they did mural work in New York. In 1943 Alston was elected to the board of Directors of the National Society of Mural Painters. He created murals for the Harlem Hospital, Golden State Mutual, American Museum of Natural History, Public School 154, the Bronx Family and Criminal Court and the Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn, New York.

For the years 1942–43 Alston was stationed in the army at Fort Huachuca in Arizona. Upon returning to New York on April 8, 1944, he married Dr. Myra Adele Logan, then an intern at the Harlem Hospital. They met when he was working on a mural project at the hospital. Their home, including his studio, as on Edgecombe Avenue near Highbridge Park. The couple lived close to family; at their frequent gatherings Alston enjoyed cooking and Myra played piano. During the 1940s Alston also took occasional art classes studying under Alexander Kostellow.

Eventually Alston left commercial work to focus on his own artwork. In 1950, he became the first African-American instructor at the Art Students League, where he remained on faculty until 1971. In 1950, his Painting was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and his artwork was one of few purchased by the museum. He landed his first solo exhibition in 1953 at the John Heller Gallery, which represented artists such as Roy Lichtenstein. He exhibited there five times from 1953 to 1958.

In 1956, he became the first African-American instructor at the Museum of Modern Art, where he taught for a year before going to Belgium on behalf of MOMA and the State Department. He coordinated the children's community center at Expo 58. In 1958 he was awarded a grant from and was elected as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Alston also created sculptures. Head of a Woman (1957) shows his move towards a "reductive and modern approach to sculpture....where facial features were suggested rather than fully formulated in three dimensions,". In 1970 Alston was commissioned by the Community Church of New York to create a bust of Martin Luther King Jr. for $5,000, with only five copies produced. In 1990 Alston's bronze bust of Martin Luther King Jr. (1970), became the first image of an African American displayed in the White House.

Alston's murals were hung in the Women's Pavilion of the hospital over uncapped radiators which caused the paintings to deteriorate from the steam. Plans failed to recap the radiators. In 1959 Alston estimated, in a letter to the Department of Public Works, that the conservation would cost $1,500 but the funds were never acquired. In 1968, after Martin Luther King Jr.'s death, Alston was asked to create another mural for the hospital to be placed in a pavilion named after the assassinated civil rights leader titled Man Emerging from the Darkness of Poverty and Ignorance into the Light of a Better World. One year after Alston's death in 1977, a group of artists and historians, including the renowned Painter and collagist Romare Bearden and art Historian Greta Berman, together with administrators from the hospital, and from the NYC Art Commission, examined the murals, and presented a proposal for their restoration to then-mayor Ed Koch. The request was approved, and conservator Alan Farancz set to work in 1979, rescuing the murals from further decay. Many years passed, and the murals began to deteriorate again – especially the Alston works, which continued to suffer effects from the radiators. In 1991 the Municipal Art Society's Adopt-a-Mural program was launched and the Harlem Hospital murals were chosen for further restoration (Greta Berman. Personal experience). A grant from Alston's sister Rousmaniere Wilson and step-sister Aida Bearden Winters assisted in completing a restoration of the works in 1993. In 2005 Harlem Hospital announced a $2 million project to conserve Alston's murals and three other pieces in the original commissioned project as part of a $225 million hospital expansion.

The civil rights movement of the 1960s was a major influence on Alston. Considered to be one of his most powerful and impressive periods in the late 1950s he began working in black and white up until the mid-1960s. Some of the works are simple abstracts of black ink on white paper, similar to a Rorschach test. Untitled (c. 1960s) shows a boxing match in great simplicity with an attempt to express the drama of the fight through few brushstrokes. Alston worked with oil-on-Masonite during this period as well, utilizing impasto, cream and ochre to create a moody cave-like artwork. Black and White #1 (1959) is one of Alston's more "monumental" works. Gray, white and black come together to fight for space on an abstract canvas, in a softer form than the more harsh Franz Kline. Alston continued to explore the relationship between monochromatic hues throughout the series which Wardlaw describes as "some of the most profoundly beautiful works of twentieth-century American art."

In 1963, Alston co-founded Spiral with Romare Bearden and Hale Woodruff. Spiral served as a collective of conversation and artistic exploration for a large group of artists who "addressed how black artists should relate to American society in a time of segregation." Artists and arts supporters gathered for Spiral, such as Emma Amos, Perry Ferguson and Merton Simpson. This group served as the 1960s version of 306. Alston was described as an "intellectual activist", and in 1968 he spoke at Columbia about his activism. In the mid-1960s Spiral created an exhibition of black and white artworks, but the exhibition was never officially sponsored by the group due to inner-group disagreements.

In 1968, Alston received a presidential appointment from Lyndon Johnson to the National Council of Culture and the Arts. Mayor John Lindsay appointed him to the New York City Art Commission in 1969. He was made full professor at City College of New York in 1973 where he had taught since 1968. In 1975 he was awarded the first Distinguished Alumni Award from Teachers College. The Art Student's League created a 21-year merit scholarship in 1977 under Alston's name to commemorate each year of his tenure.

In January 1977 Myra Logan died. Months later on April 27, 1977, Charles Spinky Alston died after a long bout with cancer. His memorial Service was held at St. Martins Episcopal Church on May 21, 1977, in New York City.

While obtaining his master's degree, Alston was the boys’ work Director at the Utopia Children's House, started by James Lesesne Wells. He also began teaching at the Harlem Community Art Center, founded by Augusta Savage in the basement of what is now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Alston's teaching style was influenced by the work of John Dewey, Arthur Wesley Dow, and Thomas Munro. During this period, Alston began to teach the 10-year-old Jacob Lawrence, whom he strongly influenced. Alston was introduced to African art by the poet Alain Locke. In the late 1920s Alston joined Bearden and other black artists who refused to exhibit in william E. Harmon Foundation shows, which featured all-black artists in their traveling exhibits. Alston and his friends thought the exhibits were curated for a white audience, a form of segregation which the men protested. They did not want to be set aside but exhibited on the same level as art peers of every skin color.