| Who is it? | Music Department, Soundtrack, Composer |

| Birth Day | June 29, 1911 |

| Birth Place | New York City, New York, United States |

| Age | 109 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | December 24, 1975(1975-12-24) (aged 64)\nLos Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Resting place | Beth David Cemetery Elmont, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | Bernard Maximillian Herrmann |

| Occupation | Composer, conductor |

| Years active | 1941–1975 |

| Spouse(s) | Lucille Fletcher (m. 1939; div. 1948) Lucy Anderson (m. 1949; div. 1964) Norma Shepherd (m. 1967) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | 1941 Academy Award for Music Score of a Dramatic Picture, The Devil and Daniel Webster a.k.a. All That Money Can Buy 1976 BAFTA Award for Best Film Music, Taxi Driver |

| Website | thebernardherrmannestate.com |

Bernard Herrmann, a highly acclaimed Music Department, Soundtrack, and Composer in the United States, is projected to have a net worth ranging between $100K to $1M by the year 2025. Herrmann's unparalleled talent and extensive contribution to the music industry have undoubtedly positioned him as one of the most influential figures in his field. With his extraordinary compositions and remarkable expertise, it comes as no surprise that his net worth is estimated to reach such impressive heights. Throughout his illustrious career, Herrmann has left an indelible mark on the world of music, creating iconic soundtracks and captivating audiences with his brilliance.

I have the final say, or I don’t do the music. The reason for insisting on this is simply, compared to Orson Welles, a man of great musical culture, most other directors are just babes in the woods. If you were to follow their taste, the music would be awful. There are exceptions. I once did a film The Devil and Daniel Webster with a wonderful director William Dieterle. He was also a man of great musical culture. And Hitchcock, you know, is very sensitive; he leaves me alone. It depends on the person. But if I have to take what a director says, I’d rather not do the film. I find it’s impossible to work that way.

Herrmann was an early and enthusiastic proponent of the music of Charles Ives. He met Ives in the early 1930s, performed many of his works while Conductor of the CBS Symphony Orchestra, and conducted Ives' Second Symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra on his first visit to London in 1956. Herrmann later made a recording of the work in 1972 and this reunion with the LSO, after more than a decade, was significant to him for several reasons - he had long hoped to record his own interpretation of the symphony, feeling that Leonard Bernstein's 1951 version was "overblown and inaccurate"; on a personal level, it also served to assuage Herrmann's long-held feeling that he had been snubbed by the orchestra after his first visit in 1956. The notoriously prickly Composer had also been enraged by the recent appointment of the LSO's new chief Conductor André Previn, who Herrmann detested, and deprecatingly referred to as "that jazz boy".

In 1934, he joined the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) as a staff Conductor. Within two years he was appointed music Director of the Columbia Workshop, an experimental radio drama series for which Herrmann composed or arranged music (one notable program was The Fall of the City). Within nine years, he had become Chief Conductor to the CBS Symphony Orchestra. He was responsible for introducing more new works to US audiences than any other conductor — he was a particular champion of Charles Ives' music, which was virtually unknown at that time. Herrmann's radio programs of concert music, which were broadcast under such titles as Invitation to Music and Exploring Music, were planned in an unconventional way and featured rarely heard music, old and new, which was not heard in public concert halls. Examples include broadcasts devoted to music of famous amateurs or of notable royal personages, such as the music of Frederick the Great of Prussia, Henry VIII, Charles I, Louis XIII and so on.

These works are for narrator and full orchestra, intended to be broadcast over the radio (since a human voice would not be able to be heard over the full volume of an orchestra). In a 1938 broadcast of the Columbia Workshop, Herrmann distinguished "melodrama" from "melodram" and explained that these works are not part of the former, but the latter. The 1935 works were composed before June 1935.

In 1934, Herrmann met a young CBS secretary and aspiring Writer, Lucille Fletcher. Fletcher was impressed with Herrmann's work, and the two began a five-year courtship. Marriage was delayed by the objections of Fletcher's parents, who disliked the fact that Herrmann was a Jew and were put off by what they viewed as his abrasive personality. The couple finally married on October 2, 1939. They had two daughters: Dorothy (born 1941) and Wendy (born 1945). Fletcher was to become a noted radio scriptwriter, and she and Herrmann collaborated on several projects throughout their career. He contributed the score to the famed 1941 radio presentation of Fletcher's original story, The Hitch-Hiker, on the Orson Welles Show; and Fletcher helped to write the libretto for his operatic adaptation of Wuthering Heights. The couple divorced in 1948. The next year he married Lucille's cousin, Lucy (Kathy Lucille) Anderson. That marriage lasted 16 years, until 1964.

Herrmann's many US broadcast premieres during the 1940s included Myaskovsky's 22nd Symphony, Gian Francesco Malipiero's 3rd Symphony, Richard Arnell's 1st Symphony, Edmund Rubbra's 3rd Symphony and Ives' 3rd Symphony. He performed the works of Hermann Goetz, Alexander Gretchaninov, Niels Gade and Franz Liszt, and received many outstanding American musical awards and grants for his unusual programming and championship of little-known composers. In Dictators of the Baton, David Ewen wrote that Herrmann was "one of the most invigorating influences in the radio music of the past decade." Also during the 1940s, Herrmann's own concert music was taken up and played by such celebrated maestri as Leopold Stokowski, Sir John Barbirolli, Sir Thomas Beecham and Eugene Ormandy.

As well as his many film scores, Herrmann wrote several concert pieces, including his Symphony in 1941; the opera Wuthering Heights; the cantata Moby Dick (1938), dedicated to Charles Ives; and For the Fallen, a tribute to the Soldiers who died in battle in World War II, among others. He recorded all these compositions, and several others, for the Unicorn label during his last years in London. A work written late in his life, Souvenir de Voyages, showed his ability to write non-programmatic pieces.

Pristine Audio has released two CDs of Herrmann's radio broadcasts. One is devoted to a CBS programme from 1945 that features music by Handel, Vaughan Williams and Elgar; the other is devoted to works by Charles Ives, Robert Russell Bennett and Herrmann himself.

From the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, Herrmann scored a series of notable mythically-themed fantasy films, including Journey to the Center of the Earth and the Ray Harryhausen Dynamation epics The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Jason and the Argonauts, Mysterious Island and The Three Worlds of Gulliver. His score for The 7th Voyage was particularly highly acclaimed by admirers of that genre of film and was praised by Harryhausen as Herrmann's best score of the four.

Herrmann's involvement with electronic musical instruments dates back to 1951, when he used the theremin in The Day the Earth Stood Still. Robert B. Sexton has noted that this score involved the use of treble and bass theremins (played by Dr. Samuel Hoffmann and Paul Shure), electric strings, bass, prepared piano, and guitar together with various pianos and harps, electronic organs, brass, and percussion, and that Herrmann treated the theremins as a truly orchestral section.

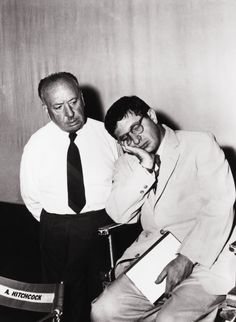

Herrmann is closely associated with the Director Alfred Hitchcock. He wrote the scores for seven Hitchcock films, from The Trouble with Harry (1955) to Marnie (1964), a period that included Vertigo, North by North West, and Psycho. He also was credited as sound consultant on The Birds (1963), as there was no actual music in the film as such, only electronically made bird sounds.

The film score for the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) was composed by Herrmann, but two of the most significant pieces of music in the film — the song, "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be)", and the Storm Clouds Cantata played in the Royal Albert Hall — are not by Herrmann (although he did re-orchestrate the cantata by Australian-born Composer Arthur Benjamin written for the earlier Hitchcock film of the same name). However, this film did give Herrmann the opportunity for an on-screen appearance: he is the Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra in the Albert Hall scene.

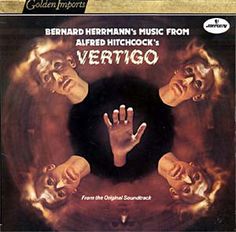

His score for Vertigo (1958) is seen as just as masterful. In many of the key scenes Hitchcock let Herrmann's score take center stage, a score whose melodies, echoing the "Liebestod" from Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde, dramatically convey the main character's obsessive love for the woman he tries to shape into a long-dead, past love.

Herrmann was also an ardent champion of the romantic-era Composer Joachim Raff, whose music had fallen into near-oblivion by the 1960s. During the 1940s, Herrmann had played Raff's 3rd and 5th Symphonies in his CBS radio broadcasts. In May 1970, Herrmann conducted the world premiere recording of Raff's Fifth Symphony Lenore for the Unicorn label, which he mainly financed himself. The recording did not attract much notice in its time, despite receiving excellent reviews, but is now considered a major turning-point in the rehabilitation of Raff as a Composer.

Elmer Bernstein adapted and arranged Herrmann's original score from J. Lee Thompson's Cape Fear (1962), and used it for the 1991 Martin Scorsese remake. After Bernstein realized there was not enough music in the score from the original film, he added sections from Herrmann's unused score for Hitchcock's Torn Curtain, including the music composed for the murder of the character "Gromek". The score for Cape Fear evokes both the gathering clouds of the destructive hurricane and the murderous intent of killer Max Cady. Bernstein also recorded Herrmann's score for The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, which was released in 1975 on the Varese Sarabande label later reissued on CD in the 1990s.

In 1963 Herrmann began writing original music for the CBS-TV anthology series, The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, which was in its eighth season. Hitchcock himself served only as advisor on the show, which he hosted, but Herrmann was again working with former Mercury Theatre actor Norman Lloyd, co-producer (with Joan Harrison) of the series. Herrmann scored 17 episodes (1963–1965) and, like much of his work for CBS, the music was frequently reused for other programs.

During his last years in England, between 1966 and 1975, Herrmann made several LPs of other composers' music for assorted record labels. These included Phase 4 Stereo recordings of Gustav Holst's The Planets and Charles Ives's 2nd Symphony, as well as an album entitled "The Impressionists" (music by Satie, Debussy, Ravel, Fauré and Honegger) and another entitled "The Four Faces of Jazz" (works by Weill, Gershwin, Stravinsky and Milhaud). As well as recording his own film music in Phase 4 Stereo he made LPs of movie scores by others, such as "Great Shakespearean Films" (music by Shostakovich for Hamlet, Walton for Richard III and Rózsa for Julius Caesar), and "Great British Film Music" (movie scores by Lambert, Bax, Benjamin, Walton, Vaughan Williams, and Bliss).

By 1967 Herrmann worked almost exclusively in England. In November 1967, the 56-year-old Composer married 27-year-old Journalist Norma Shepherd, his third wife. In August 1971 the Herrmanns made London their permanent home.

His music continues to be used in films and recordings after his death. "Georgie's Theme" from Herrmann's score for the 1968 film Twisted Nerve is whistled by one-eyed nurse Elle Driver in the hospital corridor scene in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill: Volume 1 (2003). The opening theme from Vertigo was used in the prologue to Lady Gaga's "Born This Way" video, and during a flashback sequence in the pilot episode of FX's American Horror Story, which also featured "Georgie's Theme" in later episodes as a recurring musical motif for the character of Tate. Vertigo's opening sequence was also copied for the opening sequence of the 1993 miniseries, "Tales Of The City", an adaptation of a series of books by Armistead Maupin. Fellow film Composer Danny Elfman adapted Herrmann's music for Psycho for use in Director Gus Van Sant's 1998 remake and borrowed from Herrmann's "Mountaintop/Sunrise" theme, from Journey to the Center of the Earth, for his main Batman theme. On its 1977 album Ra, American progressive rock group Utopia also adapted "Mountaintop/Sunrise," in a rock arrangement, as the introduction to the album's opening song, "Communion With The Sun." And most recently, Ludovic Bource used the love theme from Vertigo literally in the last reels of 2011's The Artist.

Herrmann was among those who rebutted the charges Pauline Kael made in her 1971 essay "Raising Kane", in which she revived controversy over the authorship of the screenplay for Citizen Kane and denigrated Welles's contributions.

In a question-and-answer session at George Eastman House in October 1973, Herrmann stated that, unlike most film composers who did not have any creative input into the style and tone of the score, he insisted on creative control as a condition of accepting a scoring assignment:

Charles Gerhardt conducted a 1974 RCA recording entitled "The Classic Film Scores of Bernard Herrmann" with the National Philharmonic Orchestra. It featured Suites from Citizen Kane (with Kiri Te Kanawa singing Salammbo's Aria) and White Witch Doctor, along with music from On Dangerous Ground, Beneath the 12-Mile Reef, and the Hangover Square Piano Concerto.

Herrmann is still a prominent figure in the world of film music today, despite his death in 1975. As such, his career has been studied extensively by biographers and documentarians. His string-only score for Psycho, for Example, set the standard when it became a new way to write music for thrillers (rather than big fully orchestrated pieces). In 1992 a documentary, Music for the Movies: Bernard Herrmann, was made about him. Also in 1992 a 2½-hour-long National Public Radio documentary was produced on his life — Bernard Herrmann: a Celebration of his Life and Music (Bruce A. Crawford). In 1991, Steven C. Smith wrote a Herrmann biography titled A Heart at Fire's Center, a quotation from a favorite Stephen Spender poem of Herrmann's.

Sir George Martin, best known for producing and often adding orchestration to The Beatles music, cites Herrmann as an influence in his own work, particularly in Martin's scoring of the Beatles' song "Eleanor Rigby". Martin later expanded on this as an extended suite for McCartney's 1984 film Give My Regards to Broad Street, which features a very recognizable hommage to Herrmann's score for Psycho.

Fellow composers Richard Band, Graeme Revell, Christopher Young, Danny Elfman and Brian Tyler consider Herrmann to be a major inspiration. In 1985, Richard Band's opening theme to Re-Animator borrows heavily from Herrmann's opening score to Psycho. In 1990, Graeme Revell had adapted Herrmann's music from Psycho for its television sequel-prequel Psycho IV: The Beginning. Revell's early orchestral music during the early nineties, such as Child's Play 2 (which its music score being a reminiscent of Herrmann's scores to the 1973 film Sisters, due to the synthesizers incorporated in the chilling parts of the orchestral score) as well as the 1963 The Twilight Zone episode "Living Doll" (which inspired the Child's Play franchise), were very similar to Herrmann's work. Also, Revell's score for the video game Call of Duty 2 was very much a reminiscent of Herrmann's very rare WWII music scores such as The Naked and the Dead and Battle of Neretva. Young, who was a jazz Drummer at first, listened to Herrmann's works which convinced him to be a film Composer. Elfman has said he first became interested in film music upon seeing The Day the Earth Stood Still, and he paid homage to that score in his music for Mars Attacks! Tyler's score for Bill Paxton's film Frailty was greatly influenced by Herrmann's film music.

In 1996, Sony Classical released a recording of Herrmann's music, The Film Scores, performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic under the baton of Esa-Pekka Salonen. This disc received the 1998 Cannes Classical Music Award for "Best 20th-Century Orchestral Recording." It was also nominated for the 1998 Grammy Award for "Best Engineered Album, Classical." In 2004 Sony Classical re-released this superb recording at a budget price in its "Great Performances" series (SNYC 92767SK).

According to McGilligan, Herrmann later tried to reconcile with Hitchcock, but Hitchcock refused to see him. Herrmann's widow Norma Herrmann disputed this in a conversation with Günther Kögebehn for the Bernard Herrmann Society in 2004:

In 2005 the American Film Institute respectively ranked Herrmann's scores for Psycho and Vertigo #4 and #12 on their list of the 25 greatest film scores. His scores for the following films were also nominated for the list:

"This is rather interesting, because it comes a year after Hitchcock had abruptly fired Herrmann from his work scoring Torn Curtain and indicates Hitchcock may have hoped to mend fences with Herrmann and have him score his next film, Topaz," reported Wellesnet, the Orson Welles website, in April 2009:

Herrmann, the son of a Jewish middle-class family of Russian origin, was born in New York City as Max Herman. His father, Abram Dardik, was from Ukraine and had changed the family name. Herrmann attended high school at DeWitt Clinton High School, an all-boys public school at that time on 10th Avenue and 59th Street in New York City. His father encouraged music activity, taking him to the opera, and encouraging him to learn the violin. After winning a composition prize at the age of thirteen, he decided to concentrate on music, and went to New York University, where he studied with Percy Grainger and Philip James. He also studied at the Juilliard School and, at the age of twenty, formed his own orchestra, the New Chamber Orchestra of New York.

During the same period, Herrmann turned his talents to writing scores for television shows. He wrote the scores for several well-known episodes of the original Twilight Zone series, including the lesser known theme used during the series' first season, as well as the opening theme to Have Gun–Will Travel.

Decca reissued on CD a series of Phase 4 Stereo recordings with Herrmann conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra, mostly in excerpts from his various film scores, including one devoted to music from several of the Hitchcock films (including Psycho, Marnie and Vertigo). In the liner notes of the Hitchcock Phase 4 album, Herrmann said that the suite from The Trouble with Harry was a "portrait of Hitch". Another album was devoted to his fantasy film scores — a few of them being the films of the special effects Animator Ray Harryhausen, including music from The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad and The Three Worlds of Gulliver. His other Phase 4 Stereo LPs of the 1970s included Music from the Great Film Classics (suites and excerpts from Jane Eyre, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Citizen Kane and The Devil and Daniel Webster); and "The Fantasy World of Bernard Herrmann" (Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Day the Earth Stood Still, and Fahrenheit 451.)

Early in his life, Herrmann committed himself to a creed of personal integrity at the price of unpopularity: the quintessential Artist. His philosophy is summarized by a favorite Tolstoy quote: ‘Eagles fly alone and sparrows fly in flocks.' Thus, Herrmann would only compose music for films when he was allowed the artistic liberty to compose what he wished without the Director getting in the way: the cause of the split with Hitchcock after over a decade of composing scores for the director's films.

Herrmann was a sound consultant on The Birds, which made extensive use of an electronic instrument called the mixturtrautonium, although the instrument was performed by Oskar Sala on the film’s Soundtrack. Herrmann used several electronic instruments on his score of It’s Alive, as well as the Moog synthesizer for the main themes in Endless Night and Sisters.