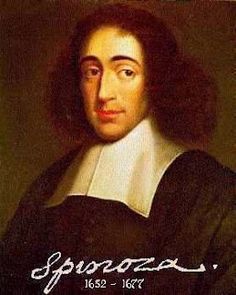

| Who is it? | Dutch philosopher |

| Birth Day | November 24, 1632 |

| Birth Place | Amsterdam, Dutch Republic, Dutch |

| Age | 387 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 21 February 1677(1677-02-21) (aged 44)\nThe Hague, Dutch Republic |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Residence | Netherlands |

| Education | Talmud Torah of Amsterdam (withdrew) |

| Alma mater | University of Leiden (no degree) |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Rationalism, founder of Spinozism |

| Main interests | Ethics, epistemology, metaphysics, Hebrew grammar |

| Notable ideas | Pantheism, determinism, neutral monism, parallelism, intellectual and religious freedom, separation of church and state, criticism of Mosaic authorship of some books of the Hebrew Bible, political society as derived from power (not contract), affect, natura naturans/natura naturata |

Baruch Spinoza, a renowned Dutch philosopher, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in the year 2025. Known for his profound contributions to philosophy, Spinoza's work continues to shape contemporary thought. Born in Amsterdam in the 17th century, he challenged traditional religious and political institutions with his rationalist ideas. Spinoza's philosophical concepts, such as his pantheistic view of God and his ethical theories, have had a lasting impact on various fields, including metaphysics, ethics, and political philosophy. Despite living a modest life as a lens grinder, his intellectual legacy has solidified him as one of the most influential philosophers in Dutch history.

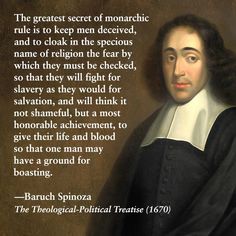

The Lords of the ma'amad, having long known of the evil opinions and acts of Baruch de Espinoza, have endeavoured by various means and promises, to turn him from his evil ways. But having failed to make him mend his wicked ways, and, on the contrary, daily receiving more and more serious information about the abominable heresies which he practised and taught and about his monstrous deeds, and having for this numerous trustworthy witnesses who have deposed and borne witness to this effect in the presence of the said Espinoza, they became convinced of the truth of the matter; and after all of this has been investigated in the presence of the honourable chachamin [sages], they have decided, with their consent, that the said Espinoza should be excommunicated and expelled from the people of Israel. By the decree of the angels, and by the command of the holy men, we excommunicate, expel, curse and damn Baruch de Espinoza, with the consent of God, Blessed be He, and with the consent of all the Holy Congregation, in front of these holy Scrolls with the six-hundred-and-thirteen precepts which are written therein, with the excommunication with which Joshua banned Jericho, with the curse with which Elisha cursed the boys and with all the curses which are written in the Book of the Law. Cursed be he by day and cursed be he by night; cursed be he when he lies down, and cursed be he when he rises up; cursed be he when he goes out, and cursed be he when he comes in. The Lord will not spare him; the anger and wrath of the Lord will rage against this man, and bring upon him all the curses which are written in this book, and the Lord will blot out his name from under heaven, and the Lord will separate him to his injury from all the tribes of Israel with all the curses of the covenant, which are written in the Book of the Law. But you who cleave unto the Lord God are all alive this day. We order that no one should communicate with him orally or in writing, or show him any favour, or stay with him under the same roof, or within four ells of him, or read anything composed or written by him.

Spinoza's ancestors were of Sephardic Jewish descent and were a part of the community of Portuguese Jews that had settled in the city of Amsterdam in the wake of the Portuguese Inquisition (1536), which had resulted in forced conversions and expulsions from the Iberian peninsula.

Attracted by the Decree of Toleration issued in 1579 by the Union of Utrecht, Portuguese "conversos" first sailed to Amsterdam in 1593 and promptly reconverted to Judaism. In 1598 permission was granted to build a synagogue, and in 1615 an ordinance for the admission and government of the Jews was passed. As a community of exiles, the Portuguese Jews of Amsterdam were highly proud of their identity.

Spinoza's father was born roughly a century after this forced conversion in the small Portuguese city of Vidigueira, near Beja in Alentejo. When Spinoza's father was still a child, Spinoza's grandfather, Isaac de Spinoza, who was from Lisbon, took his family to Nantes in France. They were expelled in 1615 and moved to Rotterdam, where Isaac died in 1627.

Second, the Amsterdam Jewish community was largely composed of former "conversos" who had fled from the Portuguese Inquisition within the previous century, with their children and grandchildren. This community must have been concerned to protect its reputation from any association with Spinoza lest his controversial views provide the basis for their own possible persecution or expulsion. There is little evidence that the Amsterdam municipal authorities were directly involved in Spinoza's censure itself. But "in 1619, the town council expressly ordered [the Portuguese Jewish community] to regulate their conduct and ensure that the members of the community kept to a strict observance of Jewish law." Other evidence makes it clear that the danger of upsetting the civil authorities was never far from mind, such as bans adopted by the synagogue on public wedding or funeral processions and on discussing religious matters with Christians, lest such activity might "disturb the liberty we enjoy." Thus, the issuance of Spinoza's censure was almost certainly, in part, an exercise in self-censorship by the Portuguese Jewish community in Amsterdam.

Benedito de Espinoza was born on 24 November 1632 in the Jodenbuurt in Amsterdam, Netherlands. He was the second son of Miguel de Espinoza, a successful, although not wealthy, Portuguese Sephardic Jewish merchant in Amsterdam. His mother, Ana Débora, Miguel's second wife, died when Baruch was only six years old. Spinoza's mother tongue was Portuguese, although he also knew Hebrew, Spanish, Dutch, perhaps French, and later Latin. Although he wrote in Latin, Spinoza learned the language only late in his youth.

Spinoza adopted the Latin name Benedictus de Spinoza, began boarding with Van den Enden, and began teaching in his school. Following an anecdote in an early biography by Johannes Colerus, he is said to have fallen in love with his teacher's daughter, Clara, but she rejected him for a richer student. (This story has been discounted on the basis that Clara Maria van den Enden was born in 1643 and would have been no more than about 18 years old when Spinoza left Amsterdam. In 1671 she married Dirck Kerckring.)

Leo Strauss dedicated his first book, Spinoza's Critique of Religion, to an examination of the latter's ideas. In the book, Strauss identified Spinoza as part of the tradition of Enlightenment rationalism that eventually produced Modernity. Moreover, he identifies Spinoza and his works as the beginning of Jewish Modernity. More recently Jonathan Israel argued that, from 1650 to 1750, Spinoza was "the chief challenger of the fundamentals of revealed religion, received ideas, tradition, morality, and what was everywhere regarded, in absolutist and non-absolutist states alike, as divinely constituted political authority."

In 1653, at age 20, Spinoza began studying Latin with Francis van den Enden (Franciscus van den Enden), a notorious free thinker, former Jesuit, and radical democrat who likely introduced Spinoza to scholastic and modern philosophy, including that of Descartes. (A decade later, in the early 1660s, Van den Enden was considered to be a Cartesian and atheist, and his books were put on the Catholic Index of Banned Books.)

After his father's death in 1654, Spinoza and his younger brother Gabriel (Abraham) ran the family importing Business. The Business ran into serious financial difficulties, however, perhaps as a result of the First Anglo-Dutch War. In March 1656, Spinoza filed suit with the Amsterdam municipal authorities to be declared an orphan in order to escape his father's Business debts and so that he could inherit his mother's estate (which at first was incorporated into his father's estate) without it being subject to his father's creditors. In addition, after having made substantial contributions to the Talmud Torah synagogue in 1654 and 1655, he reduced his December 1655 contribution and his March 1656 pledge to nominal amounts (and the March 1656 pledge was never paid).

Third, it appears likely that Spinoza had already taken the initiative to separate himself from the Talmud Torah congregation and was vocally expressing his hostility to Judaism itself. He had probably stopped attending services at the synagogue, either after the lawsuit with his sister or after the knife attack on its steps. He might already have been voicing the view expressed later in his Theological-Political Treatise that the civil authorities should suppress Judaism as harmful to the Jews themselves. Either for financial or other reasons, he had in any case effectively stopped contributing to the synagogue by March 1656. He had also committed the "monstrous deed," contrary to the regulations of the synagogue and the views of some rabbinical authorities (including Maimonides), of filing suit in a civil court rather than with the synagogue authorities—to renounce his father's heritage, no less. Upon being notified of the issuance of the censure, he is reported to have said: "Very well; this does not force me to do anything that I would not have done of my own accord, had I not been afraid of a scandal." Thus, unlike most of the censure issued routinely by the Amsterdam congregation to discipline its members, the censure issued against Spinoza did not lead to repentance and so was never withdrawn.

Spinoza moved around 1660 or 1661 from Amsterdam to Rijnsburg (near Leiden), the headquarters of the Collegiants. In Rijnsburg, he began work on his Descartes' "Principles of Philosophy" as well as on his masterpiece, the Ethics. In 1663, he returned briefly to Amsterdam, where he finished and published Descartes' "Principles of Philosophy," the only work published in his lifetime under his own name, and then moved the same year to Voorburg.

The writings of René Descartes have been described as "Spinoza's starting point." Spinoza's first publication was his geometric exposition (proofs using the geometric method on the model of Euclid with definitions, axioms, etc.) of Descartes's Parts I and II of Principles of Philosophy (1663). Spinoza has been associated with Leibniz and Descartes as "rationalists" in contrast to "empiricists."

Spinoza engaged in correspondence from December 1664 to June 1665 with Willem van Blijenbergh, an amateur Calvinist theologian, who questioned Spinoza on the definition of evil. Later in 1665, Spinoza notified Oldenburg that he had started to work on a new book, the Theologico-Political Treatise, published in 1670. Leibniz disagreed harshly with Spinoza in his own manuscript "Refutation of Spinoza," but he is also known to have met with Spinoza on at least one occasion (as mentioned above), and his own work bears some striking resemblances to specific important parts of Spinoza's philosophy (see: Monadology).

Spinoza also corresponded with Peter Serrarius, a radical Protestant and millennarian merchant. Serrarius was a patron to Spinoza after Spinoza left the Jewish community and even had letters sent and received for the Philosopher to and from third parties. Spinoza and Serrarius maintained their relationship until Serrarius' death in 1669. By the beginning of the 1660s, Spinoza's name became more widely known, and eventually Gottfried Leibniz and Henry Oldenburg paid him visits, as stated in Matthew Stewart's The Courtier and the Heretic. Spinoza corresponded with Oldenburg for the rest of his short life.

In 1670, Spinoza moved to The Hague where he lived on a small pension from Jan de Witt and a small annuity from the brother of his dead friend, Simon de Vries. He worked on the Ethics, wrote an unfinished Hebrew grammar, began his Political Treatise, wrote two scientific essays ("On the Rainbow" and "On the Calculation of Chances"), and began a Dutch translation of the Bible (which he later destroyed).

In 1676, Spinoza met with Leibniz at The Hague for a discussion of his principal philosophical work, Ethics, which had been completed in 1676. This meeting was described in Matthew Stewart's The Courtier and the Heretic.

Spinoza's health began to fail in 1676, and he died on 21 February 1677 at the age of 44. His premature death was said to be due to lung illness, possibly silicosis as a result of breathing in glass dust from the lenses that he ground. Later, a shrine was made of his home in The Hague.

Spinoza earned a modest living from lens-grinding and instrument making, yet he was involved in important optical investigations of the day while living in Voorburg, through correspondence and friendships with scientist Christiaan Huygens and Mathematician Johannes Hudde, including debate over microscope design with Huygens, favouring small objectives and collaborating on calculations for a prospective 40 ft telescope which would have been one of the largest in Europe at the time. The quality of Spinoza's lenses was much praised by Christiaan Huygens, among others. In fact, his technique and instruments were so esteemed that Constantijn Huygens ground a "clear and bright" 42 ft. telescope lens in 1687 from one of Spinoza's grinding dishes, ten years after his death. The exact type of lenses that Spinoza made are not known, but very likely included lenses for both the microscope and telescope. He was said by Anatomist Theodor Kerckring to have produced an "excellent" microscope, the quality of which was the foundation of Kerckring's anatomy claims. During his time as a lens and instrument maker, he was also supported by small but regular donations from close friends.

Spinoza's "God or Nature" (Deus sive Natura) provided a living, natural God, in contrast to Isaac Newton's first cause argument and the dead mechanism of Julien Offray de La Mettrie's (1709–1751) work, Man a Machine (L'homme machine). Coleridge and Shelley saw in Spinoza's philosophy a religion of nature. Novalis called him the "God-intoxicated man". Spinoza inspired the poet Shelley to write his essay "The Necessity of Atheism".

In 1785, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi published a condemnation of Spinoza's pantheism, after Gotthold Lessing was thought to have confessed on his deathbed to being a "Spinozist", which was the equivalent in his time of being called an atheist. Jacobi claimed that Spinoza's doctrine was pure materialism, because all Nature and God are said to be nothing but extended substance. This, for Jacobi, was the result of Enlightenment rationalism and it would finally end in absolute atheism. Moses Mendelssohn disagreed with Jacobi, saying that there is no actual difference between theism and pantheism. The issue became a major intellectual and religious concern for European civilization at the time.

By 1879, Spinoza’s pantheism was praised by many, but was considered by some to be alarming and dangerously inimical.

According to German Philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), when Spinoza wrote in Deus sive Natura (Latin for 'God or Nature'), Spinoza meant God was natura naturans (nature doing what nature does; literally, 'nature naturing'), not natura naturata (nature already created; literally, 'nature natured'). Jaspers believed that Spinoza, in his philosophical system, did not mean to say that God and Nature are interchangeable terms, but rather that God's transcendence was attested by his infinitely many attributes, and that two attributes known by humans, namely Thought and Extension, signified God's immanence. Even God under the attributes of thought and extension cannot be identified strictly with our world. That world is of course "divisible"; it has parts. But Spinoza said, "no attribute of a substance can be truly conceived from which it follows that the substance can be divided", meaning that one cannot conceive an attribute in a way that leads to division of substance. He also said, "a substance which is absolutely infinite is indivisible" (Ethics, Part I, Propositions 12 and 13). Following this logic, our world should be considered as a mode under two attributes of thought and extension. Therefore, according to Jaspers, the pantheist formula "One and All" would apply to Spinoza only if the "One" preserves its transcendence and the "All" were not interpreted as the totality of finite things.

Martial Guéroult (1891–1976) suggested the term "panentheism", rather than "pantheism" to describe Spinoza's view of the relation between God and the world. The world is not God, but it is, in a strong sense, "in" God. Not only do finite things have God as their cause; they cannot be conceived without God. However, American panentheist Philosopher Charles Hartshorne (1897–2000) insisted on the term Classical Pantheism to describe Spinoza's view.

In the final part of the "Ethics", his concern with the meaning of "true blessedness", and his explanation of how emotions must be detached from external causes in order to master them, foreshadow psychological techniques developed in the 1900s. His concept of three types of knowledge—opinion, reason, intuition—and his assertion that intuitive knowledge provides the greatest satisfaction of mind, lead to his proposition that the more we are conscious of ourselves and Nature/Universe, the more perfect and blessed we are (in reality) and that only intuitive knowledge is eternal.

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein evoked Spinoza with the title (suggested to him by G. E. Moore) of the English translation of his first definitive philosophical work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, an allusion to Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. Elsewhere, Wittgenstein deliberately borrowed the expression sub specie aeternitatis from Spinoza (Notebooks, 1914-16, p. 83). The structure of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus does have some structural affinities with Spinoza's Ethics (though, admittedly, not with the latter's own Tractatus) in erecting complex philosophical arguments upon basic logical assertions and principles. Furthermore, in propositions 6.4311 and 6.45 he alludes to a Spinozian understanding of eternity and interpretation of the religious concept of eternal life, stating that "If by eternity is understood not eternal temporal duration, but timelessness, then he lives eternally who lives in the present." (6.4311) "The contemplation of the world sub specie aeterni is its contemplation as a limited whole." (6.45)

When George Santayana graduated from college, he published an essay, "The Ethical Doctrine of Spinoza", in The Harvard Monthly. Later, he wrote an introduction to Spinoza's Ethics and "De intellectus emendatione". In 1932, Santayana was invited to present an essay (published as "Ultimate Religion") at a meeting at The Hague celebrating the tricentennial of Spinoza's birth. In Santayana's autobiography, he characterized Spinoza as his "master and model" in understanding the naturalistic basis of morality.

Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries grew even more interested in Spinoza, often from a left-wing or Marxist perspective. Karl Marx liked Spinoza's account of the universe, interpreting it as materialistic. The Philosophers Louis Althusser, Gilles Deleuze, Antonio Negri and Étienne Balibar have each drawn upon Spinoza's philosophy. Deleuze's doctoral thesis, published in 1968, calls him "the Prince of philosophers". Nietzsche esteemed few Philosophers, but he esteemed Spinoza. However, Nietzsche never read Spinoza's works themselves, but learned about Spinoza from Kuno Fischer's History of Modern Philosophy.

PBS television series, Jeeves and Wooster (1993) Season 4 Episode 2 has Spinoza as a central part of the plot. The series is based on the novels by P.G. Wodehouse and thus perhaps Spinoza also appears in one of them as well.

In September 2012, the Portugees-Israëlietische Gemeente te Amsterdam asked the chief rabbi of their community Haham Pinchas Toledano to reconsider the cherem after consulting several Spinoza experts. However he declined to remove it, citing Spinoza's "preposterous ideas, where he was tearing apart the very fundamentals of our religion".

Spinoza was considered to be an atheist because he used the word "God" (Deus) to signify a concept that was different from that of traditional Judeo–Christian monotheism. "Spinoza expressly denies personality and consciousness to God; he has neither intelligence, feeling, nor will; he does not act according to purpose, but everything follows necessarily from his nature, according to law...." Thus, Spinoza's cool, indifferent God is the antithesis to the concept of an anthropomorphic, fatherly God who cares about humanity.

Max Müller, in his lectures, noted the striking similarities between Vedanta and the system of Spinoza, saying "the Brahman, as conceived in the Upanishads and defined by Sankara, is clearly the same as Spinoza's 'Substantia'." Helena Blavatsky, a founder of the Theosophical Society also compared Spinoza's religious thought to Vedanta, writing in an unfinished essay "As to Spinoza's Deity—natura naturans—conceived in his attributes simply and alone; and the same Deity—as natura naturata or as conceived in the endless series of modifications or correlations, the direct out-flowing results from the properties of these attributes, it is the Vedantic Deity pure and simple."

Amsterdam and Rotterdam operated as important cosmopolitan centres where merchant ships from many parts of the world brought people of various customs and beliefs. This flourishing commercial activity encouraged a culture relatively tolerant of the play of new ideas, to a considerable degree sheltered from the censorious hand of ecclesiastical authority (though those considered to have gone "too far" might have gotten persecuted even in the Netherlands). Not by chance were the philosophical works of both Descartes and Spinoza developed in the cultural and intellectual background of the Dutch Republic in the 17th century. Spinoza may have had access to a circle of friends who were unconventional in terms of social tradition, including members of the Collegiants. One of the people he knew was Niels Stensen, a brilliant Danish student in Leiden; others included Albert Burgh, with whom Spinoza is known to have corresponded.

The attraction of Spinoza's philosophy to late 18th-century Europeans was that it provided an alternative to materialism, atheism, and deism. Three of Spinoza's ideas strongly appealed to them:

Similarities between Spinoza's philosophy and Eastern philosophical traditions have been discussed by many authors. The 19th-century German Sanskritist Theodor Goldstücker was one of the early figures to notice the similarities between Spinoza's religious conceptions and the Vedanta tradition of India, writing that Spinoza's thought was